In his new book, Wolfgang Gädeke shines a light on the origins of the Christian Community. He deconstructs myths, organizes sources, and shows Rudolf Steiner’s formative role beyond mere consultation. At the same time, he traces Steiner’s path from free thinker to religious thinker.

In September 1922, the Christian Community was founded by 45 theologians, pastors, and students. Rudolf Steiner provided advice and support without being a co-founder himself. Still, his involvement was especially meaningful for him, as he later publicly acknowledged: “I myself must count among the highlights of my life what I experienced with these theologians in September 1922 in the small hall of the south wing [of the Goetheanum] (where the fire was later first discovered).”1

A detailed history of this founding event is now available. In over 1,200 pages, Wolfgang Gädeke describes the “drama of destiny” surrounding the emergence of the Christian Community. This level of detail is needed because of the complexity of the events, but also to clarify misunderstandings and refute the defamation against the Movement for Religious Renewal that arose from a “lack of need for the path of knowledge” for those “who are not yet strong enough to work with spiritual science” (Marie Steiner, 1923 and 1928). In the decades that followed, up to the present, Marie Steiner’s account led to the “unfortunate doctrine of the two paths to the spiritual world.” The founding priest Johannes Werner Klein even accused Marie Steiner of falsifying history because of this.

The Crucial Question

Christian Community priest Wolfgang Gädeke takes a more sober approach: in a meticulous, source-critical investigation, he presents all the documents and individual stages of the history leading up to a petition to Rudolf Steiner on May 22, 1921. Students Johannes Werner Klein, Gertrud Spörri, Ludwig Köhler, and Gottfried Husemann had formulated a question about religious life and church institutions that is now considered the founding document of the Christian Community. Gädeke repeatedly revisits the history of this “founding question” to point out, between 1916 and 1921, which of the early participants—when and where—had repeatedly failed to ask Rudolf Steiner this “decisive question.” As if one merely had to ask and “the Doctor” would have instantly produced the desired information like some automated answer machine. As if Steiner would not have taken any action on his own initiative. Let’s not forget, he’d already described the Catholic funeral ritual as “far too feeble” to the Old Catholic Hugo Schuster in 1918 and had subsequently spoke of the need to renew religious life, and formulated and handed down new rituals. Gädeke attributes these facts to the beginnings of the Christian Community.

Rudolf Steiner’s Path to Christianity

In the first chapter, in one hundred fascinating pages, the author takes a step back and describes Steiner’s path to Christianity and religion, sincerely and without embellishment. For example, he courageously emphasizes and documents the incompatibility of Steiner’s early free-thinking positions of the 1880s and ‘90s with his later esoteric views. It is a journey through Steiner’s entire written and spoken work from the perspective of the development of his religious understanding—a journey that reads almost like an introduction to Steiner’s spiritual development in general. In doing so, Gädeke acts as an advocate for religious life and defends it against the purely intellectual approach of spiritual scientific meditation. For him, religious life is “underexposed” in the anthroposophical movement.

The further background also includes biographical sketches of the founding figures (Friedrich Rittelmeyer, Christian Geyer, Emil Bock, Rudolf Meyer, Johannes Werner Klein, Gertrud Spörri, and Hermann Heisler), which the author vividly presents in historical miniatures. The sometimes-naive enthusiasm of this founding generation is striking. Those of us born later, who have experienced the ups and downs of the anthroposophical movement, may be surprised by the terminological certainty and ideological conviction with which they approached the movement at that time. For example, certain participants in the first theology course were referred to in a list compiled for Steiner as “anthroposophists” (meaning members of the Anthroposophical Society), and concerns about possible social tensions and ideological differences were simply dismissed with reference to the Philosophy of Freedom and “free spiritual life.”

Generational Conflict

Among the founders, a simmering conflict existed between the young, who were eager to take action, and the older, more cautious members. The first theological course (June 1921) was launched by eighteen students who insisted that the upper age limit should be thirty. This could not be held to in the long run since the participation of renowned Protestant pastors Rittelmeyer (49) and Geyer (59) was wanted.

