Marginalia from the life and work of Rudolf Steiner.

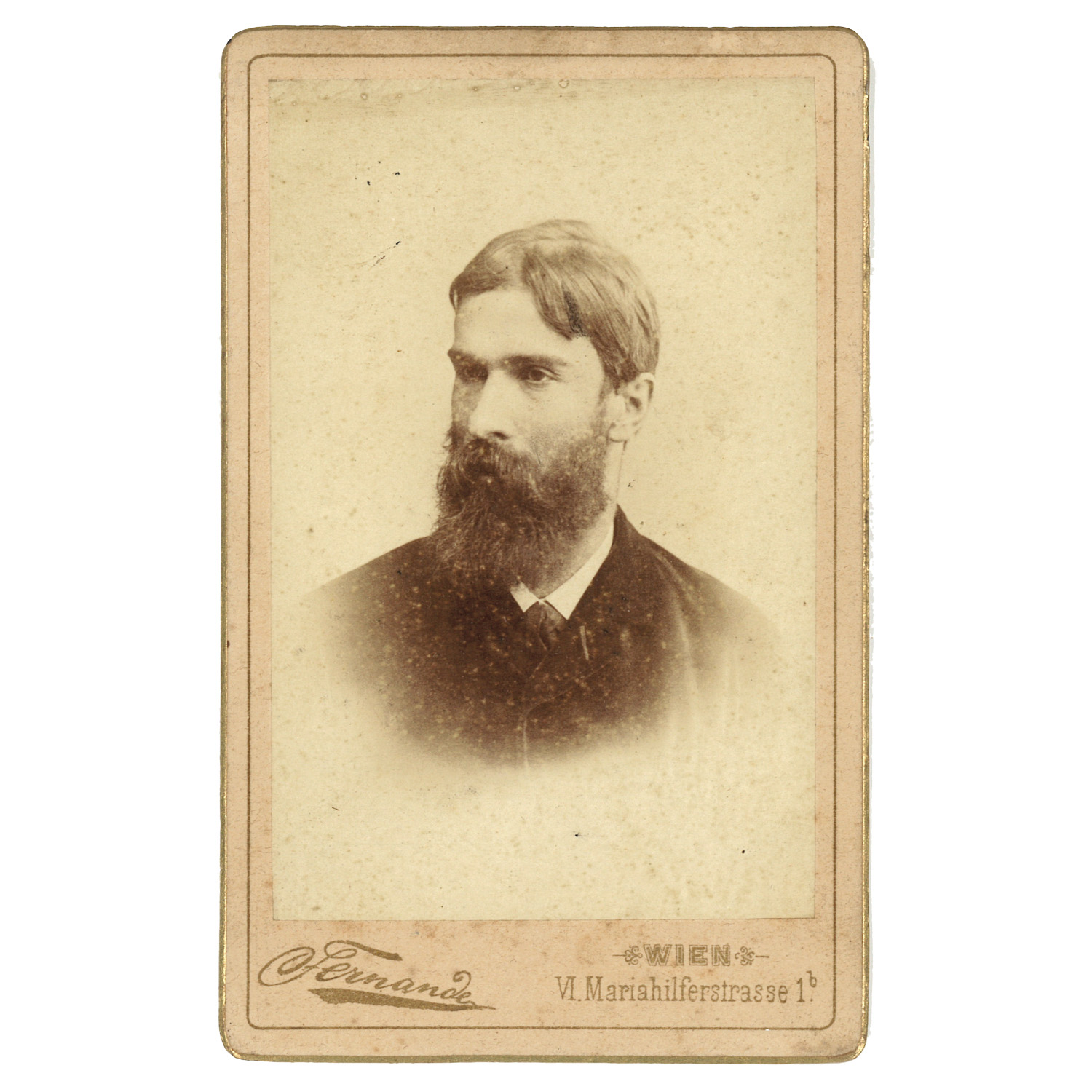

In his lecture of July 11, 1916,1 Rudolf Steiner described in detail how he met the Austrian mathematician and professor Oskar Simony (April 23, 1852–April 6, 1915) of the Institute for Soil Cultivation [Institut für Bodenkultur, today part of the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences]: “We encountered each other one time (I know it as if it had been yesterday) on Salesianergasse . . . in Vienna. I knew him by sight; I had never spoken to him. He didn’t know me at all; we just met as two people walking past each other on the sidewalk. At that time . . . I was a young pup of twenty-six, twenty-seven years old.2 So, Oskar Simony peered at me, remained standing (I’m just telling you a fact), and started a conversation with me about all sorts of things about spiritual science, then took me to his house and gave me his latest publication on an extension of the four types of arithmetic, which he had published in the old Academy of Sciences at the time.”3 Published in 1885, [Rudolf Steiner kept his copy of] this small work On Two Universal Generalizations of the Basic Algebraic Operations, which bears the inscription: “To Mr. Rudolf Steiner, in friendly esteem, the author.”4

We have Ernst Müller to thank for the more exact knowledge of how Oskar Simony once addressed Rudolf Steiner. He probably confided these words to Müller in person, which he had used at the time to address Steiner: “You are an occultist.”5 And Emil Bock added that he had said: “I would like you to come to my house with me, for I have an important question for you.” This important question was: “Is there reincarnation?”6

Dimensions

Rudolf Steiner characterized Oskar Simony as a person “who, in every way, tried to live into the spiritual realm.” Friedrich Eckstein (1861–1938), who was a close friend of his, tells us how Simony—a hulk of a man—went on many excursions and tours throughout his life, collecting plants and butterflies. Like Eckstein, he was also an enthusiastic alpinist, and the two met by chance on a mountain tour and became friends. Their conversations immediately turned to higher mathematics. Simony was interested in “higher manifolds and spatial dimensions” and had thus “taken special notice of the works of the famous Leipzig astronomer Friedrich Zöllner, who, in his Scientific Treatises [Wissenschaftlichen Abhandlungen], had expressed bold and often very fantastic ideas on this subject.” Zöllner increasingly occupied himself with spiritualism and worked for some time with the American medium Henry