On Christmas Eve, a child is born into the world. Not only that—a star rises. He is the star that lets people see the splendor of what is to come, that leads them to the glorified stable. He is the coming one, who heals human beings, so that they will heal one another. In his splendor, the world breathes peace. In his light, the world is given a new childhood.

And in that neighborhood there were shepherds in the field. They guarded and protected their flocks through the night. All at once, the angel of the Lord stood before them, and the light of the revelation of God shone about them. Great fear came upon them, but the angel said, ‘Have no fear. See, I proclaim a great joy to you, which shall be for all [humankind].’

Luke 2:8–101

The sky opens at Christmas. A splendor of light glorifies the darkness. A host of angels proclaim the most precious good: peace on Earth. “Have no fear,” said the angel of the Lord. “I proclaim a great joy to you.” A child is born to us in the middle of the night, a glorified night, a holy night.

What the angel proclaims, what the choirs of angels sing—the “Good News”—is one of the most familiar aspects of the Christmas festival. This familiarity has protected us from the enormity of what has been happening up through present times. And yet, we constantly struggle for a moment of silence, so we can stop and let a touch of joy expand within us, in the way children always ask when the first snow falls: Will it stick? Will it stay? Will it still be there when I wake up tomorrow?

When we seek for what brings us joy, we suffer from an overabundance of offerings, which are often merely a reflection of a self-induced emptiness. So, when does joy stick?

Nowadays, the sky is closed again. Or are we the ones who have not opened it? The time when the sky could open seems so near. In many songs, Gloria resounds as the triumph of a new dawn and echoes even where only the longing for a white Christmas remains. After a few days, it sounds like merely a tin pan, unable to resonate. The longing lost all resonance. The gold of the mother’s halo, the gold of the luminous bundle of straw upon which lies the newborn, naked and defenseless—all this is glumly reflected in the most unsightly objects of everyday life: glitter on wrapping paper, ribbons, and bows. But we forget to look up. Only children, as masters of anticipation, still know, for a short time, about the opening of the sky.

The Long Path of the Light’s Splendor

But why do we need to be protected at all? Why are the first words of the Angel of the Proclamation, “Have no fear”? What stirs up our fears? The sky and the heavens haven’t opened. But, actually, what is frightening is that they are always open.

“Gloria,” Doxa (δόξα in the original Greek), often translated as “Glory,” originally meant “splendor” of the glory. Splendor is not light. Splendor is an illumination that shines out of—or through—the opacity of matter.

If it condenses, it becomes a golden splendor, an aureole, a halo. It is the splendor worshiped by Zarathustra in Zamyad Yasht 19, the Persian “Hymn to the Earth,” as the one who will accompany the Saoshyant, the coming Savior. Speaking in the language of the Avesta (the Zoroastrian Scripture), he is called Khvarenah.

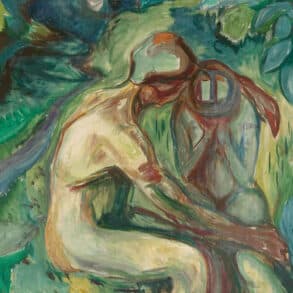

The opened heavens allow this splendor of light to descend to the Earth, to the point where it touches and penetrates it, to then rise up out of it, as splendor. The coming Savior will make the world “Frashokereti,” meaning “restored and healed.” “Frasha” (which we can still hear in the word “fresh”) means new, transfigured, glorified. In a glorified night, in this living primal, archetypal light, whose wellspring in paradise lies behind us, a child is born upon the Earth.

The Indologist Hermann Beckh translated this promise in the Avesta into his own, almost cultic language. “Sun-ether-aura” is how Beckh interpreted what appears in the original text of the Avesta as the “splendor of light” (Khvarenah) and later in the Gospel of Luke as “Doxa,” “Gloria.” Beckh calls this prophecy “probably one of the most tremendous prophecies that sounds to us out of the pre-Christian ages”:2

The mighty, the kingly Sun-ether-aura bearing prophecy, / the divinely-created one, / we venerate in prayer / which will pass over to the most victorious of saviors, / and to the others, his Apostles . . . .3

Thanks to this distance, it becomes possible to experience how long the path is that the splendor of the light has traveled until the birth of a child, who, one day, would carry the Savior. And how long the path will still be, which can be sensed in the distant future—the collective path to the Transfiguration of the Earth.

