The production of animal products is criticized as being harmful to the climate. Cell-cultured products, which are grown in vitro from animal cells, are promoted as good alternatives. Are these really more climate-neutral, and what is the real cost—physically, mentally, and spiritually?

“Cellular agriculture” develops agricultural products from cell cultures using biotechnology and synthetic biology.1 No farm is needed for production, but instead, tissue-specific stem cells are taken from living animals and grown in a culture medium. The culture media are industrially produced, highly complex mixtures of fats, proteins, hormones, vitamins, signaling molecules, and growth factors. The latter were often obtained from the umbilical cord blood of bovine embryos. Because their extraction is questionable, they now come from genetically modified microorganisms or from plants or algae.2

This is how meat is “grown” from individual animal cells. Over 100 companies worldwide are conducting research into laboratory meat.3 In Singapore, the first laboratory chicken meat is on the market. It was also approved in the USA in 2023. In addition to meat, other animal products, such as milk and fish, are also produced in the laboratory. “Sustainable, resource-saving, beneficial to animal welfare, safe”: the products are advertised with promising claims.

Scarce and Incomplete Data

Because methane, a byproduct of raising livestock, is many times more harmful to the climate than carbon dioxide (CO2), its reduction is cited as an important advantage of lab-grown meat compared to conventional livestock farming. However, a study by Chriki et al. (2022), asking whether lab-grown meat is an alternative to slaughtering animals, shows that this argument has not been sufficiently investigated.4 Cell-cultured meat might help to avoid global warming in the short term because no methane is produced. In the long term, however, it could be even more harmful because the carbon dioxide produced during the production process remains in the atmosphere longer.5

The production of laboratory meat is still not taking place in enough quantities for meaningful data to be collected. For example, the first beef burger from the laboratory cost 250,000 euros.6 Furthermore, it is not transparent what the life cycle of laboratory meat looks like or if industrial production of the nutrient medium is included in the calculations. The production of 1 kilogram of beef requires approx. 550 liters of water compared to up to 521 liters for 1 kilogram of laboratory meat.7 The water footprint is, therefore, similarly high. In addition, the production of laboratory meat takes a lot of energy. Comparable figures are not yet available. In terms of land requirements, it is obvious that lab-grown meat requires less land. However, the review states that the importance of animal husbandry for the environment, landscape conservation, and soil fertility should be taken into account in this comparison.8 The argument that laboratory meat is more animal-friendly should also be viewed critically. How are the animals that act as stem cell donors treated?

What Cows Give to a Farm

In biodynamic agriculture, the animal, especially the cow, is an integral part of the farm. They eat feed grown on the farm and not only provide valuable food but also high-quality fertilizer—their composted manure is the basis for soil fertility. Animal husbandry is also soil-based. This means that the number of animals is adapted to the land and not to the capacity of the barn. Only as many animals are kept as the farm can feed. This eliminates the need to import feed. At the same time, only as much manure is produced as the soil can absorb and convert. In such a cycle, everything is recycled in the best possible way.9 The welfare of the animals and the health of the soil are paramount.

All of this has a positive effect on the quality of the food. It reflects the animal husbandry and health, but also the feeding, plant cultivation, and the farm, with its people, as a whole. Such products nourish and stimulate the senses. Food from the laboratory, on the other hand, has no history. It is grown in an environment without any natural external stimuli and always has consistent ingredients. If we eat mindfully and train our senses, we can perceive the different effects of food. According to studies, the taste of a laboratory product is similar to that of an average natural product, but how does it really affect us, beyond the taste?

What Diversity Means

Manufactured, in vitro products are produced in a fully controlled environment and are therefore promoted as “safe,” meaning they are free from any contaminants and pathogens. Only nutrients that are known are added. The biological diversity and the countless combinations of substances that occur in nature are not contained within these products. Instead, products are created that consist only of isolated substances. This type of food production is based on the assumption that food only contains nutrients and, above all, that only nutrients nourish us. If we look to the future with this assumption, we can imagine a diet consisting of a synthetic uniform mash that is pressed into desired shapes using a 3D printer. Do we really want to go without the variety of colors, shapes, and flavors of real food, with their own biography and character?

A Living Environment for Living Food

If we do not reduce food to its ingredients but consider its full potential to stimulate us, it becomes clear that a living environment is needed for healthy food to develop. The relationship between nature, animals, and humans is cultivated in organic and biodynamic agriculture. People are actively involved in shaping this relationship, for example, through their choice of food. When we buy meat from factory-farmed animals, we are saying yes to this form of husbandry. In the same way, we are saying yes to alienation from the living when we support laboratory meat. The question of whether our food will come from a laboratory in the future is not just a question of food production but of our fundamental attitude towards nature, plants, animals, and, ultimately, ourselves. Do we want to move further and further away, or do we see ourselves as part of the whole to which we are connected and want to be connected?

Translation Laura Liska

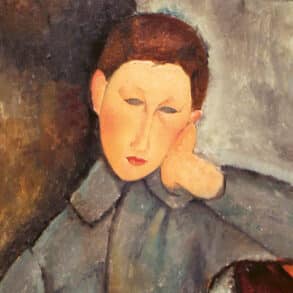

Photo The Meat Revolution, Mark Post. First cultured hamburger, unfried. Source: commons.wikimedia.org

Footnotes

- Fleisch aus Zellkultur kommt auf den Markt [Meat from cell culture comes onto the market], March 2024.

- G. Willinger, “Fleisch aus der Retorte” [Meat from the test tube] Spektrum der Wissenschaft 4, 2024, Pages 44–49.

- Fleisch aus Zellkultur kommt auf den Markt [Meat from cell culture comes onto the market], March 2024.

- S. Chriki, M. P. Ellies-Oury, J. F. Hocquette, Is “cultured meat” a viable alternative to slaughtering animals and a good comprise between animal welfare and human expectations? Animal Frontiers, Volume 12, Issue 1, February 2022, Pages 35–42.

- Ibid.

- Fleisch aus Zellkultur kommt auf den Markt [Meat from cell culture comes onto the market], March 2024.

- S. Chriki, M. P. Ellies-Oury, J. F. Hocquette, Is “cultured meat” a viable alternative to slaughtering animals and a good comprise between animal welfare and human expectations? Animal Frontiers, Volume 12, Issue 1, February 2022, Pages 35–42.

- Ibid.

- L. Maschek, “Kuh und Klima—eine Frage der Haltung” [Cows and climate—a question of attitude] Fonds Goetheanum, October 2023.