Rudolf Steiner’s landscape design reveals a harmonious interplay between the building impulse and what was given by nature.1 Before construction began, the “House of the Word” was anchored co-creatively by Steiner in the world of the nature spirits. The mistletoe plant is found in dialogue between the building’s structures and as a mediator of the Goetheanum’s etheric sheaths. Mistletoe has formed a remarkable wreath around the Goetheanum landscape since its inception.

St. Odilia,2 the Grail Castle of the ninth century,3 and Count Cagliostro’s Rosicrucian-Masonic design4 are all silently present in the landscape of the Ermitage in Arlesheim [the largest landscaped garden in Switzerland and an important spiritual site]. These historical impulses across the millennia were fundamental to the building of the First Goetheanum. It was here (so the story goes) that Rudolf Steiner decided to accept the offer to move the Johannesbau (Johannes Building) project from Münich to Dornach. He chose a distinctive, free-standing natural rock formation as the starting point and “necessary” focus for the design of the building and its surrounding landscape.5 He redesigned the “Felsli” (literally, “little rock”) landscape as a plateau, providing it with a geometrical frame. Only then was it able to become dynamically active, in that its slightly eccentric circular shape could now collect and focus the forces in the sea of ethers.

Seven wide steps spiral out from the foundation wall and are “collected” back into the west side, turned away from the Goetheanum. Three little walls embedded in the meadow also emerge from the foundation wall in dynamic movement, fanning out like rays in the direction of the Goetheanum: one to the building’s center and onward to the distant Ermitage, one to the building’s entrance, and one more north-westerly, crossing in front of the building façade.6 They are like a threefold invitation to the Goetheanum building: from its spiritual heart in the foundation stone with its connection to the Grail events at the Ermitage, from its “face” with the red window, and from its mission in the world as a whole. For the elemental world, these triple walls are like energetic road maps, channeling directions. According to a number of esoteric reports, they can be understood as a “contract” Rudolf Steiner made with the elemental world before commencing construction.7 The “House of the Word” nourishes itself from the etheric forces that the spirits of the landscape bestow upon it. In return, it seeks to resound with inspirations back to the kingdoms of nature.

The First Goetheanum was a peaceful dialogue with the beings who shepherd the landscape and ensoul it with their life forces. Steiner took up their formative etheric streams and translated them into curving works of stone.8 The whole work culminated in a creative process that continuously opens up new experiential spaces for human beings and nature spirits.

The Twin Linden Trees on the Felsli

It is interesting to observe how the trees interact with these landscape impulses. Two linden trees were planted in 1908—only a few years before Steiner’s redesign of the Felsli—separated by “the length of a hammock.” One, more slender and towering, and the other, more cup-shaped, grew together over time into a harmonious interwoven crown. From this place, we can see the Goetheanum in its most beautiful half-profile, while behind us, in the west, stand the surrounding landscape’s distinctive mountains. Seminar groups have repeatedly perceived a vault of light in the root area of the linden trees, like a golden spiritual space, while, from above, this same light trickles down like an “etheric shower.” A few years ago, several mistletoe plants settled high up in the crown branches. The first mistletoe flower essence in the Goetheanum park was prepared in 2019 on the Felsli.

The impulse to research the healing forces of mistletoe flowers—in addition to the well-known preparations from the berries and leaves—was born at the Goetheanum in September 1999, on the fringes of the International Co-Worker Conference of the anthroposophical medical movement. There, I met a botanist who had been caring for mistletoe trees for decades in different natural habitats—including the Ermitage—as a part of their research into anthroposophical cancer remedies. The marvelous hornbeam at the Ermitage pond in the atmosphere of the Hornichopf peak, the hawthorn at the Rustic Temple directly above the so-called “Cave of Trevrizent,”9 the pines on the rocky ridge with a magnificent view of the Goetheanum, and the tall linden trees in front of the castle ruins: all were abundantly sown with mistletoe. They now provided a starting point for yet another sacred impulse. Carried along by the Grail atmosphere of the Ermitage, this healing stream has gone out into the world for many years now, from the many powerful mistletoe locations between the Mediterranean and the Oslo Fjord to the Carpathians and Caucasus. Step by step, a system of “Biographical Healing,” in harmony with the laws of destiny inherent to the ‘I,’ has emerged from out of the mistletoe essences prepared throughout Europe.10 But it was not until 2019 that the impulse to prepare mistletoe flower essences from plants in the Goetheanum Park came to full clarity. The setting for this initiative was formed by two distinctive elements of Rudolf Steiner’s landscape architecture: the Felsli and the semicircular little walls in the south. Within their parabolic focal point, Rudolf Steiner planted a pear tree, which has since been replaced by an apple tree.

