What is the relationship between biodynamic agriculture and the indigenous peoples’ understanding of nature? What can be learned here? Jean-Michel Florin, co-director of the Section for Agriculture at the Goetheanum, shares his thoughts.

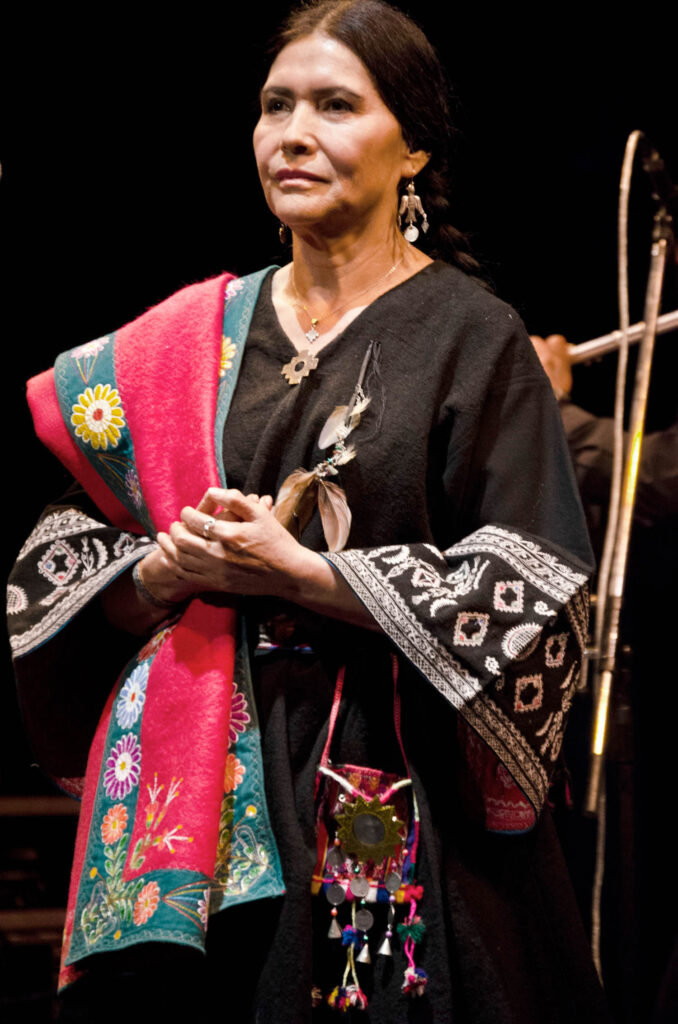

A few years ago I had an encounter with Luzmila Carpio, a famous singer from the Quechua people of Bolivia. She was, for a time – under the government of Evo Morales – UNESCO Ambassador of Bolivia. An acquaintance recommended a record of her to my wife.1 The music had really touched us. A few weeks later I was invited to a biodynamic farm in the South of France. In the evening I went to an eco-festival and was asked by my hosts to take her friend from Bolivia. While driving, we exchanged ideas, and suddenly I noticed: Next to me sits the woman whose voice impressed me so much. That’s how you get to know each other! Later she told us that when she heard the birds sing, her mother knew that a guest would come in the evening: a self-evident life with the ‹invisible›. We noted further similarities between the biodynamic approach and the Quechua tradition, starting with the fact that both see the Earth as a living being.

We wondered what kind of relationship we could establish between biodynamic agriculture born in Europe and the cosmological tradition of the Quechua. Each current might need the other. Luzmila told us that young people no longer cultivate their traditions, long for modernity, and throw away all spiritual foundations. Meeting people who practice spiritual agriculture in Europe in a ‹modern way› could encourage young people to take their traditions seriously. And we, as biodynamic Europeans, can gain more legitimacy for our search for a spiritual approach to agriculture through the tradition and growing recognition of indigenous peoples. On other occasions, I had also noticed that in many countries of the world, such as India, Togo, or Argentina, farmers who are closely connected to the earth long for a connection to their tradition and for a spiritualization of their work. How can we learn from each other? For this reason, we had for the Agricultural Conference 2020 ‹Ways to the Spiritual in Agriculture›2 Representatives of indigenous peoples from all over the world were invited.

Who are the indigenous peoples?

In the stream of decolonization and emancipation movements, indigenous peoples assert themselves and seek recognition. They not only want to be tolerated or seen as interesting research topics for ethnology but really want to be taken seriously. To this end, its representatives actively participate in all major meetings, such as the recent Nature Congress in Marseille (UICN).3 Or at the COP 26 climate conference in Glasgow, where Diaz Mirabal (member of the Wakuenai Kurripaco tribe) represented the indigenous peoples of Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana and said at the press conference: «We are at COP 26 to have our proposal ratified to keep 80 percent of the Amazon alive. We are the Amazon for life, we are the cry of the air, the water, the creatures of the forest, we are here to get answers and action from the states.»4

They represent about 6.2 percent of the world’s population and maintain 80 percent of the world’s biodiversity. They inhabit 25 percent of the global land area. Many agricultural practices on Earth have their origins in indigenous agriculture. It has now been proven that they have cultivated almost the entire earth for more than 10,000 years.5, contrary to the general colonialist opinion, indigenous peoples such as the Aborigines have stopped at the stage of hunting and gathering. They did it in very different ways. Sometimes as gentle as in the Amazon forest, where researchers recently discovered that the so-called untouched primeval forest with the greatest biodiversity is a cultivated forest.