Slade. Eckstein reports: “Among the spectacular phenomena that Slade had produced in Zöllner’s presence, it was especially the mysterious tying of knots in a closed loop, bound together and sealed at the ends, that caused Zöllner the greatest excitement. . . . Simony . . . now began, in his own way, to deal in-depth with the problems of interlacing ribbons and knot formations, and after endless efforts he succeeded in bringing in a completely new systematic order into this world of shapes and concepts. What he found in his many years of work, however, was not so much empirical proof of the existence of higher spatial dimensions or of beings inhabiting them, but rather an entirely new geometric-topological approach to the problems of prime numbers and their law of formation.” In 1881, Simony published a booklet about his studies titled: Generally Understandable and Easily Controllable Solution to the Problem: “To Make a Knot in a Closed Ring-Shaped Band” and Curious Related Problems.7

When Rudolf Steiner met Oskar Simony, he recalled it was the time “when the Austrian Crown Prince Rudolf, together with Archduke Johann . . . were concerned with the unmasking of a medium8 and with such things in general. That is why there was a lot of talk about such things in Vienna at that time . . . .” Simony was also once invited by high authorities to take part in a spiritualist meeting with the aim of unmasking the medium. The host then asked him for his judgement as a physicist. Simony replied by comparing “’the emergence of occult phenomena with the formation of crystals from a saturated solution. … [H]ere, the forming of beautiful shapes requires the necessary duration, warmth, darkness, and complete stillness. … But, when one … agitates a salt solution with a rod, then no crystals can form.’ After this conversation, Simony was no longer invited there, and none of this was very conducive to his career.”9

Above and Beyond the Pain

When Eckstein once asked him along which paths was he able to penetrate such depths of thinking as his mathematical discoveries required, Simony explained that he had been brought up by his father from an early age to endure physical pain with a certain equanimity: “Well, there are few things that hurt as much as intense contemplation, when it is driven beyond a certain point. This is the moment when most give it up. But, the ability has been instilled in me to endure this kind of pain, and so, at times, I get above and beyond the point at which others throw everything away in order just to find calm. But, the new insights often lie just a small step above and beyond this point.”10