Mistletoe around the Goetheanum

A glass bowl filled with spring water and fragrant, golden yellow blossoms sat at the foot of the Felsli’s twin linden trees with their mistletoe spheres, and, at the same time, another bowl sat under the apple tree, itself overflowing with mistletoe. A large seminar group witnessed the event. We experienced strong sensations of the resonance between the interior of the Goetheanum and its etheric sheaths. Central to this was the Foundation Stone. It seemed that it had temporarily created a kind of biological outpost for itself in the apple tree. In the year that followed, other flower essences were created around the Goetheanum. But most significantly, in the foreshadowing of the Corona Spring, the task became clear to combine the healing powers of bees with those of mistletoe and, at the same time, to open to the entire course of the year and go beyond the limited time window of mistletoe’s blossoming at the end of winter. The preparations took a year. Over the course of that year, in the outer stillness of the pandemic, there was an opportunity to train our perception of the landscape. One year later, a surprising sight opened to our inner eye: the Goetheanum, lifeless, as if in a coma brought on by the lockdown, appeared wrapped in a powerful but gentle, spiritual glow, carried in particular by the mistletoe. Specific places glowed like a promise of further possibilities, still unlived by the current undertakings. It seemed to us that the world of beings in the etheric environment continues to carry Rudolf Steiner’s intentions further, while at the same time, they approach us from the future.

