Friendliness is not a moral demand but rather an art free of intentions. It opens doors between people without any expectations. It’s a path of training running through our everyday lives.

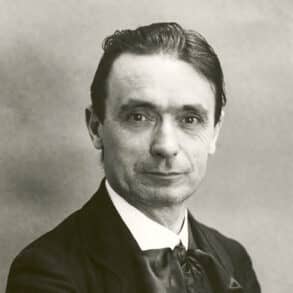

The playwright and poet Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956), who was spiritually underestimated and also underestimated his own spirituality, once placed “being friendly” alongside reading books, singing, and good food in his poem “Pleasures.”1 In other writings, he expressed the view that friendly behavior is not only pleasant for the recipient of the friendliness but is a benefit to the one being friendly. In a poem about a Chinese wooden mask of an evil demon, Brecht stated that it’s “exhausting . . . to be evil.”2

The virtue of friendliness ultimately takes aim at the will in the human soul. Even if I’m skeptical about someone else’s opinion, I can still decide to be friendly. Even if I’m not in a cheerful mood and don’t sympathize with someone, I can still create a positive interpersonal atmosphere by being friendly. I do neither of these things directly from out of my own being-as-such. But I can will to do them. I can try to be friendly—because the quality and gesture of friendliness move in the mysterious intermediate realm of freedom.

It’s like a door that I open, which remains open for everyone. It’s not what lies before or behind the door. Friendliness creates access. It allows ‘I’ and ‘I’ to encounter each other in a way that enables conversation.

Is friendliness—that graceful blend of distance and closeness, lightness and quiet seriousness—perhaps the most fundamental attitude of today? Are empathy, attentiveness, and appreciation, on the other hand, not “a little over the top”? Do they not, at times, have a gently insistent, morally demanding quality that, in some eyes, comes across as overly contrived, even saccharine? Friendliness as such wants nothing; it’s not a latent moral expectation. It’s an enabler. It doesn’t seek to make any statement about the value of another person, not even a positive one. It doesn’t make demonstrations. Friendliness is unintentional. It is an artist.

Naturally, friendliness can also become hypocritical and hollow, mere pretense and superficiality, and fall into simple convention. It can become stiff in formal politeness and even be debated as a virtue: “Should or are men still allowed to hold the door open for women today?” “Is politeness still a relevant value today?” Friendliness in the true sense of the word would not provoke a pros-and-cons discourse in this way. Everyone agrees about friendliness. Curiously, this includes even hostile political camps: those who tend to lack friendliness in their tone of voice subsequently perceive the structural sanctions imposed by others as unfriendly acts. Away from such ritual skirmishes, however, it’s the warmth of heart that marks a real boundary. Having a warm heart toward someone who openly discriminates against others, for example, is considered by some to be humanly impossible. Yet, in that case, friendliness can also fall into exaggerated pseudo-friendliness, into naive, sentimental “bridge building.”

Dynamic Equilibrium

Friendliness is the epitome of dynamic equilibrium, a state of suspension at the threshold, in which outcomes can develop in one direction or another through dialogue. In an encounter where I am friendly, I may agree or disagree, but I can always perceive and interpret how the other person reacts and respond accordingly. There is something playful, perhaps even experimental, about it. Friendliness creates dynamism.

It’s disarming. It’s the mode of the conscious soul, the harmony between ‘I’ and ‘I’. It’s the moral deed and not some kind of conjuring.

Certainly, friendliness has its siblings, like respect, openness, or interest. But still, we don’t usually sign letters “with interested greetings.” We keep our distance and thus show our respect, even if we have made a complaint in our letter. Emotions can rest in an atmosphere of friendliness; they remain spellbound. We educate ourselves through friendliness. It is the path of training running through everyday life, the path of training we’re already on when we leave the house each morning, get on a bus, greet our colleagues in the office, or our partner in the evening. It can be a decisive meditative moment of utmost consciousness when I notice during an encounter how the other is tuned, what they’re radiating, whether they are present in their own higher world, or whether I can perhaps help them to be, or help them to be the best possible version of themselves. I don’t “study” the other person like an object, and if I do happen to reflect on myself a little in my attentiveness, I can catch myself when I do. It’s the restraint involved in friendliness, its casual and imperceptible quality, that makes it so beautiful, so graceful, so liberating. It doesn’t make a fuss about itself. But it’s precisely this that opens the door to finer perceptions. It’s the threshold of contact that always remains perceptible: What is coming towards me, friend or foe? Thus, it questions itself. It studies and observes what is happening within itself, but remains in the mode of learning and exploring.

Free from Violence

Last but not least, friendliness also helps in the loaded terrain of intimate relationships. Friendliness doesn’t exercise power. It doesn’t need enemies and doesn’t seek to educate others. In a poem about a failed relationship, Brecht wrote, “We were not friends with each other / When we lay in each other’s arms.”3 The failure of marriages often stems from a lack of shared orientation and connection at a soul-spiritual level, and from neglect, even when love and sensual desire are present. In friendship, which is closely related to friendliness, one is attentive and “sees” the other for who they are and remains true to an archetype that one believes in, regardless of corporeal or social sheaths and roles.

When we lose sight of this archetype in the storms of life, we might bitterly accuse one another of being in the wrong boat while secretly fearing that we ourselves might be. But friendliness in the sea of the everyday is neither a boat carrying good people who do everything right, nor is it a cruise ship offering respite from the worries and hardships of existence. Friendliness is the fishing boat from which Christ calms the storm on the Sea of Galilee and comforts his friends.4

Friendliness is located in the place of our ‘I’. Strictly speaking, the ‘I’ is not a member of our being in itself, but rather transforms the others. As the ‘I’-organization, it orchestrates the interplay between the various levels. Thus, friendliness doesn’t have its own agenda but rather constantly determines and connects itself anew. Yes, perhaps commitment is the “sister” with whom friendliness is most intimate, alongside openness and respect, and to whom it feels most strongly connected.

