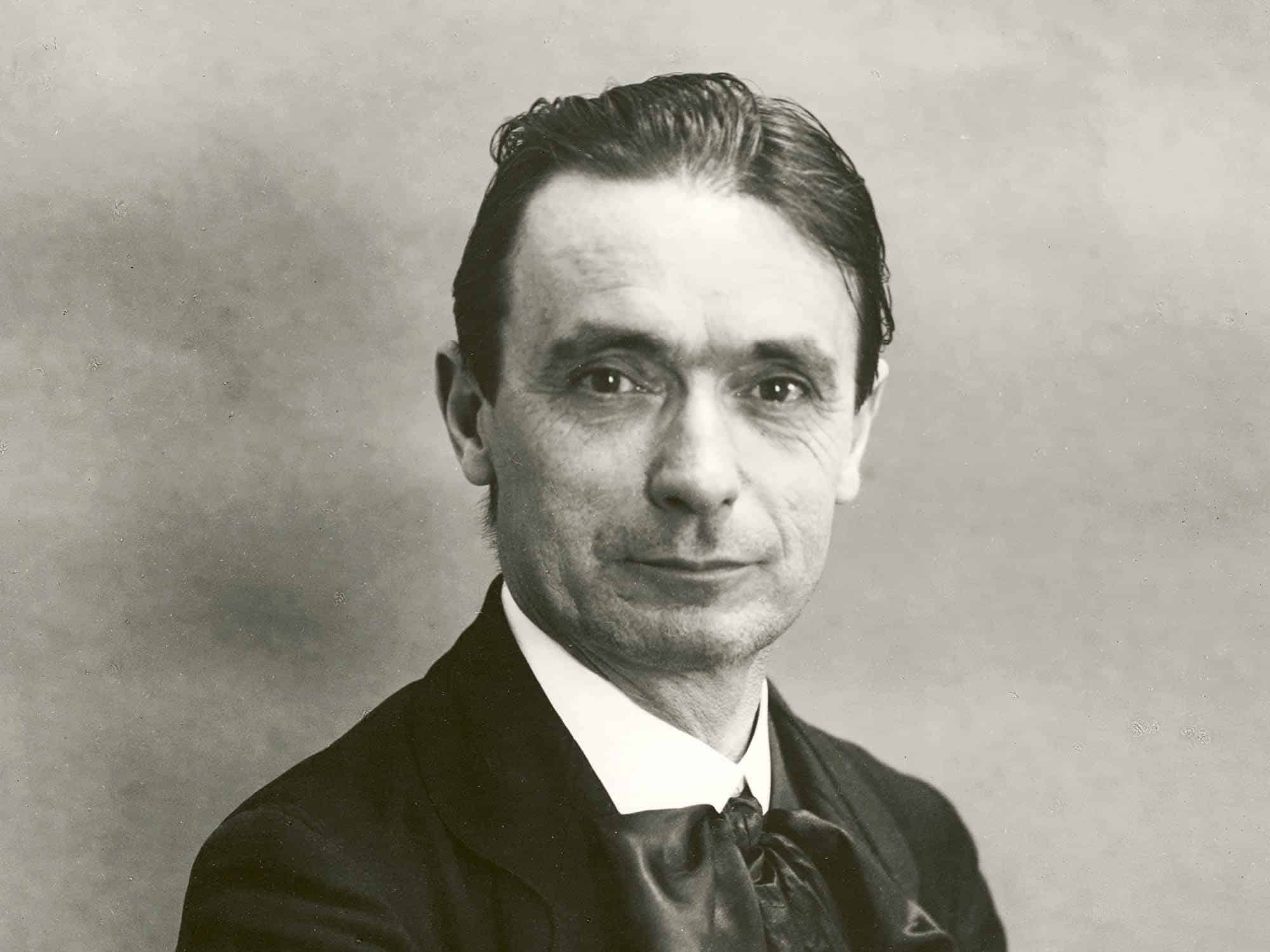

The centenary year marking the 100th anniversary of Rudolf Steiner’s death is now coming to an end. What will remain? Beyond all else, it is the personal encounters with Rudolf Steiner that endure. With this in mind, the journal Stil [Style] asked 27 individuals to address the question “Where do I find Rudolf Steiner?” and published their perspectives. Here is a selection from this bouquet of Rudolf Steiner in the present.

Rudolf Steiner was a guardian, a shepherd of time, writes Christine Gruwez. No period, no epoch was excluded from Steiner’s intimate listening. To encounter Rudolf Steiner is to encounter the abundance of time. According to Steiner, two mysteries play a special role in our development: death and evil. Steiner offers no consolation, no appeasement, no escape, but instead, he opens up a vertical and a horizontal understanding. The vertical means being able to grasp the high and the low. Understanding the horizontal means turning our gaze to the experience of time in its enigmatic double direction: into the future and from the future.

