For the first time, the United Nations has placed mental health on par with major chronic diseases like cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions.

In the new resolution presented at the General Assembly in autumn 2025, the UN called on member states to integrate mental health into primary care, aiming to ensure 150 million more people have access to mental health services by 2030. This shift signals a historic turning point! Mental health is no longer considered a separate sphere but an integral component of physical health. Yet, as in every great political equation, there is a point where we lose sight of what makes us human—and that is where the shadow of this otherwise welcome development begins.

From the Soul as Symptom to the Soul as Parameter

The new international political rationale treats mental health as a “risk factor” for chronic diseases. Depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders are condensed into measurable data—placed on the same level as blood pressure and cholesterol. The intention is extremely valuable and humane; no one questions the need for broader care. But behind the language of care, a new kind of psycho-administration begins to emerge: the inner life of the human being becomes a field for regulatory management. Rudolf Steiner repeatedly emphasized that the human soul is neither a machine nor an organ—it is the space where the spirit gains experience within matter. When the soul becomes merely a “field of intervention,” it loses its nature as bearer of meaning. Then we no longer have care but surveillance; no longer healing but the standardization of inner life.

A Psychology Without Spirit!

In his lectures on psychology and psychoanalysis, Steiner offered perspectives that today sound strikingly prophetic. He noted that when psychology detaches itself from the spiritual dimension, it loses its therapeutic capacity and begins instead to shape the soul according to the dominant instincts of the age. Psychoanalysis, he observed, tended to draw the spiritual life downward toward the unconscious; today, the risk is that it may sink even further—toward algorithms, data categories, and administrative protocols. If “mental health care” becomes a bureaucratic duty of states, the spiritual element of the human being risks being extinguished in the statistical uniformity of systems. Anthroposophic medicine does not regard mental health merely as a balance of biochemistry or as a measurable “emotional performance,” but as a rhythm between the four members of human existence. True healing begins when the soul rediscovers its rhythm between biology and consciousness. There is no protocol that can impose that.

From Care to Normalization

Integrating mental health into primary care also raises legal and ethical questions. If the family doctor becomes obliged to “assess” a person’s mental condition, what does this mean for individual freedom? If mental health data are incorporated into patients’ electronic medical records, who will have access to them? And if international guidelines define a “standard of mental balance,” how will the diversity of the human soul be safeguarded against the normative claims of health policy?

Steiner reminds us that the human being is not a phenomenon to be observed but a being to be accompanied. When we try to “correct” a person, we lose them. The soul, in the anthroposophic sense, does not need control—it needs understanding. Mental illness is not a “system error,” but a call toward a deeper meaning that has been cut off. A medicine that wishes to remain truly human must be able to recognize that call, not only the symptoms.

From the perspective of anthroposophic medicine, the most important issue raised by the UN’s new policy is not access but freedom. Mental health cannot become an obligation, nor can it be legislated. Every soul has the right to walk its own rhythm between illness and transformation. Politics can organize systems of care; it cannot define what mental balance is without violating the uniqueness of the human being.

Anthroposophic medicine sees in mental suffering not only pain but also potential—the potential for a new form of awareness to be born. And such renewal, as Steiner often suggested, cannot be imposed from outside; it must awaken from within.

The new global narrative on mental health is undoubtedly welcome in its intention of care. Yet wherever spirit is absent, every good intention risks turning into a mechanism. The true challenge of the coming years will not be access but authorship—who defines the soul. And this is precisely where anthroposophic medicine, with its understanding of the human being as a threefold and fourfold entity, has something essential to remind us: health is not compliance but relationship—and freedom is not a luxury of the soul but the very precondition of healing.

References

- Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophy, Psychosophy, Pneumatosophy, GA 115

- Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophy and Psychoanalysis, GA 178

- Rudolf Steiner, Hidden Soul Powers, GA 143

- Rudolf Steiner, Connections Between Organic Processes and the Mental Life of Man, GA 205

- Matthias Girke, “It Is the Spirit That Builds Its Body—The Effectiveness of the Ego Organization in the Human Body,” Das Goetheanum Weekly, 2023.

