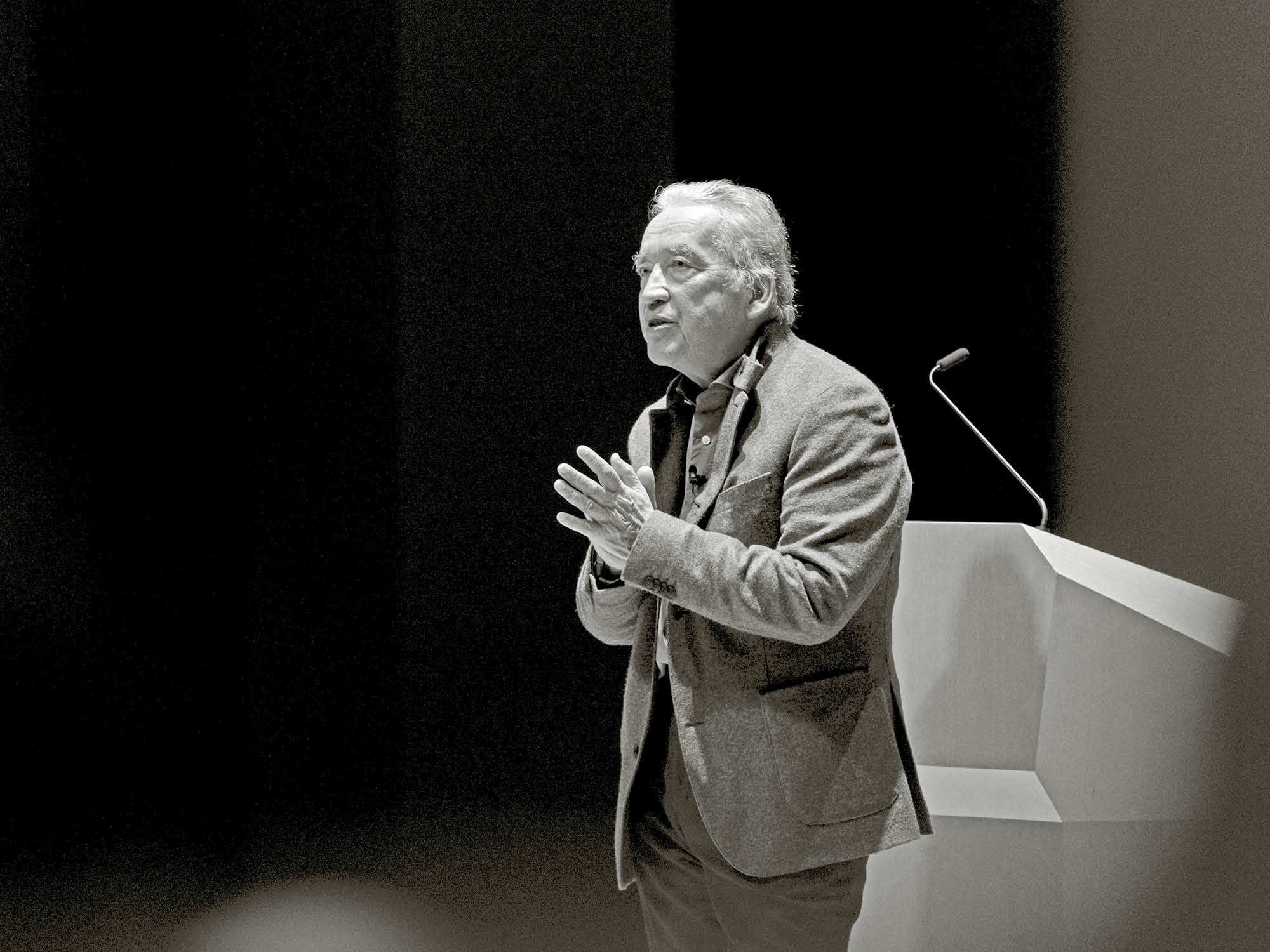

Ha Vinh Tho, September 27, 1951 – September 26, 2025

On the Friday before Michaelmas, Ha Vinh Tho crossed the threshold to the spiritual world. I received the news at the World Goetheanum Forum in Sekem, Egypt. The strong desire to bid a fitting farewell to this great master and good friend drew me from Egypt to Vevey on Lake Geneva, where he lay in state, close to his family. Tho’s physical body was reduced to the essential, and his expression was transpersonal. During life, facial expressions, emotions, and experiences are in the foreground, while after death, the timeless becomes visible. Standing before him, I never saw anything as clearly as I did then. Liveliness, compassion, warmth, strength, depth, clarity, and selflessness were all evident in his features. At the same time, I could sense that this was a person who had overcome distinctions and divisions to a great extent during his lifetime: the Tho now before me had features that were both masculine and feminine, both Eastern and Western. Would I describe Tho as masculine or feminine? Asian or European? He carried both Eastern and Western traits within him. He already lived largely beyond group identities bound to a particular place or people. Tho was a citizen of the world, as few others are. His life connected what usually is torn apart: East and West, inside and outside, I and you—but also, victim and perpetrator, friend and enemy, matter and spirit, vita activa and vita contemplativa, an active life and meditation.

When someone takes on the kinds of tasks that Tho took on, much depends on meeting the right people, such that “life” puts them in the right place at the right time and gives them the right tasks. Tho’s life contained many events of this kind, where a place, a person, or a new task opened a new chapter—so that something was created for him and for the world that would otherwise not have been possible. I’d like to share a bit of his biography.