Oskar Simony “was indeed occupying himself . . . with these things, very scientifically,” according to Rudolf Steiner. In his mathematical research, he was above all interested in that which concerned the transition “from the three-dimensional to the four-dimensional.”11 He described Simony’s book To Make a Knot in a Closed Ring-Shaped Band as “very interesting.”12 At the teacher’s faculty meeting on December 18, 1923, Rudolf Steiner recommended it for working with a pupil. The phenomenon of “twisted strips of paper” was unknown to the teachers, so he showed them “how a strip of paper pasted together to form a closed loop crossed itself in the middle when twisted one, two, or three times.”13: “One twist resulted in a large ring; two twists resulted in two rings, one within the other. With three twists, the result was a ring knotted in itself.” According to Ernst Lehr, Rudolf Steiner used his Swiss Army knife and cut the strips of paper “in complete silence,” even though it was around two o’clock in the morning: “We looked at the strips afterward and discovered that they had been cut in a completely straight line exactly in the middle.”14 All the while, he talked at length about his encounters with Simony.

Humor as Mobility of the Spirit

Looking back on the encounter with the mathematician, Rudolf Steiner especially emphasized his remark about humour: “Well, while we were thus talking, he [Simony] made a pause in his remarks and said, ‘Oh, when one is dealing with these things, actually a lot of humor is needed!’ And truly, it is necessary, especially when one goes into the depths of spiritual science, that one does not unlearn humor, that, in other words, one does not feel continuously obliged to wear a tragically elongated face. And I am even convinced that Oskar Simony had lost his sense of humor in the last period of his life before he reached his tragic end.”

In a lecture given in 1913, Rudolf Steiner explained in more detail what is meant by “humor.” Simony “said, ‘When one is a serious researcher dealing with spiritual science, humor is necessary.’ This does not mean clowning around, but rather mobility of spirit, which, indeed, can sometimes be quite uncomfortable for those people who swear by principles.”15

This Side and the Hereafter

In a conversation with the Viennese mathematician and anthroposophist Ernst Müller (1880–1954) in Munich in 1913, Rudolf Steiner made some remarks about Simony, “not about his knot experiments, but about his generalization of algebraic operations. Dr. Steiner, indeed, saw in the forms of operation as modified [by Simony], the means of mathematically approaching suprasensible processes . . . .”16 In response to this indication from Rudolf Steiner, Müller wrote to Oskar Simony in the spring of 1914. At that time, Simony was already very hard of hearing, but Müller communicated with him quite a lot until he was called up for military service: “Instead of allowing me to meet him, he trudged up to my apartment himself with heavy steps. I drew his attention to Steiner’s lectures, which, in a curious way, he had indeed already known. He behaved evasively and, in his stormy manner, refused to read the theosophical lectures, slamming one of the books [R. Steiner’s Theosophy] on the table and declaring that he only wanted to discover what would happen after he died.17 Even so, he took the whole thing so seriously that he crudely inscribed the Statutes of the Society verbatim in his diary, which I was given a glimpse of after his death. The deeper reason for his rejection, as could also be seen from his diary, was that as a young man, he had been severely attacked in public by Prof. [Moriz] Benedikt by way of his interest in spiritualistic phenomena. Strangely enough, he also had a conversation with my father during one of his frequent visits and promised him to dissuade me from anthroposophy.”18

One year later, Simony’s life came to a tragic end. After a stroke, he (already severely hard of hearing) was now also paralyzed on one side. Notwithstanding his practice of enduring physical pain since childhood, he was unable to cope with his severe physical limitations and threw himself out of a window.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Rudolf Steiner, Toward Imagination: Culture and the Individual, CW 169 (Hudson, NY: SteinerBooks, 1990), lectures in Berlin from June 6–July 18, 1916. Unless otherwise noted, Rudolf Steiner’s remarks are taken from the lecture on July 11, 1916.