Great Fear Came upon Them

In the middle of the night, the heavens opened. The brightness of the Lord, “doxa Kyriou,” the splendor of the glory, has spread all around the shepherds, and great fear came upon them. Then the angel of the Lord says, “Have no fear!” But there is every reason to fear. For it is tremendous when heaven proclaims itself, and we see it open.

The sky and heavens are not this vault that unfolds on all sides like a star-endowed canopy, sheltering us and granting us a here-and-now on the Earth, like the gesture of the Madonna, draping herself in her cloak of humanity. We look to the heights, but what we see is the inner side of her cloak, the inner side of her gesture. We don’t look up to heaven.

Heaven is there where only creative powers reign unceasingly, without interruption. This is what is meant by the heights from which the choirs of angels sing.

And if we look thus far, we could become overwhelmed like Rilke when the sky “opened” for him in Duino Castle amidst the gale’s rage and roar coming from over the sea. The poet had just shouted at the order of the angels and already felt within himself the mightiness of their possible nearness: “And even if one should suddenly take me to its heart, I would expire from its greater presence.”4

The reality—yes, even the reality “here below”—when it proclaims itself to us by revealing its innermost being, it leaves us stunned. We tell ourselves that the heavens have opened, and we turn our gaze upwards. How could we look upwards, though, if we weren’t below? At the same time, we surmise that an even higher above, an even deeper below, eludes our view. We have the presentiment that they may be found within, the presentiment that we could break apart because of it.

“A ghostly silence enveloped us and forced us to stay silent”—so Walter Friedrich Otto described a trembling and, afterward, joyful experience during a hike in the forest with a friend.5 Their conversation touched on ancient myths and places, where deities and humans might unexpectedly meet. All of a sudden, they stopped, standing in the middle of the wilderness of the forest, as if by some prearranged signal, and they looked at one another. For a moment, the silence had spoken to them.

They had arrived at some place, the place of the “enormity of the primal origin.”

For what reaches beyond the order of angels is unknowable and inexpressible. This alone borders on the sphere of the enormity, on the sphere of the holy.

When it reveals itself within us, we are gripped by a hitherto unknown awe and, at the same time, a trembling. Deep silence is the only answer; it holds us upright, otherwise, we would “expire,” as in the words of Rilke. At the same time, the incomprehensible opens out in all its darkness. We just tremble and let silence prevail. Like the silence that can be heard immediately before birth, before every birth, be it a human child or the birth of something new within ourselves. A mighty night in us struggles with the overpowering daylight. In these moments, our hearts “expire,” and we can only kneel.

A Holy Night

And suddenly the fullness of the heavenly, angelic choirs was around the angel; their song of praise sounded forth to the Highest God, [the Ground of the World] . . . .

Luke 2:136

How is a night made holy? Is not every night holy? Christian Morgenstern calls the night a “Well of Stars” and feels himself flooded by its “joys of revelation” and asks, “Give to me what you know!”7 What does the night know? Isn’t Christmas made holy by the fact that the heavens seem closer to us?

The holy and that which by it is made holy belong to two different realms of existence. They are not one and the same. The many things that we call holy—a holy place, a holy person, a holy oath, a holy fealty, a holy temple, a holy cause, a holy angel—how different they are, though they have this in common with each other: They are all statements. The holy is assigned as an attribute to this or to that. Something is expressed about the temple, person, place, or fealty.

The enormity of “the holy” lies in the fact that it is not a thing that we can name. For what we mean by “holy” is not a statement, but rather the revelation of an effectivity, whose original source lies beyond all names, outside of all determination. So, nothing can be expressed about the holy. The holy can only be held silent within.

Like no other, Dionysius the Areopagite depicted the superessentiality of the divine, primal, original source. All that springs from the divine revelation is pure effectivity. Revelation and effectiveness have emerged from out of the holy, just as it has from out of its origin. The stream that flows from its source has, already at the first moment of flowing, moved away from the source. The water runs through a constantly changing environment at an ever-greater distance from its place, from its origin.

