“A hammer only sees nails.” This is a saying about the power of narrative. Moods guide perceptions, feelings seek a homeland, and judgments snap into place. In a complex world, narratives can be seductive. They become self-fulfilling prophecies, where one’s prevailing mood is confirmed and reinforces one’s worldview. There’s a widespread assumption that European societies are divided. Is that true?

Polarization is on the rise, so it’s purported, and in fact, the topic of “a divided society” is being mentioned seven times more frequently in German newspapers today than it was twenty years ago, with Brexit and the US elections being painted as scenarios that have also arrived in Middle Europe.1

Bactrian or Dromedary

In his book Triggerpunkte: Konsens und Konflikt in der Gegenwartsgesellschaft [Trigger Points: Consensus and Conflict in Contemporary Society],2 sociologist Steffen Mau examines whether this is true. Is our society polarized? Are individual groups and their worldviews becoming increasingly offensive towards each other? As an illustration, Mau uses a picture from zoology: Is the mood today like the back of a Bactrian camel, i.e., with two humps, a picture of two polar views, or does the back of the dromedary reflect the span of opinions, a clustered middle with a weaker border on the left and right? In order to find a meaningful view, Mau and his collaborators focused on long-standing conflicts, leaving aside debates such as the conflicts in the Middle East or the Russian war. On the basis of four scenes of conflict, four long-standing conflicts, “the conflict arenas of inequality,” as Mau calls them, the team investigated whether the divides are getting deeper: The top-bottom conflict—the dispute over the distribution of rich and poor; the inner-outer conflict—the dispute over belonging and foreignness, about the question of how open a society should be; the us-them conflict—the dispute over recognition, established mainstream versus outsiders; the today-tomorrow conflict—the dispute over climate change and resource consumption.

The Figures Say Otherwise

Steffen Mau’s research does not confirm the theoretical pictures that argue these four levels of conflict are tearing society apart. “Relatively little has changed over the last thirty years,” he says, summarizing his surveys on the migration debate, for example.3 A large majority of the population has a positive view of immigration. Surveys show that there has been an increase in the amount of people who accept Germany as a country welcoming immigration. Only around 20 to 25 percent of German society is critical in this regard. The real disagreement lies in how immigration is controlled and how integration is managed. The economic conflict does not lead to the formation of camps either. Although eighty percent of respondents complained about the enormous wealth gap in Germany, this doesn’t lead to protest. If it did, left-wing parties campaigning for justice would have the majority—but they don’t. According to the survey, this is less of a classic vertical conflict and more of a horizontal one.

Society has also become more liberal and more accepting of the other in the third arena, the dispute over recognition and exclusion. It was only 35 years ago that fifty percent of the population saw homosexuality as an illness, with the corresponding wish for exclusion. According to Mau, what has remained is the “tolerance of permissiveness”: everyone is allowed to be who they want to be, but they need not flaunt their differences. In the fourth arena, the today-tomorrow conflict, there is also no real polarization. Only around ten percent of society denies climate change. The vast majority see the need for more sustainability. There is no conflict of objectives but rather a conflict of procedures. The debate is not about if but about how. And, this doesn’t create a divide, but rather a diversity of viewpoints. Mau adds that these conflicts are no longer based on class, which means they’re not systemic. But then, how is it possible that we continue to have the impression that society is becoming more and more polarized? What do the pictures of angry demonstrators and violence against sign-bearing protestors and local politicians tell us if we’re not to see them as the manifestations of a society that is drifting apart?

