Picture-forming methods like copper chloride crystallization, capillary dynamolysis, and round picture chromatography are now entering the era of computerized image analysis. Is this an opportunity to shape human spiritual evolution?

In our PhD work at the Society for Cancer Research, we use picture-forming analysis—a complementary research approach for quality investigation. There are several methods, but all of them create images with patterns and shapes that can be evaluated and analyzed to provide information about the quality of the tested sample. Lili Kolisko and Ehrenfried Pfeiffer were two pioneers of these methods, in collaboration with Rudolf Steiner. For Kolisko, Steiner suggested putting drops of the plant sap that she wanted to investigate on filter paper and studying the shapes that developed. She then developed the method further, mixing the sap with a metal reagent. For Pfeiffer, Steiner suggested observing the crystallization that took place when plant substance or blood was mixed with certain salts, in particular copper chloride.

Reaching the Neutral Ones

Why are we doing what we’re doing? Why are we trying to bring a concept as exotic as formative forces into contemporary science? I divide humankind into three groups: The “anthro-niche” are people who share our world perspective, are interested in the application of the research methods, and don’t need computerized image analysis data. The “unreachables” are those we hope to reach, but whatever scientific proof we come up with, it’s just not acceptable. And then the “neutrals”—the group we are really interested in. They may not share our worldview, but with solid science and communication about what we are doing inwardly, we believe we can reach them. Thomas Kuhn describes a paradigm as a set of assumptions, concepts, and methods that relate to how we perceive reality. There are multiple paradigms, but people in one paradigm cannot understand people from a different one. If we want to reach people in this neutral group, we have to adhere to methods that relate to their paradigm, so we use computerized image analysis as a means to objectify our results.

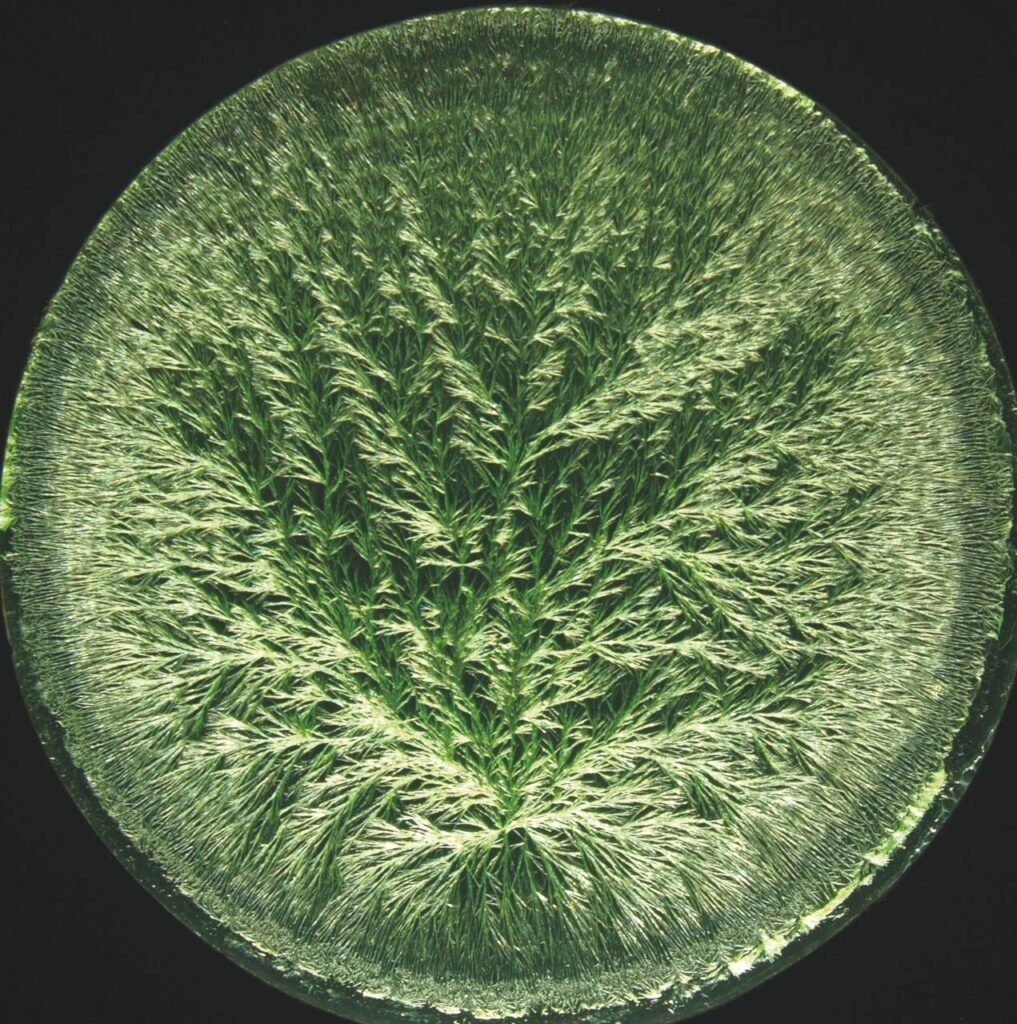

Crystallisation patterns of fresh (left) and aged 7 days (right) carrot juice showing a loss of organization and cohesion in aging.