Tho was born in France in 1951. His father came from Vietnam, the scene of a proxy war from 1955 to 1975 between the two superpowers, East and West, capitalism and communism, two polar views of humanity and society, facing off in merciless battles. His father was a diplomat. This allowed Tho to become familiar with different countries, cultures, ways of life, and ways of thinking at an early age. He received most of his school and university education in Paris, where he also earned a doctorate in educational sciences.

On a trip through Switzerland, he visited the Goetheanum in Dornach. He was fascinated and decided to study there. His attention was caught by the word “eurythmy” in some of the courses being offered. The word sounded promising, and he quickly decided on his study plan. He became a therapeutic eurythmist and worked in curative education, where he soon established and ran his own institutions. One day, he saw that the International Committee of the Red Cross was looking for new leadership for its International Academy. Tho applied and was accepted. The Red Cross sent him to areas of conflict and war: Darfur, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. There he witnessed immeasurable human suffering—but also the fascinating ability of human beings to unleash superhuman abilities to overcome even the greatest pain and hardship.

“I was in Pakistan in 2005 after the big earthquake. It was both the saddest and most encouraging time of my life. Many parents had lost their children because the earthquake happened during school hours. At the same time, people helped each other wherever they could. Even in the deepest distress, the people there still shared what they had. Since then, I have known what people are capable of. We can improve the world.”1

The Red Cross goes to areas of conflict, providing assistance in disasters, wars, and emergencies. They must be capable of empathy, helping, rescuing, and mediating—without taking sides, without losing themselves in pity, hatred, or despair. Tho helped thousands in humanitarian missions to find their way, to help, and to remain or become human in the face of evil.

Therapeutic eurythmy, curative education, and the Red Cross Academy: that could easily be enough for a full life devoted to humanity. But Thos’s path led him even further. He considered the system we live in today to be “unrealistic because it does not meet the needs of the majority of people and the planet.”2 Everywhere, the focus is on economic development, technological progress, and the pursuit of power and profit. Economic growth has become an end in itself. The Earth and humanity, meaning and climate, are suffering. Humanity must change its ways from the ground up if it wants to have a future.

Once again, a door opened for Tho in the historical development of humanity. He stood ready, able, and suited to take on the task at hand. Bhutan, the kingdom of the Himalayas, blessed with beauty and yet to be caught up in the sphere of influence of the superpowers, has chosen a different path than the rest of the world. Their focus is not on external, material growth (in monetary terms), but rather on the happiness of their people. Since the eighteenth century, the happiness of the population has been the primary goal of this country’s constitution. Their legal code of 1729 states, “If there is no law, happiness will not come to beings. If beings do not have happiness, there is no point in the [government].”3

The fourth king of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, decided to consistently focus on this goal. Gross national product (GNP), the benchmark (and fetish) of development, calculated every year in all countries around the world, was to give way to Gross National Happiness (GNH). He created an institute and sought out the right people. Their task was to discover how people’s happiness could be measured, evaluated, and, above all, increased. The worldwide search eventually led to Tho. He took up the leadership of the Gross National Happiness Center in Bhutan. This was a pioneering task of human dimensions. Bhutan did not stand alone for long. Shaken by the crises, contradictions, and catastrophes of their abstract, numerical development goals—and driven by protests from young people and a global civil society—more and more countries are now considering changing the standards and goals of their development. If social justice, peace, happiness, and cohesion, as well as responsibility for the climate and the Earth, are not to become the main goals of political and economic development, they will continue to be lacking. More and more countries are in the process of changing their constitutions, goals, standards, and indicators in this sense—though none as consistently as Bhutan. Tho developed criteria, standards, and instruments for placing external and internal development, harmony with oneself, with fellow human beings, and with the environment at the center of development. He was invited more and more often to become a global ambassador for this impulse.

Tho was an anthroposophist and a Buddhist—just as Ibrahim Abouleish, founder of SEKEM, was an anthroposophist and a Muslim. Both of them have demonstrated that anthroposophy is based on the realization of a genuine connection with spirit, making it compatible with any honestly lived religion. Tho cultivated this connection through daily meditation for over 56 years—and in this, too, he became an important teacher for many people.

Tho died on September 26, shortly before Michaelmas and his 74th birthday. He was a connector of worlds. In his being, his life, and his work, he connected what is otherwise always torn apart: East and West. Inside and outside. I and Thou. Earth, humanity, and spirit.

See also Ha Vinh Tho and Wolfgang Held, “Wie du glücklich wirst” [How to be happy], YouTube, 1:02:33, posted by Goetheanum (November 23, 2022).

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Image Ha Vinh Tho at the Agricultural Conference at the Goetheanum in 2024; Photo: Xue Li.

Footnotes

- Jan Petter, “Wir haben Bhutans Glücksminister gefragt, ob mehr Gehalt besser wäre als Yoga-Kurse: Kann man im Kapitalismus glücklich sein?” [We asked Bhutan’s Minister of Happiness whether a higher salary would be better than yoga classes: Can you be happy in capitalism?], interview with Ha Vinh Tho, Der Spiegel (March 20, 2018).

- Birgit Stratmann, “Es kommt selten vor, dass mich der Mut verlässt” [It is rare for me to lose my courage]. Interview with Ha Vinh Tho, Ethik Heute [Ethics today] (October 18, 2020).

- Michael Givel and Laura Gigueroa, “Early Happiness Policy as a Government Mission of Bhutan: A Survey of the Bhutanese Unwritten Constitution from 1619 to 1729,” Journal of Bhutan Studies 31, no. 1 (2014): 1–21.