A Wreath of Light

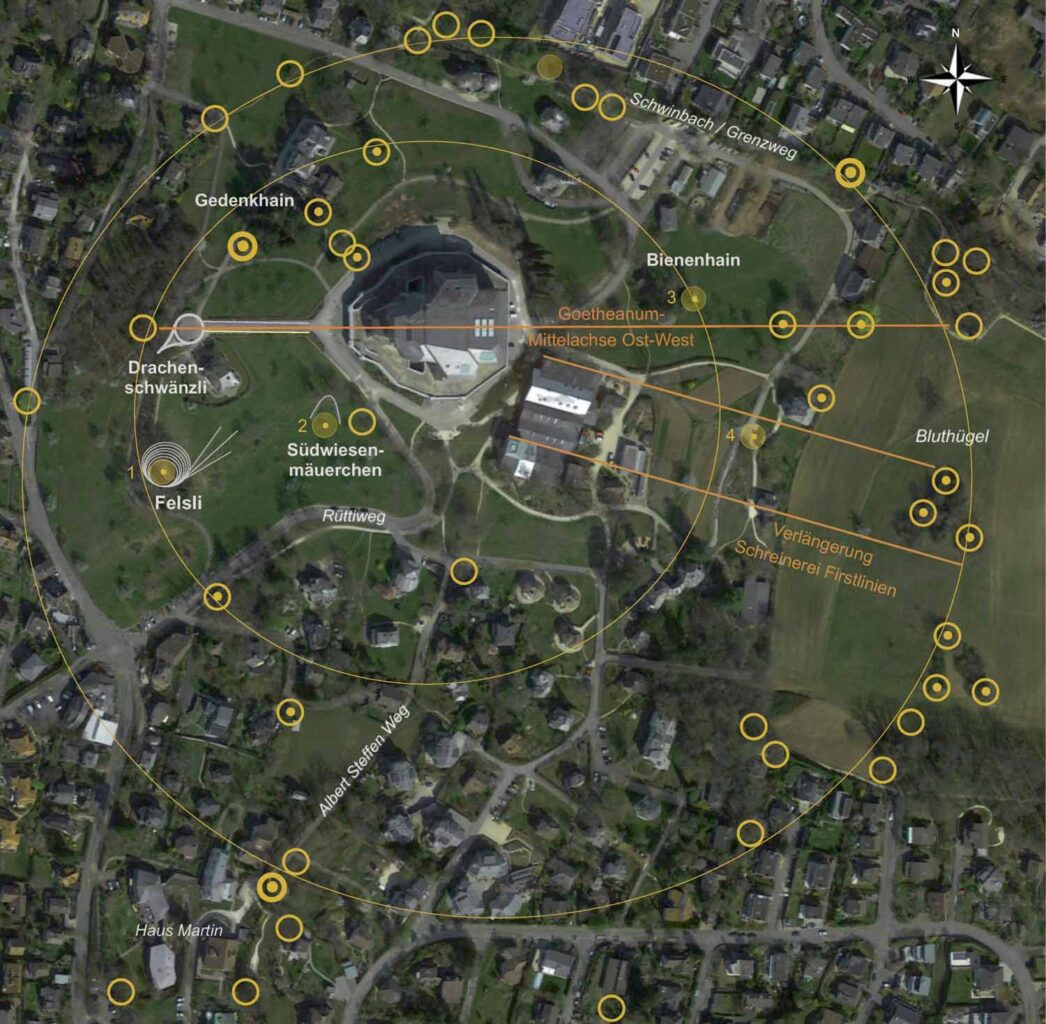

Growing on a variety of trees in a wide arc around the building, mistletoe plants stand out as a kind of special organ in these etheric sheaths—like a band of pearls. Some of these points of light are directly related to Steiner’s visible landscape design. For example, the linden mistletoes, in their majestic heights, stand in the grove below the cul-de-sac opposite the west entrance, in an exact extension of the building’s east-west axis. Others function as “threshold guardians” at the access paths where visitors enter the inner space of the Goetheanum grounds—for example, the magnificent spheres in the maple trees on Rüttiweg, opposite the entrance to Philosophenweg, and in the gnarled overgrown distinctive tree at the entrance to the narrow “grove” on Albert-Steffen-Weg, above Haus Martin. On some paths, the mistletoes follow the natural features of the terrain, as when they line the border of the Goetheanum grounds at Schwinbach or where they mark the upper end of the Goetheanum garden between the student residence and Kepler Observatory. Here, in the east of the Goetheanum grounds, there is actually a double ring. The beautiful mistletoes in the islands of trees on Blood Hill breathe far into the landscape above the Goetheanum, in the direction of the Dorneck Castle ruins and Gempen. They also connect us with the historic genius loci—the battlefield of 1499—with its dual quality of Michaelic and Helvetic courage, of freedom, and unrestrained brutality.11

Relation to the World

In the west, the Memorial Grove holds the urns of Rudolf Steiner and many of his closest collaborators. For a few years now, it has been framed on both sides by mistletoe. The young yet vigorously growing maple mistletoe at the entrance gate is particularly characteristic. One can experience how it “looks” toward Basel, toward the high-rises of the financial metropolis, and conveys this reality to the Goetheanum while it reciprocally picks up the events of the west façade’s red window, radiating them out into the world of the present.

Down in the southwest, the “Mary Magdalene” essences were created in late winter at the beginning of 2023. These consisted of a linden mistletoe, which made its way from the ruins of Dornach Castle, across a characteristic preparation site between the Dragon’s Tail and the Felsli, all the way to the south of France, to the place where the “Holy Marys of the Sea” arrived and worked.12 While making the preparations at the Sainte-Baume grotto, a clear and powerful connection was felt with the Arlesheim sites of Odilia and the Grail. And, as if shimmering all throughout, an appeal came for the future developmental possibilities for the Goetheanum—perhaps, as a synthesis of the coming, more feminine spirituality and the Michael Current?

