In this summer’s globally successful film productions, Barbie and Oppenheimer, darkness and brightness, depth and surface confront each other. It is no coincidence that the films premiered on the same day. [We offer a little spoiler alert for our readers who have not seen the movies yet.—Ed.]

Gigantic in size, Barbie lands in an enigmatic desert landscape where girls play with their old-fashioned dolls. They are playing mother and child and thus practising their “destiny” as women. But then the focus shifts from motherhood; Barbie becomes the symbol of a new femininity, the woman who can do everything, achieve everything, who unfailingly unites everything in herself. It is clear what is being said here: Barbie landed at the dawn of the 1960s not only in children’s rooms but in children’s minds. The arrival of Barbie changes their consciousness, which until then resembled a wasteland and is now filled with a new, transcendental ideal. This is how the film tells it. The little girls start smashing their baby dolls, and in 1959, a new age begins: Barbie, the perfect, unconfined woman, is born!

Parody of Paradise

Mattel, the company behind the Barbie doll and the film, tells a story here in which the Barbie doll is a pioneering figure for the emancipation of women in the twentieth century. Interestingly, in 2003, the Barbie doll was given wider hips and was less exaggerated in length. Two years later, the instruction was reversed. The message remains unchanged: no natural body for Barbie. In the film, we leave the world of bald baby dolls and tea sets and enter Barbieland, where people are always in a good mood, always compliment each other, the beach or disco is always on the agenda, the world is intact, and (!) Barbies are more important than Kens, the male counterpart. We are thrown into a glittering, smiling, twinkling world of pink plastic, which is fiercely parodied by director Greta Gerwig, who has become known for independent cinema. (Gerwig co-wrote the script for the film with Noah Baumbach).

The filmakers make use of an “uncanny valley” effect: the dolls’ homes are too small in scale. In this way, the art world remains the art world and does not pretend to be real, and does not push anthropomorphism too far because too much authenticity is off-putting—things must remain artificial and continue to offer the imagination a platform. The doll-like environment allows the characters to be only minimally—too minimally—like dolls. The overdrawn gloss of this soap bubble bursts when Barbie suddenly asks during a choreographed dance number: “Do you ever think about dying?” From then on, her journey to Earth begins, Barbie joining the earthly world. Much of it comes across as self-reflection and self-criticism of her own cultural contribution, until towards the end, Barbie does restore Barbieland, ascends her throne once more, and, along the way, heals the mother-daughter relationship of the other—human—main characters.

