Last December 2022, after more than ten years of work, Rudolf Steiner’s three-part series of lectures and meetings given at the founding of the Waldorf School in 1919, commonly known as “The Teachers’ Course,” was finally published in Chinese.

The lecture cycle was presented to the Chinese reading public in China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Singapore, along with a celebratory online event. Translation work began in 2008 out of the far-sighted support of Nana Goebel and the Friends of Waldorf Education. Two translators and a group of Chinese editors undertook the translation of twelve basic works with the goal of providing a solid, scientific translation and corresponding terminology.

For the most part, they were able to retain the style of Rudolf Steiner’s language in order to offer the Chinese reader an experience comparable to the German. Of course, none of the content is ordinary, and if it is simply read like a normal book, the deeper significance does not become apparent. As with the German, many larger contexts only become clear when Steiner characterizes certain topics from different points of view. For this reason, it was especially important to keep the terminology consistent and clearly understandable throughout all the volumes. For instance, what if the terms “sensation” or “perception” were translated differently or even interchanged in different volumes? The whole epistemological basis of Anthroposophy—present in these works on education as a long-matured foundation—would no longer be clearly discernible. The works are founded on a theosophical-anthroposophical anthropology and include descriptions of the different members of the human being with their development throughout childhood and youth. Without a consistent language, the differentiations and subtle nuances of the real world of spirit and soul could not be understood as part of this study of the human being.

It is remarkable that the Chinese language, born out of the ancient East Asian world of wisdom and its Atlantean inheritance, is able to engage with another wisdom language: the language of spiritual science. Rudolf Steiner described the Chinese language as a “grandiose monument from the middle of Atlantean culture,” characterized by its wide variety of expressions and a certain kind of grammatical flexibility, which both reveal a state of consciousness oriented towards the surrounding world. 1 By way of these attributes, the dynamic, often unconventional, turns of phrase in Rudolf Steiner’s language can actually be reproduced considerably well in Chinese.

In this sense, what Ernst Bloch said about Hegel’s approach (which Steiner consequently took to its logical conclusion) applies here to Steiner himself: “Hegel’s language breaks the usual grammar because it has unheard-of things to say, for which the usual grammar offers no possible means.” 2 With his usual thoroughness and exacting method, Steiner carries this break with grammar further into the realm of supersensible realities.