Learning Generosity

Some time ago, I had two remarkable experiences on a train. This was one: I’m sitting at the back of a crowded high-capacity coach. A large Turkish family gets on in Frankfurt am Main. No sooner have they taken their seats in the table-seat row directly in front of me, than two of them, sisters perhaps, start talking on the phone to a third person, apparently to solve a complicated logistical problem. They keep passing the cell phone back and forth, talking loudly and intermittently for what feels like three-quarters of an hour. Opposite them, in the only seat still available in the table-seat row occupied by the family, sits an elderly man traveling alone. He keeps from saying anything for a long time, holding his tongue, until—apparently prompted by a glance or a “Do you have a problem?” gesture from the woman on the phone—he suddenly blurts something out indignantly. The woman reacts with corresponding irritation. The man begins to rant loudly and vehemently about the family and their behavior, indirectly portraying it as typical of foreigners. Immediately, two somewhat bourgeois-looking passengers from the surrounding rows stand up and reprimand the man. They do this in a way that is neither noticeably aggressive nor empathetic, but—as if it were simply inevitable —a gesture of self-evident democratic duty. The man then finds himself on the defensive, both socially and intellectually. He defends himself by asking why the other passengers were not equally outraged by the phone calls and why he alone is being singled out. When he suddenly begins to sing a German folk song, the general verdict seems to have been reached: a hopeless case and a troublemaker, a typical white old man. Shaking their heads, the two passengers return to their seats.

In another train, weeks earlier, in the quiet zone of a sparsely occupied high-capacity coach, a father with a strong Berlin accent who talks incessantly and his bright sixteen-year-old son, both wearing sweatpants, are engaged in lively conversation about the rail lines, apparently their shared hobby. They discuss signal boxes, line closures, and timetables intensely without a pause, and entertain the whole coach in which hardly anyone else is talking because most are traveling alone or are tired and lost in thought, staring out of the window. Every now and then, however, someone smiles. You can understand every word the two are saying and actually learn a lot about single-track lines, staffing problems, and diesel locomotives. No one complains. The father and his son seem protected.

Why was there so much serenity in this space but not in the other?

Perhaps it was a lack of engagement that paralyzed the parties involved in the train with the large migrant family, the “old white man,” and the “woke” passengers. Even between the family on the phone and the two fellow passengers helping them, there hadn’t been any noticeable connection, no inward involvement, no grateful smile, no inquiry—while in that other high-capacity coach, generosity in the literal sense of the word had prevailed, with space being made and an intimate, liberating friendliness being felt. All the fellow passengers silently allowed the father and son to share this space, perhaps because they were seen as human beings rather than as representatives of social postures. A disarming paradox: nothing about the two was “typical” because they were “types.” As father and son, i.e., as blood relatives, they treated each other like friends.

Friendliness as a Research Interest

“Oh, we / the we who wanted to prepare the ground for friendliness / Could not be friendly ourselves,” wrote Brecht in “To Those Born Later.”5 Where is such ground prepared? Not in class struggle. Not through the mere intention of wanting to belong to the good. But where I connect with the concrete phenomenon, before any evaluation, before any unconditional will, where I concern myself with the inner conditions of the other: How did you become this way? Friendly interest is actually always a research interest. No one, for example, showed any interest in the old man’s distress, his defensiveness, and his eccentricity. The smiles when he began to sing were ironic and mocking. He was just as much a lost soul, a stranger. Why did no one ask, “Why are you so indignant? Do you have no one left to support you?” Friendly interest as a research interest would also ask, “How is it possible that you have no perception of how intrusive it is to talk loudly and privately on the phone among strangers?” This can be observed just as often among fellow citizens who do not have a migrant background. And wasn’t it infinitely interesting and curious anyway that the man suddenly began to sing in the purest baritone?

Brecht ends his famous poem to future generations with a plea for forbearance, for tolerance [Nachsicht]. To forbear [nachsehen, literally, “to look after”] someone: what a complex word, and what a friendly one! The grim man on the train was also unable to muster this forbearance for the family—and in the end, in a completely different sense, he was forborne.

Does this dazzling verb, nachsehen, mean that one’s gaze remains fixed on the other person, accompanying them, seeing them, and remaining connected to them even when they’ve moved out of sight or out of the field of vision? How can I actively “look after” someone? Do I see something retrospectively? Do I retrospectively see the good in them that they were simply unable to activate where they were?

And does friendliness mean the same thing? Wanting to see, acknowledge, and address the good in others as a matter of principle?

Yes, even when we have made ourselves permanently unacceptable in the eyes of others, there must be someone who bears witness that we were once acceptable: a friend who soothes the storm in our soul—and who knows that we have nevertheless lived and tried our best.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Image Detail from Virtues by Laura Summer 2025: “Virgo Between flattery and rudeness find courtesy, be given tactfulness of heart”

Footnotes

- Bertolt Brecht, “Pleasures” [Vergnügungen] in The Collected Poems of Bertolt Brecht (New York: Liveright, 2018).

- Ibid., “The Mask of Evil” [Die Maske des Bösen].

- Bertolt Brecht, “Love song from a bad time” [Liebeslied aus einer schlechten Zeit] in Love Poems (New York: Liveright, 2015).

- Mark 4:35–41.

- See footnote 1, “To Those Born Later” [An die Nachgeborenen].