For the second theological course (autumn 1921), 107 people participated, including 28 pastors (almost all Protestant, one Catholic, and one Old Catholic) and 32 theology students. It also included six women, which Steiner considered egalitarian and a matter of course from the outset. (Bock was less relaxed about this throughout his life.) On the registration form, the participants declared that they felt the drive “to collaborate in the revival of new religious life in order to overcome the forces of decline in the present day and to achieve this goal in a new synthesis of cultus and Christian teaching.”

Christian Geyer’s Rejection

Gädeke also gives a detailed and vivid account of the year between the second theology course and the founding of the Christian Community in the fall of 1922. It was filled with the public commitment of individual participants to the new movement and efforts to establish congregations throughout Germany. This year was notably marked by Christian Geyer’s struggle. Together with Rittelmeyer and Bock, he had been designated by Steiner for the three-person leadership “in harmony with the spiritual worlds.” But the “incorrigible Protestant”—as Rittelmeyer described his friend—was thoroughly dissociated with the cultic rituals and struggled with his decision for or against joining.

Though he was closely connected to Steiner and anthroposophy and considered it possible that the rituals had been received from the higher world, despite all his inward openness, he did not feel the “breath of the spirit of Pentecost.” He confessed to Rittelmeyer and later to Steiner: “Something oppressive stands in the way: you must not do this!” The theological background to his refusal was probably that he could not reconcile his theologia crucis and religion of grace with what he considered to be the Catholic theologia gloriae and the Christian Community’s claim to sanctification.2 This refusal had an essential impact on the birth and development of the Christian Community. According to Gädeke, Geyer, with his healthy, cheerful character, would have been “a wonderful complement to the serious, infirm mystic Rittelmeyer and the forward-pushing, strong-willed Bock.” Thus, the preparatory meeting in Breitbrunn shortly thereafter and ultimately the founding of the Christian Community in September 1922 in Dornach had to take place without this renowned theologian and preacher.

Rudolf Steiner’s Involvement

Gädeke describes in detail how Steiner was involved in the birth of the Christian Community through the ordination of priests and the first performance of the Act of Consecration of Man.

Steiner initially performed only a demonstration of the Act of Consecration of Man in his civilian clothes. Afterwards, he himself officially performed some cultic acts: he blessed the altarpieces, lit the candles, and blessed the priests with gestures and words. At the very first consecration, Steiner placed the stole on Friedrich Rittelmeyer, clothed him in the chasuble, anointed him with oil, and spoke the words of commissioning while laying his hands on him. Gädeke describes this as a “Mosaic act,” since Steiner, “as a non-priest, performed on Rittelmeyer what Moses, as a prophet, performed on his brother Aaron.” This took place without reference to “apostolic succession,” which asserts the validity of ordination through an unbroken line back to the apostles. Steiner emphasized that the ordination ceremony was “received directly from the spiritual world” and that external succession was therefore no longer necessary. While Rittelmeyer then performed the first complete human ordination ceremony, Steiner stood next to the altar facing the congregation and also intervened in the proceedings with his hand and words. All this was far more than just an “advisory” activity, as is commonly attributed to Rudolf Steiner and as Steiner himself described it. Even in personnel matters (priestly consecrations, senior leaders, arch-leaders), Steiner did not merely act in an advisory capacity but played a decisive role.

A Difficult Social Relationship

A central focus of the book is the relationship between the Christian Community and the Anthroposophical Society, which was unclear from the outset and had led to dramatic situations just a few months after the founding of the Movement for Religious Renewal. Branches under the direction of their leadership took part in the Act of Consecration of Man en masse, with many now considering this cultus to be the “crown” of anthroposophy. There were resignations from the Society and transfers to the Christian Community, so that Steiner felt compelled to bring the anthroposophists back into line with harsh words on December 30, 1922 (the eve of the night of the fire!) This lecture then caused a great deal of confusion (which continues to this day), and Steiner had to mend the rifts in further lectures. He called the Christian Community a daughter movement of the Anthroposophical Movement and emphasized its legitimacy within spiritual life.