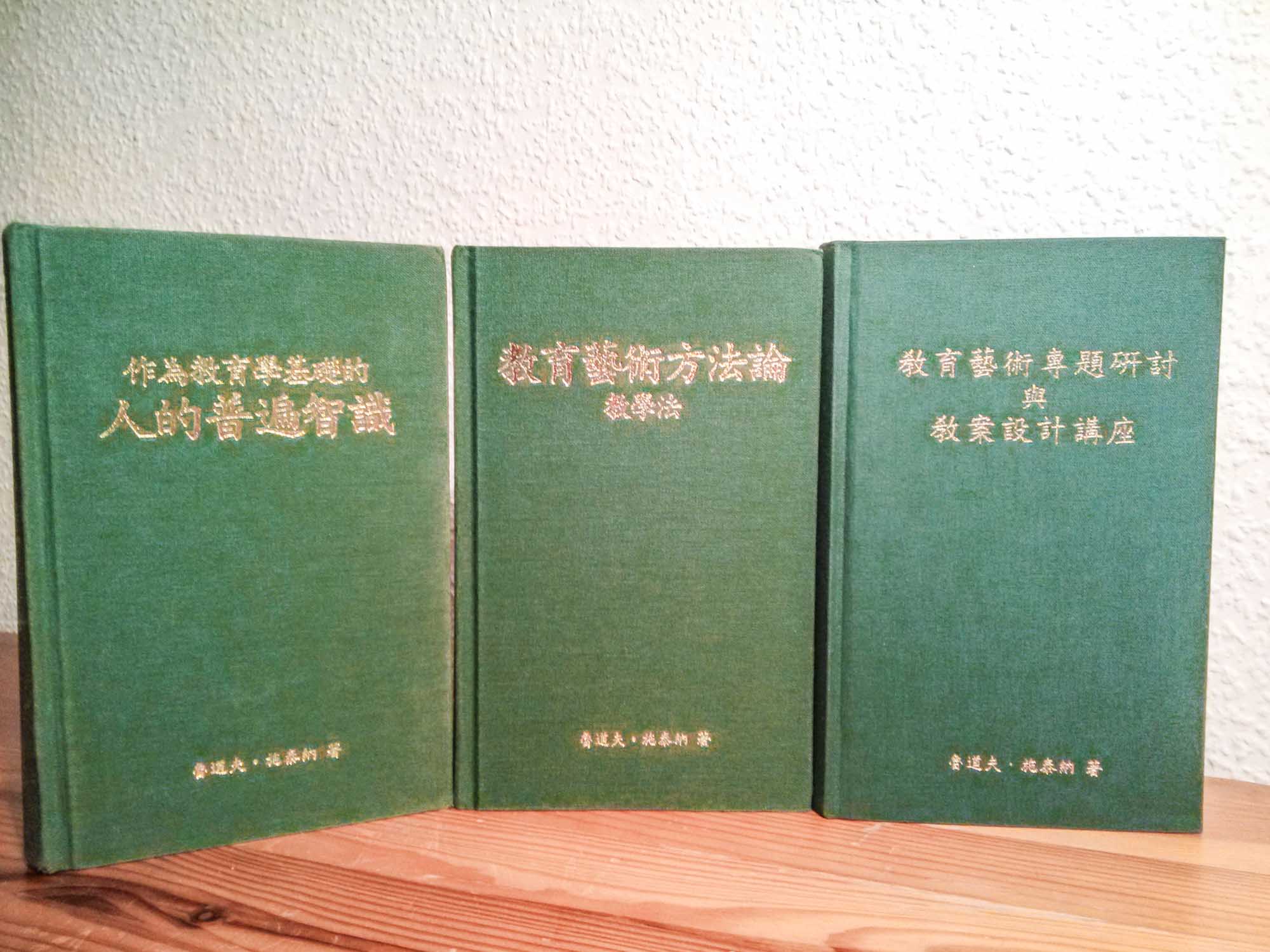

As Confucius said: “If the language is not correct, that which is said is not that which is meant.” In this sense, a translator is always walking on a tightrope. The group of Chinese translators and editors has produced other volumes over the years since the publication of Theosophy in 2011: The Philosophy of Freedom (CW4), Occult Science in Outline (CW13), Lucifer-Gnosis (CW34), and The Curative Education Course (CW317). A General Knowledge of the Human Being as the Foundation of Pedagogy (CW293) appeared in 2014, The Art of Education, Methodologically-Didactically (CW294) and The Art of Education: Discussions and Lectures of Lesson Planning (CW295) in 2022. The work on Knowledge of Higher Worlds (CW10) and Education and Teaching out of a Knowledge of the Human Being (CW302a) is currently in process. The group’s main focus has always been on Steiner’s unique linguistic style. The translators recognize that a simplification or even adaptation to classical or modern Chinese would make Steiner’s intended meaning unrecognizable or, worse, distorted. Steiner was not an old Chinese man! We must not turn him into one by merely assimilating his words! Why would a Chinese person care about Rudolf Steiner’s work when they are still intuitively connected to the ancient East Asian wisdom unless it contained a new contribution to spiritual knowledge?

Each book includes extensive footnotes, a glossary of common anthroposophical terms, a biographical survey of Steiner’s foundational works, and a description of how the Chinese characters used for the trichotomy of body, spirit, and soul were generated based on the academic study of the Chinese language. Chinese readers are thereby enabled to form their own independent judgment and to continue to deepen their work with the texts in their own independent self-study, no longer relying solely on the opinions or instructions of foreign lecturers.

To order the books, email berlin@freunde-waldorf.de

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Photo Astrid Schröter