Researcher Julia Wright from the University of Coventry6 had presented further connections between biodynamics and indigenous traditions during the last research conference of the Agricultural Section at the Goetheanum: In a joint action7 16 representatives of indigenous peoples called on the movements of organic agriculture not simply to take these practices out of context, but rather to deepen the worldviews from which they originate, which respect living beings. They went on to explain that only a changed perspective can lead to the radical change of attitude that our time so desperately needs. In their appeal, these 16 representatives presented philosophical concepts that lie across their various cosmogonies. A remarkable achievement! The main aspects of the indigenous appeal can be summarized in the following six points: 1. Affirmation of the unity of human beings and nature against the modern view of the duality of human beings and nature. 2. Affirming that everything is alive instead of separating dead and living elements. 3. Reaffirming the constant search for balance instead of explaining the world with the dualism of good and evil. 4. Reaffirming the need for linguistic diversity in order to preserve the extraordinary diversity of reality in every place, given the exclusive supremacy of the English language. 8 5. Claim that human beings belong to the earth and not the earth to human beings. 6. Claim that the earth goes through cycles of change and that death brings new life, rather than the claim that the dying earth must be saved by us.

Common Roots

If you compare these basic concepts with the anthroposophical or biodynamic understanding of the relationship between human beings and earth, as Julia Wright does, you will find many exciting similarities. Is this relationship so amazing? Doesn’t this substance, this knowledge, come from the same origin? Rudolf Steiner always pointed out that he had not invented anything, but had observed in the spiritual world with a scientific method. The indigenous peoples had and have also maintained contact with this spiritual wisdom. There are more similarities than one would think. That speaks for a rapprochement. The most important similarity is that one works with the ‹hidden half of nature› and not only with the physically visible one. Various sociologists and anthropologists have studied the biodynamic practices and the worldview behind them. Most of the time they take as a basis the work of the ethnologist Philippe Descola9, who lived with the Achuar in South America. He tried to understand their worldview and developed a theory based on four different ontologies (notions of being in the relationship between human beings and nature): animism, totemism, analogism, and naturalism. He showed that our civilization today is based on naturalism. His hypothesis is that on one hand there is the human being who lives in closed societies, and on the other hand there is something foreign: nature. Nature is everything that is outside, that can be used and exploited, hiked, or even protected. But it’s not the place where you live. Human beings are not part of nature. Naturalism created the duality of human beings-nature. Descola shows that the other three ontologies do not make a strict separation between human beings and nature, which is why they have a less destructive effect on living beings than naturalism. In his study, Jean Foyer shows,10 that biodynamics is not only naturalistic but also sometimes animistic or analog when talking to animals and plants. These terms, which sometimes seem schematic, help researchers to understand biodynamic practices in their mental context. And so the indigenous peoples indirectly help to understand our biodynamic approach.

Consequences

The call of the indigenous peoples shows in a very efficient way how one can present one’s otherwise only implicit worldview. It became clear how biodynamic agriculture or other organic farming practices should clearly present their ‹worldview› in order to avoid being seen as incomprehensible without context. It is difficult to understand certain ‹strange› practices and methods, such as the biodynamic preparations of horn manure and horn silica, without their context. Moreover, this call makes it clear that applying a method without its underlying mindset will not have much effect in the long run. He also shows that in our culture we should examine and acknowledge our roots more closely in order to tie our current way of life more closely to the past and thus go better into the future.

As a final consequence, you can discover a new task. Is it not urgently necessary to exchange ideas with the representatives of indigenous peoples all over the world? In order to deepen one’s own traditions and to avoid that biodynamic agriculture, which has its origin in the European tradition, has a colonialist effect. Some biodynamic friends in different countries have already started with this.

Footnotes

- Luzmila Carpio, Le chant de la terre et des étoiles (Une création inspirée par le grand livre des Indiens quechua). Harmonia Mundi, 2003

- Documentation of the Agricultural Conference 2020. www.sektion-landwirtschaft.org/lwt/2020

- Conclusion Congrès uicn 2021. https://uicn.fr/congres-de-luicn-bilan/

- ‹Le Figaro›, 10/30/2021. https://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/cop26-les-peuples-autochtones-plaident-pour-la-preservation-de-80-de-l-amazonie-20211030

- People have shaped most of terrestrial nature for at least 12,000 years. https://www.pnas.org/content/118/17/e2023483118

- J. Wright, N. Parrott (Hg.), Subtle Agroecologies – Farming with the Hidden Half of Nature. Taylorfrancis.com (http://taylorfrancis.com/). 2021

- Whitewashed Hope. 2020. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/whitewashed-hope-message-10-indigenous-leaders-and-organizations

- See footnote 6.

- Philippe Descola, Par-delà nature et culture. Gallimard, 2005

- Jean Foyer. https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/241712

In N.Z. we have the Maori traditions but there are more ancient stories of the Maoriori before them. We don’t hear much about the latter as they were practically all but wiped out.