For the first time at Pentecost 2023, a larger working group developed mistletoe flower complex-preparations for the needs of the present, which also are related to health. With this work, the four (or twelve) cardinal points around the Goetheanum had a stronger influence than ever before. It seemed to me that the unusual way in which the most recent essences were created speaks clearly of the multi-layered field of action of the Goetheanum. What happens inside the building, in terms of the cultural creations and international encounters, is intrinsically connected to an outer sheath. And it seemed that Rudolf Steiner modeled the “skeleton and blood circulation” of this sheath into his design of the landscape and planting of trees. The mistletoes have come along as special sense organs “in just the right places.”13

The awakening “to [a] powerful presence”14 can also assume dramatic features, as when, for example, on the summer solstice 2023, a thunderstorm snapped the larger of the two Felsli linden trees, and with it the prominent mistletoe. Similarly, in the summer of 2022, the distinctive apple mistletoe of the little walls in the south, along with its host tree, withered away. It was as if, precisely at the halfway mark between the centennial anniversaries of the Goetheanum Fire and the Christmas Conference, the spirits of nature had brought a message: “Now you must be strong and carry these forces yourself!”

On the other hand, in recent years, many mistletoe shoots grew larger, and in a remarkably short time, several new ones have sprung up. They seem to all be connected with each other in a continuous stream of spirit, the Goetheanum standing in the middle. Certain sites seem to have special functions, giving an overarching ordering and signaling to the whole, also “speaking” to the organs in the more distant landscape. As a working hypothesis, it seemed fruitful to relate our meditative perceptions of the mistletoe plants and trees to the inner core of anthroposophy, to the visible and recently published impulses of Rudolf Steiner as landscape architect, as well as to the current initiatives seeking a renewed world society.

Contact MistleTree Essences, Baldron

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Title image Mistletoe on the campus of Goetheanum, Photo: Xue Li

Footnotes

- Marianne Schubert and Stephan Stockmar, Man schaue was geschieht: Rudolf Steiner als Landschaftsarchitekt am Goetheanum (One Sees What Happens: Rudolf Steiner as Landscape Architect at the Goetheanum) (Dornach, 2022).

- Michaela Spaar, Odilia: Lebensspuren und Heilimpulse (Odilia: Traces of Her Life and Healing Impulse) (Futurum, 2014).

- Werner Greub, How The Grail Sites Were Found (Willehalm Institute Press, 2001).

- Hans-Rudolf Heyer, “Der Einfluss der Freimaurerei auf die Eremitage zu Arlesheim” (”The Influence of Freemasonry on the Hermitage at Arlesheim”), Unsere Kunstdenkmäler (Our Artistic Monuments) 44, no. 1 (1993): 38–52.

- In a meeting about the building, half a year before the laying of the Foundation Stone in 1913, Rudolf Steiner described the Felsli as “necessary.” See Schubert and Stockmar, p. 149.

- The site plan from 1915 shows the extension of the little walls to their target points within the building, as well as the underground packing of limestone sunk up to 2.5 meters into the ground as curved lines, whose extension connects the Felsli with the middle and east wall of the building.

- Fritz Bachmann, Getragen von Engeln und Elementarwesen: Die ätherischen Hüllen des Goetheanum (Carried by Angels and Elemental Beings: The Etheric Sheaths of the Goetheanum) (Oratio, 2003). Tanis Helliwell, Summer with the Leprechauns (Tanis Helliwell Corporation, 2011).

- In a similar way, ancient fountains often sensitively incorporate the streaming forms of water and create an ideal physical body for the nymphs of the wellspring.

- See Greub.

- See Helseforhandleren.

- The Battle of Dornach, a decisive moment in Switzerland’s independence from the Habsburg Empire, covered a wide area between Dorneck Castle and the Birs River.

- Provençal tradition identifies the beach at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, at the mouth of the Rhône in the Camargue, as the place where Mary Magdalene entered the European continent along with her sister and friends. The legend also tells of her retreat into a grotto in the sacred Sainte-Baume mountain.

- Rudolf Steiner speaks of tumors as “formations of sense organs in the wrong place” (in regards to the human organism) and carries this train of thought further with mistletoe therapy. However, in terms of production and field of activity, the anthroposophical cancer remedies made from the berries and leaves of mistletoe have nothing in common with the mistletoe flower essences.

- Zodiac mood of Capricorn from Rudolf Steiner, Twelve Moods, in CW 40 (Mercury Press, 1984).