Although Wolfgang Gädeke writes as a priest with a naturally benevolent insider’s perspective, he nevertheless presents a consistent, source-critical, and never embellished account. It is rare to find in anthroposophical literature the willingness and ability to carefully distinguish and weigh contemporary sources, goal-oriented language, third-party reports, retrospective interpretations, etc. In an enormous research effort, the author has collected previously unknown material and evaluated it with admirable insight. This work serves as a model for anthroposophical research and journalism in terms of its methodology.

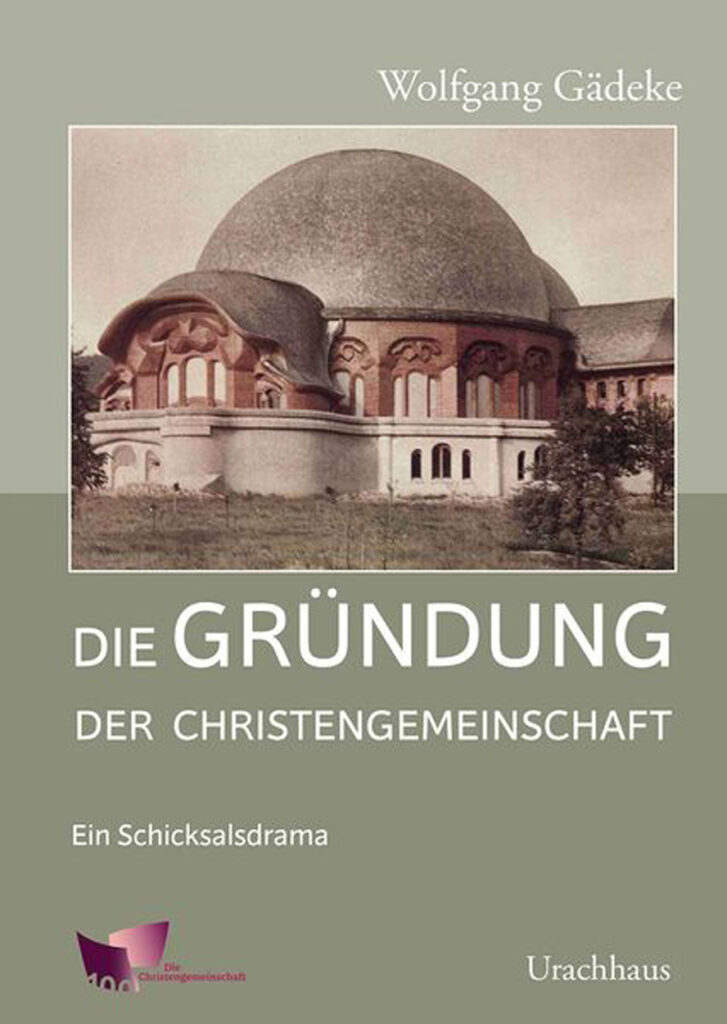

Book Wolfgang Gädeke, Die Gründung der Christengemeinschaft: Ein Schicksalsdrama [The founding of The Christian Community: A drama of destiny], two vols. (Stuttgart: Urachhaus, 2024).

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Rudolf Steiner, “Das Goetheanum in seinen zehn Jahren” [The Goetheanum in its ten years], part 7, Das Goetheanum 2, 32 (Mar. 18, 1923); in English, see Anthroposophy 2, no. 4 (Apr. 1923); today, in Der Goetheanumgedanke inmitten der Kulturkrisis der Gegenwart [The Goetheanum-thought in the midst of the cultural crisis of the present], GA 36, 2nd edn. (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2014).

- Theologia crucis, introduced by Luther, emphasizes that God reveals himself through the suffering of Christ on the cross and that salvation is given by grace alone through faith, apart from human merit, while theologia gloriae, rooted in Aquinas, emphasizes God’s glory revealed in creation and perfected in the beatific vision; salvation is attained through divine grace in cooperation with human virtue and reason—Translator’s note.

for much to long has the conundrum and questions about the relationship of Christian Community to Anthroposophy been avoided .. this work sounds like an exemplar guide to exposing and perhaps resolving the now century old conundrum of religion and it’s place in the Anthroposophy life .. definitely on my list of most wanted books/gifts for 2026!