The origin is there, where the Gospel of Luke also speaks of the “Highest God,” the Ground of the World. The angels, each according to their task and their rank, the holy hierarchy, are they who participate in this activity. Their distance from the source determines their ordered rank; they can know themselves by it. “In my opinion, a hierarchy is a sacred order, a state of understanding, and an activity . . . .” 8 They go to-and-fro between the original source and the world of Earth and human beings. It is an uninterrupted dance, a receiving and passing on. Their being is their work. Hence, they sing. The choirs of angels sing to the divine ground of the world, the Higher God, the holy. They support, yes, they carry this world ground, similar to how they are depicted on early mosaics, for example, in Ravenna. They cause the holy to work between the heights and the depths. They receive it and give it on further, from holy rank to holy rank, until it reaches us in the depths. Their singing is our ability to remain silent within. And we will be healed.

Peace Will Be Born

God be revealed in the heights and peace on Earth to [those] of good will.

Luke 2:149

The song of angels is full of riddles. It begins with the well-known “Gloria,” with the splendor of the light. It is a Gloria that is carried upwards as praise and honor to the Highest. And it closes with a word that reaches into the depths, “eudokia.” Most often, this is translated as “good will” or “favor.” These two words—Gloria, doxa, and Good Will, eudokia—come from a common source in the original Greek text of Luke’s Gospel. Both point to one and the same light, which joins with the darkness, in the heights as well as in the depths.

For once, it steps into the earthly darkness and glorifies the night. For once, it steps out from the darkness of the heart and illumines it. It is this being of light, of whom the angels sing, and the shepherds adore. They do it with the gift of their devotion such that it radiates out from them. And among songs of praise and devotion, peace appears—not only on this Holy Night.

Peace lasts forever. It is this power that belongs to the sphere of the holy, and it is this that participates unceasingly in its effectiveness—even in the midst of wars prevailing upon the Earth. But, in order for peace to be effective on the Earth, there needs to be an in-between space wherein peace may be born. An open sky, a heaven, within us. For the peace of Earth can only be born in human beings—anew, again and again. With joy, we recognize the possibility of an eternally new beginning, one that radiates, golden, all around. Joy is the proclamation of the “Good News”, the birth of a “higher childhood,”10 a power for peace within us.

Translation Monika Werner, Eliza Rozeboom, Joshua Kelbermann

Images Miriam Wahl, watercolour on paper, 2022

Footnotes

- Luke 2:8–10 from The New Testament, translation by Jon Madsen (Floris Books, 2017), p. 144–45.

- Hermann Beckh, “Zarathustra,” in From the Mysteries: Genesis, Zarathustra, translated from the German by Alan and Maren Stott and Hannes Kaiser (Temple Lodge, 2020), p. 114.

- Hermann Beckh, “Zarathustra”; see note 2, p. 115.

- Rainer Maria Rilke, “Elegy 1,” in Duino Elegies: A New Translation and Commentary, translated from the German by Martin Travers (Camden House, 2023).

- Walter Friedrich Otto, Die Wirklichkeit der Götter: Von der Unzerstörbarkeit griechischer Weltsicht. [The Reality of the Gods: On the Indestructibility of the Greek Worldview] (Rowohlt, 1969).

- Luke 2:13; see note 1, p. 145.

- Translated from the German. Cf. Christian Morgenstern, “Oh Night . . .” in We Have Found a Path (Mercury Press, 1994).

- Pseudo-Dionysius (the Areopagite), The Complete Works, translated by Colm Luibheid (Paulist Press, 1987), “The Celestial Hierarchy,” ch. 3:1, p. 153.

- Luke 2:14; see note 1, p. 145.

- Novalis, Heinrich von Ofterdingen, translated from the German by Lyman Thurston and William Torry (Cambridge Press, 1842), pt. 2.

Een abstract filosofisch artikel dat voor mij niet bijdraagt aan een beter begrip omtrent vrede e.d. Wat in bredere context bij mij steeds de vraag doet rijzen in hoeverre de antroposofie na meer dan 100 jaar echt invloed gehad heeft in de wereld.