Bike Paths in Peru

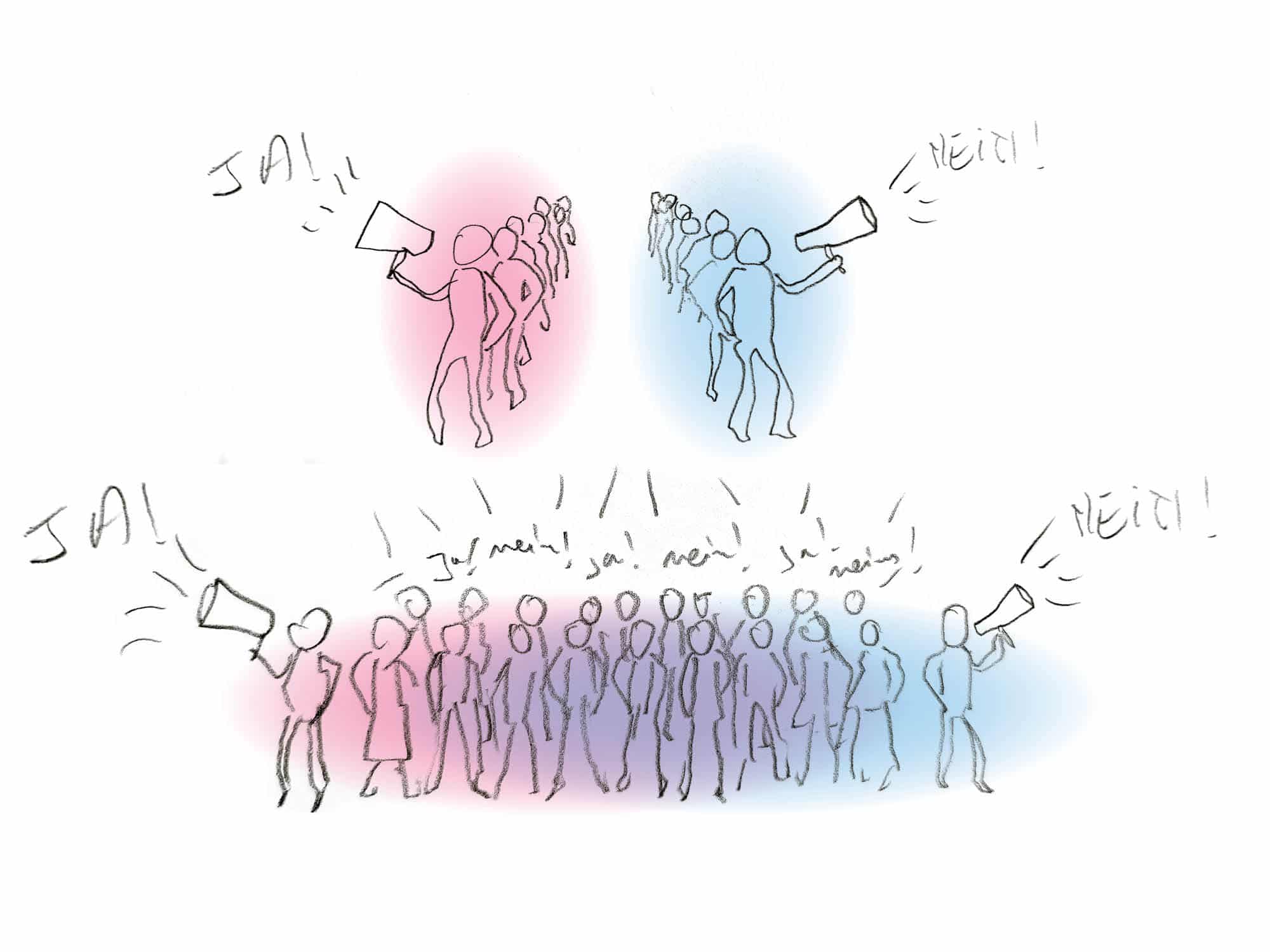

Recently, a politician claimed that rejected asylum seekers were being given dental treatments resulting in dentists without any available appointments for regular patients. What was the result? A media outcry. Another politician ranted about “bike paths in Peru” as a senseless form of aid. In an interview, a third politician called opposing parties “cartel parties,” referring to the Sicilian mafia or the Colombian drug syndicates. The use of such verbal transgressions and false statements is not without considered thought on the part of the speaker. These statements trigger wounds that exist in the population. They seize upon these painful areas, and the polarization becomes immediately present. “Division is not present in society, but it is created through politics and discourse. Division comes from above,” says Mau. He calls it a “management of trigger points by actors” that have created these opinion groups in the first place. Polarization through politicization. In this way, predetermined breaking points and areas of tension are used by politicians and the media with social media as its catalyst. In addition to the party leaders and media professionals who set the fires, there are those who turn the polarization of society into a business.

A Wounded Society

Mau recalls the campaign by Dortmund’s Zeche Zollern museum in the autumn of 2023, which advertised an exhibition on colonization with the slogan: “On Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., our white employees do not enter this building.” Instead of understanding the nod towards a kind of compensation, there was a tremendous outcry. Mainly people who had never heard of the museum and didn’t want to visit the exhibition in the first place were outraged. The museum ended up needing police protection. Society isn’t polarized; it’s wounded. Humiliation, lack of meaning, life plans lost after the fall of the Wall, and the arrogance of the West left millions of citizens wounded. Mau gives the diagnosis of “change exhaustion”—transformations that can’t be overcome with the previously learned ways of processing such things. What does a wound need? How does a wounded society heal? Conflict researcher Friedrich Glasl says that the first step towards peace is to turn cold conflicts into hot ones. The resentment must be brought to light; the wound must be opened. This has happened. Instead of criticizing the recent democratic deficit in European elections, there are some who point to the fact that the fire chief and the primary school teacher are now standing for election; they point to them without regard for their party affiliation but instead for the fact that they are getting involved in local communities, and getting elected. They see this as a departure from the status quo and towards what is needed: direct democratic co-determination. For this awakening to be fruitful, it will depend on how we learn to heal the wounds in our society.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Image Environmental Decision-Marketing in the Time of Polarization. Inspired by M. Judge et al. 2023.

Footnotes

- According to: Newspaper archive of the Digitalen Wörterbuchs der deutschen Sprache [Digital Dictionary of the German Speech].

- Steffen Mau, Thomas Lux, Linus Westheuser, Triggerpunkte: Konsens und Konflikt in der Gegenwartsgesellschaft [Trigger points: Consensus and Conflict in Contemporary Society] (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2024).

- Steffen Mau, “Wie polarisiert ist unsere Gesellschaft?” May 28, 2024, re:publica, 28:35 mins.