Photo: Paul Doesburg.

Two Ways of Looking

As an example of how we really work, with copper chloride crystallization, we start with a human personal perspective. What are we trained to see in these beautiful pictures? In the crystal on the left, my attention is drawn immediately to the center where the crystal starts. The branches spread out nicely to the periphery. They are quite “fluffy,” by which I mean that they’re very full and rich with needles. I also see that the crystal is nicely organized: there is a hierarchical structure. If I compare this with the crystal on the right, I can still point to a center because I know that the crystallization probably started there, but it’s not that powerful—it’s not in charge of the whole crystal like in the other picture. Moreover, the branches are not very well defined: the needles are shorter and sometimes have gaps where I see a lot of background. It seems like there is less substance, even if it’s not the case. In general, I can say that, in my perception, we’ve got a more vital gesture in the left crystal and a weaker expression in the right crystal. These are carrot juice crystals: the top is fresh juice, and the bottom is about 7 days old. We can really see how it’s possible to describe the qualitative difference in degradation.

That was a qualitative description, using an empathetic approach—really living into the picture. It’s a clear characterization. You could argue it’s subjective, but we reached a level of intersubjectivity. You can understand the words and the limits that we used. Alternatively, we can look at the pictures from a computer perspective—what a computer algorithm would “see.” [computerized image of the crystal, full of small dots, is shown] With every dot, the algorithm can calculate the length of the needles and the space that the crystals or the background occupy. This would also give interesting results, and we would be able, in most cases, to discriminate between the two crystals. But this is computer “vision,” which means that we are converting a picture, a whole, into a binary code: 0110. The computer doesn’t know that there is anything else—it doesn’t know the context. With only the computer data, we would be completely lost because the unity, the sense of wholeness, is gone.

Finding a Middle Way

But of course, this perspective fits our present paradigm of looking with analytical perception. It’s very standardized and highly objective. We can repeat this countless times and get the same results. We cannot characterize the pictures, but we can group them: this is Group A, this is Group B, and they are more or less significantly different from each other. However, I don’t feel responsible when I present image analysis data. I can just show a graph. It’s not me. I did the research. This is the outcome. Two separate things. But when we talk about visual evaluation results, we really feel connected, really feel responsible. And that’s a fundamentally different attitude.

We might say that the first perspective expresses a more Luciferic impulse, the second a more Ahrimanic one. Our task is to try to balance the two and extrapolate the good qualities that both tendencies offer: the warmth and enthusiasm of the Luciferic impulse, but also the clarity of thought, the pinpointed attention, and the objectivity, as much as possible, of the Ahrimanic impulse. Our mission is to create a bridge for how to do that. First of all, we have to be aware that these two polarities exist in our science. Only then can we consciously embrace both impulses again, giving the right value to each of them. This is our way of bringing spirituality into modern science and our modern culture that is really falling, more and more, into Ahrimanic or materialistic tendencies.

In a talk that Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, the father of the crystallization method, had with Rudolf Steiner, he asked Steiner: how can we overcome the one-sided materialistic tendency we have in our present culture? This was 100 years ago. And Steiner answered that we must first acquaint ourselves with it and understand its views. Only then can we disprove it. “You have to take the bull by the horns and refute materialistic science by its own methods.”1

How Well Have We Done?

So, to what extent have we taken the bull by the horns? In 2001, we founded the so-called European Triangle cooperation based on three European laboratories with four identical crystallization chambers: the University of Kassel in Germany, the Louis Bolk Institute, and later Crystal Lab in Holland, and the Biodynamic Research Association Association in Denmark. We did some fairly revolutionary work in crystallization research. Adding the application of computerized image analysis to the visual evaluation was also new. We worked on the standardization and validation for a visual evaluation panel. One person in our group is deeply involved in unraveling the physics that contribute to picture formation—if you only show fantastic pictures but don’t have a clue how they arise or what their meaning is, you still have difficulty communicating your results.

How well have we done? We can judge this for ourselves by how well we sleep at night, perhaps, but also by how many articles we publish. To date, we have around 40 articles in peer-reviewed journals. We have standardized the crystallization method. We have a more in-depth physics underlying picture formation. In 2021, we published an article that compares which is more effective: an analytical visual evaluation method versus a kinesthetic method in which we empathize and perceive with our body something that we can see outside. (The kinesthetic engagement methodology was the most successful one.) We also formed a panel according to ISO standardization norms to score crystallization pictures. With this, we were able to very clearly communicate, in a scientific manner, the inner path we made from the picture to the qualitative interpretation. And in 2024 we published a handbook for the copper chloride system. There are only 90 printed copies, so it is a real collector’s item, but it is available as a PDF.2

We could hypothesize that, although we do use it for picture evaluation, artificial intelligence might be seen as a technical antithesis of our failure to develop imaginative consciousness with a large enough group of people worldwide. The steps we are taking are slowly going in this direction. Thank you very much.

This is a shortened and lightly edited version of the talk given at the conference.

More Natural Science Section: Evolving Science 2024 | Crystal Lab

Image Copper chloride crystallization method. Photo: Paul Doesburg

Footnotes

- Alla Selawry, Ehrenfried Pfeiffer: Pioneer of Spiritual Research and Practice, 1992.

- Handbook on the CuCl2 crystallization method.