Reality as Hell

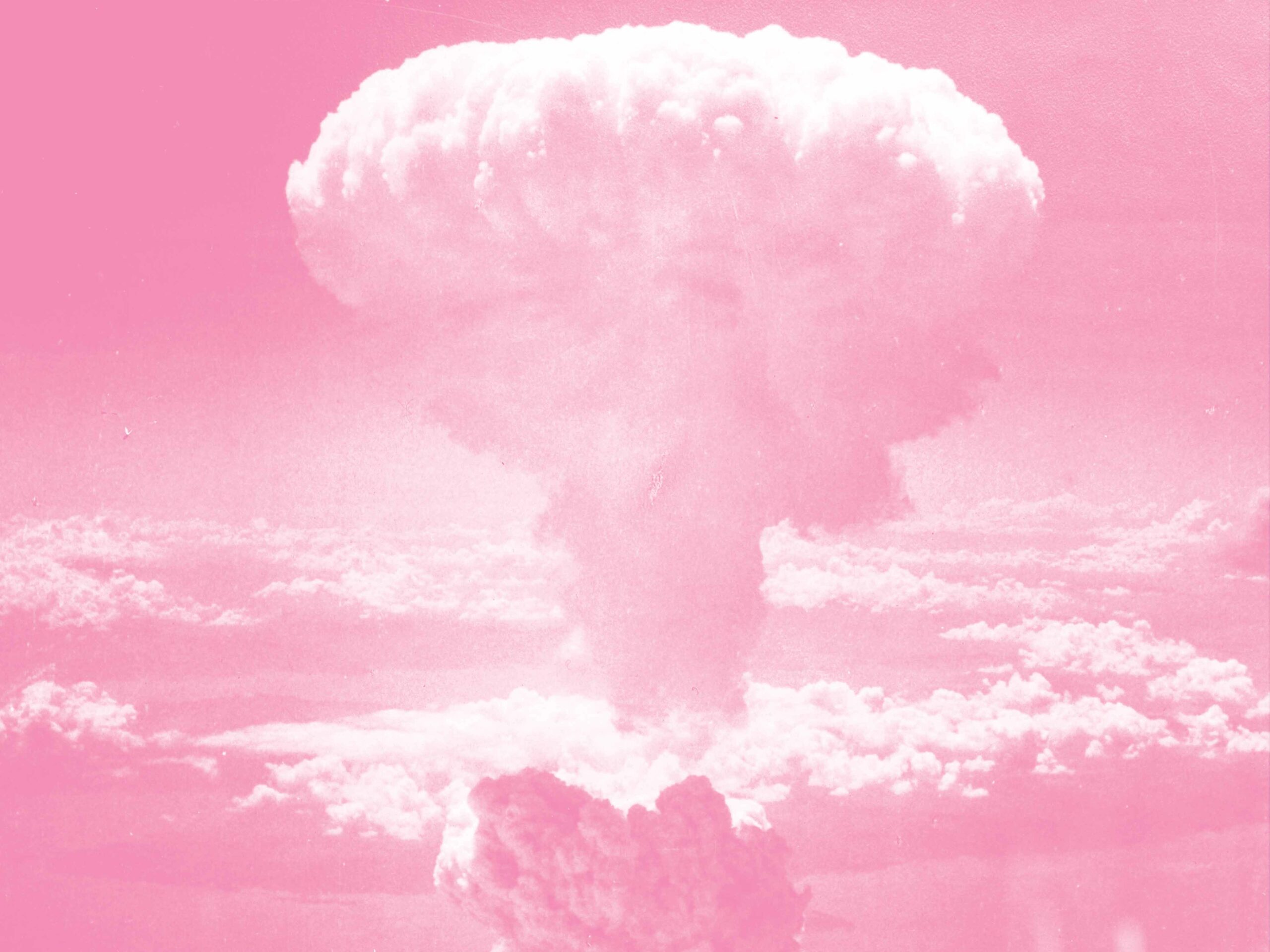

In Barbie, the immortal becomes mortal; the (fashion) goddess becomes human. In Oppenheimer, the human becomes God. This is a dark film of epic length about the scientist Robert Oppenheimer, who is considered the father of the atomic bomb. In contrast to Barbie, it presents a dystopian picture of the world. It juxtaposes the fascination with mastery of the world, the penetration, subjugation, and transgression of the laws of nature, and the fear of human violence and its unleashing. It is the portrait of a man whose genius and talent drive him to the brink of madness and, at the same time, into the depths of personality.

Visually, Oppenheimer contrasts the polarity of a world turned dark, in which eruptive, destructive forces are concealed, with pale, everyday events lacking in warmth. Time and again, the darkness culminates in the blinding unleashing of the power of the sun. We see inside Oppenheimer’s intellectual world, how he visualises his thoughts, how they come to life in movement, how he detaches himself from matter in thought, and how it lifts him into consciousness but without giving him warmth and making him more human.

Barbie, on the other hand, revels in its own optical superficiality, which is the same as the favoured plastic—the material that has no will. Everything that happens in Barbieland must happen effortlessly, without resistance—the colours are gaudy and cloying, and there are no shadows. Barbie glosses over any resistance; Oppenheimer lynches it. Both want to save the world and want eternal peace: the one through featureless niceness, where everyone is content in their role—fascism is what one film critic calls it—the other through abysmal might. Here, eternally bathing in the sun; there, predation of the sun. Both concepts threaten life—one in the frenzy of consumption and the other in the frenzy of destruction. That sounds familiar. Both characters reject responsibility—Barbie because she knows nothing about it, Oppenheimer although he knows about it, making Oppenheimer the much more substantial narrative.

In a time of uncertainty and ruptures, both narratives intentionally and unintentionally explore the longings, limits, and dissolution of boundaries in contemporary life. In the final sequences, when the camera moves to the faces of Barbie and Oppenheimer, sending their deep, sad and fragile gazes across the screen for a few seconds, there is a glimmer of hope. There, where what is human breaks through in a gaze that neither forgets itself in the plastic world, nor forgets the sun in Los Alamos, but wants to become the sun itself in its visage—that is where the center is, that is where the land lies between the fine lines that both films draw. So, the myth is located not in the visually stunning films but in this middle ground that the narratives of Oppenheimer and Barbie circle around.

Translation Christian von Arnim

Image Atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. Photo: Charles Levy, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain. Colour modified.