- World Health Organization, “World leaders show strong support for political declaration on noncommunicable diseases and mental health,” 26 September 2025

- World Health Organization, “Fourth High-level Meeting of the UN General Assembly on the prevention and control of NCDs and the promotion of mental health and wellbeing,” 25 September 2025

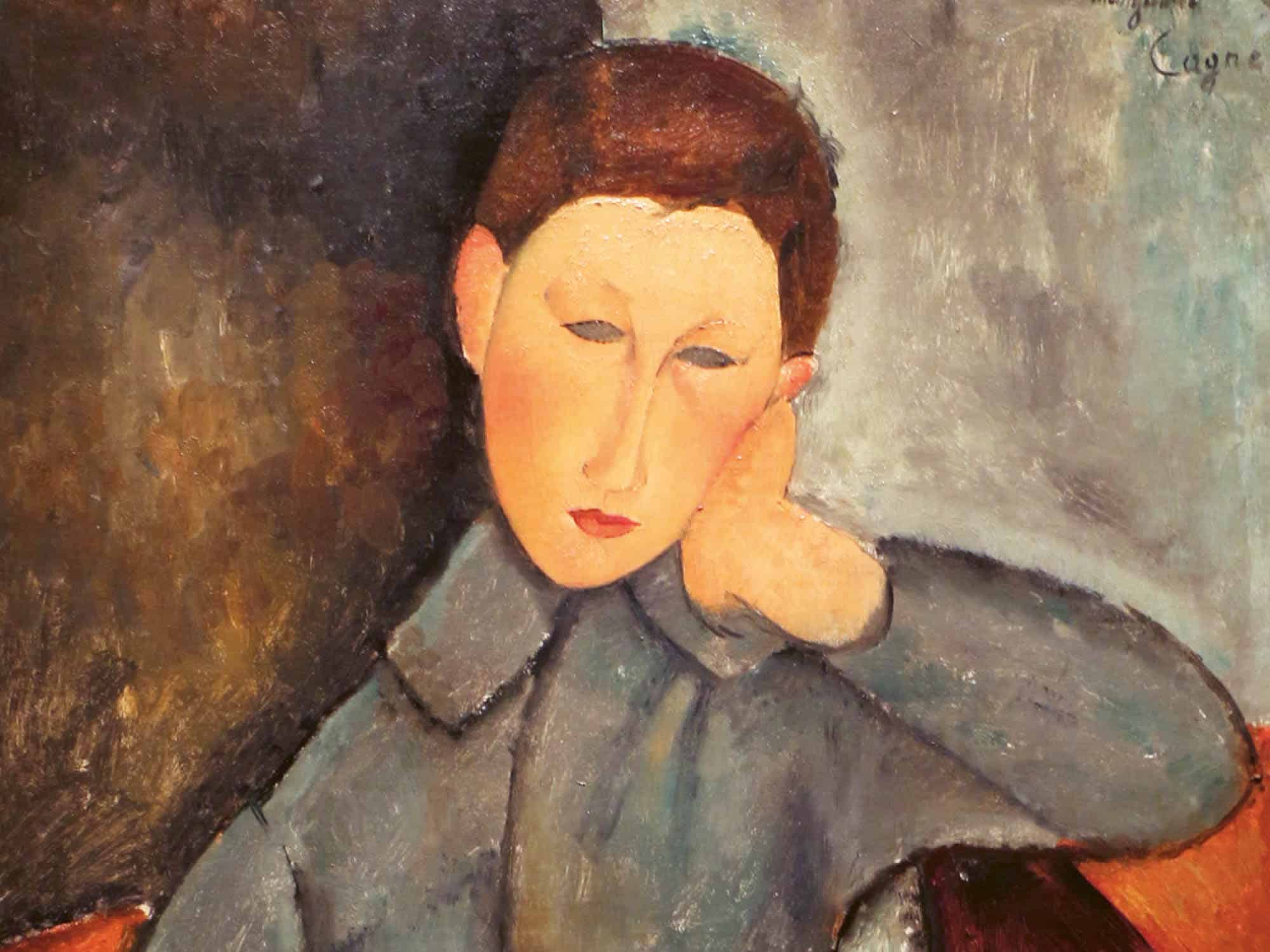

Image Amedeo Modigliani, ‹Il ragazzo› [The Boy] (detail), 1919. Photo: Wikimedia