We don’t believe in progress anymore—unlike during the era of industrialization, when it promised prosperity for all. Where are the new heroes and heroines of the “working class,” and where are their realms of activity? Reflections from a trip to Manchester, UK.

Oldham, a suburb of Manchester, looks decidedly shabby. What comes across as laissez-faire and charming in France—where people are more likely to spend their money on good food—is simply poverty here. There are few things of beauty, little of value, untended front gardens, and crumbling facades. The back alleys, lined with garbage cans, overflow with weeds. Old spinning mill buildings, like the Majestic Mill, are everywhere. The era of industrialization has left its relics behind, but no artists who wanted to populate these buildings. No art either, and no ideas for new social forms.

Within an afternoon, you have seen what there is to see, namely that poverty is a dimension of discrimination. I wonder where the “working class heroes” have disappeared to. Who cares about them anymore? The people here are nice, helpful, and open, even if they are a little overweight from food that no longer has much nutritional value but is cheap. They spend much less time on their cell phones than people in Germany do. On the trains and buses, there is more communal conversation.

The 50-minute journey from Oldham to Manchester city center, on a double-decker bus operated by the state-owned Bee Network, costs £2 and runs every 10 minutes. Then you flow into the hustle and bustle of the city, which doesn’t feel much different from London. The Central Library, next to the town hall, is pretty busy. An old man with a bent back plays the piano in the cafeteria. There are some souvenirs available at the information point, all featuring bees. The woman at the counter tells me that the worker bees have been the emblem of Manchester since 1842. They represent the solidarity and resilience of the “working class.” The city was the “hive of industrialization,” where workers toiled for the greater prosperity of all. The Manchester bee is also a symbol of the belief that societies can only overcome difficult challenges if they stick together.

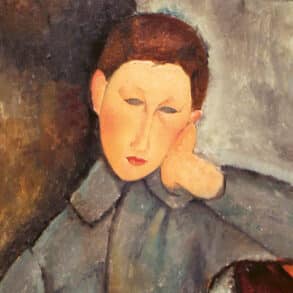

Admission to the Manchester Art Gallery is free. Here, too, crowds flow back and forth. In the dimly lit “Take a Breath Room,” you can sit in one of two armchairs and enjoy your lunch break in peace while viewing a single painting. Or, you can take a quick stroll through the exhibition, which reimagines gallery spaces. Everyday objects are displayed alongside old paintings to create new associations. The curatorial team is working with aspects such as the climate crisis, work, migration, identity, connectedness, and happiness. The team also has a seat on the city council. The John Rylands Library displays a section of text from A Bird’s Eye View of Manchester from 1899, which captures the spirit of the city: “Radical and rebellious, independent and progressive. Admired for its industry and reviled for its fumes, the world’s first industrial city nurtures a belief in democratic change. Something began in the early 1800s that still echoes today.” In the library, there is an archive of activists who wanted to make the world a better place. It documents local and global efforts to fight poverty, reform religion, and end inequality.

Loss of a Promise

In the evening, in my five-square-meter mini-room in Oldham, I imagine Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish-German revolutionary, looking up at the sky from her prison cell. People certainly dedicated their lives to agendas back then, but they had a different view of the “working class.” Progress also meant progress in social justice. Today, however, 83 percent of Germans no longer believe that the future will be better.1 It seems that capitalism has not kept its promise. In his book Verlust—Ein Grundproblem der Moderne [Loss: a fundamental problem of modernity], sociologist Andreas Reckwitz describes everything we have lost since the beginning of this era. Yet, this narrative continues to serve us well. Even the immense losses of World War II could be framed as “temporary” because the economic miracle of the 1950s and 1960s perpetuated the paradigm of progress. Today, however, according to Reckwitz, we live in a culture that is skeptical of progress. Where that will lead is still completely open. For about 15 years, Reckwitz says, fears of loss from various sectors in Western societies have been accumulating and intensifying. We fear losing our jobs, our homeland, our identity, our planet, and our sense of community. Progress is no longer the belief that my children will have a better life. Today, “progress” is the attempt to preserve the values we have already achieved. We have become a “society of singularities,” in which progress mostly refers only to personal happiness. Have we run out of political utopias? Where, in any of this, is the “we”?

Decommodification of Utopia

Everything that turns people into a commodity can only lead to loss, I think to myself. Perhaps even to a loss of self-respect? Or, to put it another way: anything that doesn’t commodify human beings will create the free space in which utopias develop. Could Oldham’s shabbiness be a protest against capitalism, which makes us believe that we need certain things to maintain the appearance of prosperity?

“A working-class hero is something to be. If you want to be a hero, just follow me,” sang John Lennon, who was born in Liverpool, 74 kilometers from Manchester. In the 1980s, John Berger wrote words dedicated to the striking miners in northern England, saying that he would protect any hero who stood up to the ruthless. “But if, while I am giving him refuge, he tells me that he likes to draw, or if it is a woman and she tells me that she has always wanted to paint but never had the opportunity or time, then I will protect them. If that were to happen, I think I would say: [. . .] I can’t tell you what art does or how it does it, but I know art has often judged judges, called for retribution for innocent suffering, and shown the future the suffering of the past so it would never be forgotten. I also know that the powerful are afraid of art when it does this, in whatever form it takes. Such art circulates among the people like a rumor and a legend because it provides meaning that the brutalities of life do not. It unites us because it is ultimately inseparable from justice. When art has such a function, it becomes a place of encounter for the invisible, the irreducible, and the enduring.”2

Translation Laura Liska

Photo Gilda Bartel

Footnotes

- Statista.

- John Berger, Begegnungen und Abschiede—Über Bilder und Menschen [Encounters and farewells – about pictures and people.] Hanser, München 1993.