Wolf-Ulrich Klünker distinguishes between Rudolf Steiner’s personal accounts and his books. While the biographical accounts belong to his life that has passed, Steiner’s spiritual individuality continues to have an effect through his written works. The whole of Steiner’s ideas makes possible the emergence of the human individuality, not the other way around. Klünker also sees Steiner’s lectures as “preserved records of a moment in time” that bring the past into the mind’s attention in the present. In the sense of “like recognizes like,” Klünker takes three of Steiner’s characteristics as opportunities for encounter: he stands within the process of evolution, turns against scientific dogma, and integrates outside views into his own worldview. Encountering Steiner means practicing anthroposophy from this standpoint and attitude and overcoming an old form of relationship: “Only in a future-oriented perspective can a free view of human beings, their lives, and their further development unfold.”

Vesna Forštnerič Lesjak describes how she’s found Rudolf Steiner in human encounters. She considers Goetheanism, as a universal research method, to be the “best gateway to anthroposophy.” When she succeeds during a seminar at observing a plant in such a way that an encounter with the plant’s essence is experienced, then the support of her deceased teachers, Goethe and Steiner, manifests in the present. She concludes by saying that she encounters Steiner by listening to the questions of the times and putting her answers into practice.

Doctor Angela McCutcheon reflects on various moments in her life that she can trace back to Rudolf Steiner: her inspiring time in Waldorf school, conversations with her family, medical study groups, and discussions with patients. She wanders through her world of feelings: gratitude for her childhood, love of tradition, religiosity, reverence for nature, and a desire to learn. Here, she finds not so much Steiner himself but rather an abundance and depth of life.

The philosopher Eckart Förster also encounters Rudolf Steiner in his absence from academic discourse; Steiner is “silent, pensive, waiting” in the background. He experiences Steiner in the “liveliness that borders on the miraculous” contained in his spiritual science.

Historian Andre Bartoniczek, following Rudolf Steiner’s contemporary Hermann Friedmann, emphasizes Steiner’s ability to listen “with all his organs.” Friedmann says, “I believe he heard, saw, felt, and understood the speaking human being.” Bartoniczek underlines Rudolf Steiner’s ability “to speak out unreservedly and not remain in selfless withdrawal, but to throw himself out there passionately, to share his own insights, ideas, and impulses with those around him.” What lives in the soul as a contrast between receptivity and productivity is heightened in Steiner to polar opposites, while at the same time forming a whole. Bartoniczek takes Steiner’s engagement with Ernst Haeckel’s conceptions of social Darwinism to demonstrate how, by embracing ideas that are contrary to their own, those that are repressed can sometimes liberate themselves. For Steiner, it was “about the inward strength to endure what is repellent, to break away from the attachment to a deeply loved but bodily bound point of view.” Bartoniczek summarizes, “Where can I find Rudolf Steiner? In many outer and inward places—and also everywhere I encounter the effort to develop a certain strength, out of which a lived dialectic is able to arise, a capacity that offers healing for our social, collegial, and personal relationships and thereby for our future.”

Anna Katharina Dehmelt, who focuses on anthroposophical meditation, suspects that today more “inner, personal contribution is needed to ‘get to the bottom’ of anthroposophical study, as if the spirit that brought forth this work (anthroposophy) had withdrawn.” She senses Rudolf Steiner’s “formative force where spirit is imprinted in thought, ideal, and deed.”

Nana Göbel approaches the question of Rudolf Steiner with a broader question: “Have we the strength to nurture what is human—across all boundaries? Have we the strength to overcome our own prejudices?” Her search for Rudolf Steiner leads her to the following observation: Where something new comes into the world, and we become active—in ourselves, inwardly, and in a circle with others, outwardly—we find ourselves in harmony with the spiritual intentions of that entity who called himself Rudolf Steiner at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

Bastiaan Baan concludes with an aphorism and a dream: “Where and how do I find Rudolf Steiner? I come close to him through selfless love and enthusiasm for our cause—even when he is far away.” The dream: “He was sitting at the entrance to a hall where he was supposed to give a lecture. He had to sell the tickets himself. But I had no money. He looked at me intently and finally said, ‘You may go in.’”

Please note These excerpts are selective and taken out of context.

Full issue Visual Art Section of the Goetheanum, Stil, “27 Blicke—Wo ich Rudolf Steiner finde” [27 views—Where I find Rudolf Steiner] (Easter 2025).

More Visual Arts Section at the Goetheanum: News of the Section

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Image Rudolf Steiner. Photo: Otto Rietmann