- The meeting must therefore have taken place in 1887/88. The fact that they met in Salesianergasse suggests that Rudolf Steiner was coming from Karl Julius Schröer, who at the time lived there at No. 10.

- According to Ernst Lehrs, there were two encounters. The first took place in Mariahilfer Strasse. See Ernst Lehrs, Gelebte Erwartung [Living expectation] (Stuttgart: J. CH. Mellinger, 1979), p. 340 f.)

- In Rudolf Steiner’s library under the shelfmark RSB Ma 28. Orig. Germ. title: Über zwei universelle Verallgemeinerungen der algebraischen Grundoperationen.

- In a transcript of his memoirs (Manuscript, GOE, p. 22)

- Emil Bock, The Life and Times of Rudolf Steiner, vol. 1: People and Places (Edinburgh: Floris, 2008). This statement has only come down to us from him; it is not known who gave it to him.

- Friedrich Eckstein, “Alte unnennbare Tage!”: Erinnerungen aus siebzig Lehr- und Wanderjahren [“Old nameless Days!”: Memories from seventy years of Teaching and Wandering]. (Vienna: Atelier, 1988, repr.), p. 65. Oscar Simony, Gemeinfassliche, leicht controlirbare Lösung der Aufgabe: „In ein ringförmig geschlossenes Band einen Knoten zu machen“ und verwandter merkwürdiger Probleme (Vienna: Gerold & Comp., 1881). See also Johann Carl Friedrich Zöllner, Transcendental Physics: An Account of Experimental Investigations from the Scientific Treatises (London: Harrison, 1880).

- The “unmasking” of the medium Harry Bastian by the Crown Prince and Archduke was reported by the Neue Freie Presse [New Independent Press] on February 13, 1884.

- Eckstein, p. 75. Simony also studied Mabel Collins’ Light on the Path and sought the opinion of Ernst Mach, whom he held in high esteem. Mach wrote back to him on November 9, 1887: “I am sending you back the book Light on the Path with my best thanks. In view of the poetic way of expression, which has probably lost some of its specificity through translation, it is difficult to clarify how much truly stands in the writing and how much one reads into it, but as far as I can see, I would like to draw out of my own basic approach approximately the same practical consequences that are contained in the writing. To what extent the basic theoretical approach coincides, I do not dare to decide. It is interesting and important and instructive to me that one cannot speak here of the pure asceticism that one usually imagines.” (Eckstein, p. 71 f.)

- Eckstein, p. 67.

- Lecture on May 30, 1904, GA 52. Available in English in The History of Spiritism. And, The History of Hypnotism and Somnambulism. Two lectures delivered in Berlin, May 30 and June 6, 1904. (New York: Anthroposophic Press, 1943).

- Lecture on July 11, 1916, CW 169; see footnote 1.

- Rudolf Steiner, Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner, vol. 2: 1922–1924, CW 300c (Hudson, NY: SteinerBooks, 1998), pp. 694–95. Translation by Robert Lathe & Nancy Parsons Whittaker.

- See footnote 3, p. 341.

- Lecture on Feb. 6, 1913, in Rudolf Steiner, Fragenbeantwortungen und Interviews [Answers to Questions and Interviews], GA 244 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2022), p. 441.

- Ernst Müller, Geistige Spuren in Lebenserinnerungen: [1880-1914]. [Spiritual Traces in Life’s Memories]. Typed manuscript, Leo Baeck Institute, New York.

- In another transcript of his memoirs (see note 16), he mentions: “When I once wanted to give him Theosophy, he threw it to the ground with his usual impetuosity; he wanted to wait until his death, as the secrets would then be revealed to him anyway.”

- Ibid., p. 45 f. After Simony’s death, Ernst Müller reproached himself for not having forwarded a question of his to Rudolf Steiner: “It is perhaps my fault that I did not build the bridge that I could have prepared for the Lone One. At the time, he wanted to hear your judgment on his scientific research, and I had simply forgotten to tell him. How little love is free in the world that this man did not find that little, which would have shaped his destiny to be little more kind.” (Undated letter, ca. April 1915, Rudolf Steiner Archive, Dornach)