Mehdi Ha’iri Yazdi investigated the ‘I’ and created a bridge between philosophy and religion through his thinking.

What is thinking? What is its purpose? What does thinking mean in the totality of human nature and in the whole plan of creation? Mehdi Ha’iri Yazdi (1923–1999) pursues these questions in a profound and independent way, distinct from what developed in the Western world since Descartes, mainly in discursive thinking. He was born in Iran and grew up in a family of highly educated academics and religious scholars, who were teachers of Shiite philosophy and theology. He received a classical education in philosophy, theology, and “Irfan” [“Islamic gnosis”] at the University of Qom, the most important center for this field of study. Later, he studied at the University of Tehran, where he obtained his doctorate in theology in 1952. He was likewise interested in Western epistemology and methods of science. For many years, he immersed himself in the work of Avicenna (980–1037), an all-around genius and polymath who was familiar with the Neoplatonic school, was himself a peripatetic, and wrote a “Summa” in the spirit of Aristotle’s metaphysics. Mehdi Yazdi studied texts by the mathematician and astronomer Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274) and by the inaugurator of the Persian philosophical Renaissance, Mullah Sadra (1571/2–1635/40). But Yazdi’s most important teacher, repeatedly encountered in all his writings, was Shihab al-Din Yahya ibn Habash Suhrawardi (1154–1191).

From the teachings of Zarathustra and the works of the Neoplatonic school, including the Peripatetics and Avicenna’s world of thought, Suhrawardi initiated a completely new beginning of Iranian thought, which he described as a sunrise. This was not a metaphor but rather a real experience: it is the light of thought that rises in the soul and not only illuminates it but also endows the soul with the creative faculty of knowledge. It is the presence of the spirit in the soul: thinking in the light of the spirit.

During his stay in Canada (Toronto) and the US (Michigan), Yazdi studied the works of Kant, Hegel, James, Russell, Wittgenstein, and others with the same passion as he did with those of the Persian philosophers in Iran. From this deep-rooted connection with Iran’s ancient tradition of thought, he immersed himself in the problems that were being discussed in Western epistemology at the time, in the hope that this would enable him to make a contribution to Islamic philosophy as a whole. In 1979, he returned to Iran, where he taught mainly at the University of Tehran until his death. In his work The Principles of Epistemology in Islamic Philosophy: Knowledge by Presence (1992), Yazdi developed the theme of “knowledge by presence” (al-‘ilm al-huduri). This concept did not originate with Yazdi, however, but rather with Suhrawardi, who was the first to use it.

Mehdi Yazdi was not the only Iranian philosopher of the twentieth century who continued his studies in the West or who was open to what was developing in the philosophy of the Western world. But, he was unique in making Western thought his own, to test it against the philosophical discourse that had developed in the Islamic world, and reciprocally, to make the thinking of the spirit visible to the light of discursive thought that has become so prevalent in the West in recent decades. Yazdi’s great theme was “knowledge in and by presence,” which presupposes a quite specific state of consciousness—namely, the rising of the light of thought in the soul.

Two Paths to Knowledge

Yazdi distinguishes between two forms of cognition: knowledge by correspondence and knowledge by presence. In order to establish the difference, Yazdi describes the thinking processes for these two forms phenomenologically. He was interested in the question of whether a form of thought exists in which the classical dichotomy of subject and object is no longer relevant. Yazdi’s first step in this direction was to describe what happens when someone says, “I think.” The ‘I’ that says, “I think,” and the ‘I’ that thinks are not two different entities; they are one and the same. I know from direct inner experience that this is so. One need not insert a proxy in this case, as if I first had to make a proxy for myself in order to come to the conclusion that I think. It is important to realize that we are dealing with a well-defined situation here, namely that of thinking!

This immediate inner knowledge (intuition) in the transparency of the act of knowledge itself is what Yazdi, without contradicting Suhrawardi, called “knowledge by presence.” The thinking process must, therefore, be described. Due to the deep intimacy he’d acquired over many years with the representatives of Western philosophy (Descartes, Hume, Kant, Hegel, and also Heidegger, Russell, Wittgenstein, Popper, and Habermas, with whom he entered into dialog in his work), Yazdi was able to lay open the characteristics of logical-discursive thinking in general and the separation of subject and object in particular, with great precision. On the other hand, as far as knowledge by presence is concerned, Yazdi could boast of being part of a centuries-old tradition in Iranian philosophy in which Avicenna, Suhrawardi, and Mullah Sadra not only laid the foundation stone for thinking in the light of the spirit but—and this is far more important—created a language that could be used as an instrument to express the individual moments of this thinking in its nature as a process.

The Triad of the Thinking Process

It is important to note that when Yazdi, following in the footsteps of his predecessors, described the thinking process, he always used the concept of a triad: the knower, the object of knowledge, and the thinking that, as an activity, builds a bridge between the two. In analytical knowledge (as in discursive thinking), the object of knowledge is external to the one who knows. Thinking must make use of representations that are already available. Truth arises when a correspondence is able to be shown between the representation and the object outside. This kind of knowledge has raised all kinds of questions about methodological certainty. Different points of view (Habermas, Popper, Russell) still define Western philosophy today in terms of a duality and separation of the knowing subject and the known object.

In “knowledge by presence,” the object of knowledge does not appear in a field other than that of the knower—in other words, that towards which the activity of thinking is directed appears in the same realm as that which performs the act of thinking. This process points to self-knowledge; however, this must not be confused with insight, in which the self is handled as an external element before the knower’s gaze and representations of the self must be made. Nor does the thinking human being become, so to speak, subject and object. It is not unio mystica! Yazdi has described the mystical experience and its translation (again, we see the great significance of language and its use) as a special form of “knowledge by presence.” But, in this second form of knowledge, the foundational pattern of the triad remains the preeminent characteristic. It is the dynamic between the three elements that makes knowledge into “knowledge by presence.”

Making the role of thinking transparent remains a necessary condition: neither self-analysis nor fusion but a fully awakened presence in the act of one’s self-thinking—which comes down to being present in oneself. It is a thinking that carries itself through the process of the act of thinking. Yazdi considers all other forms of knowledge, such as knowledge in which the object is an external factor, to be derived from this self-sustained thinking. And, while in “thinking by correspondence,” there always remains a factor of uncertainty that must be overcome by Cartesian doubt, Yazdi regards “knowledge by presence” as “living in the immediacy of truth.” Between the knower and the object of knowledge, there is no representation that must function as a bridge between subject and object. The knower and the object of knowledge are both of an identical “nature.” In the dynamics of the process of knowledge, this is reciprocally perceived, and it becomes an experience of “wholeness,” which can be compared to an experience of happiness.

Liberation

For discursive thinking, the division into subject and object is a prerequisite. It is this dualism between the knower and the object of knowledge that constitutes this thinking. That which I know (the subjective pole of the thinking process) and that which is known (the objective pole) must coincide, thereby offering certainty and leading to truth. Knowing by presence takes place outside of this dualism. It is beyond the partitioning into subject and object.

Yazdi describes this as liberation from the compulsion to generate proof, for this form of knowledge does not need proof in the nature of consensus. Proof is needed when the object of knowledge lies outside of me. Then, one needs a representation in order to internalize the object of knowledge. The principle of consensus then prevails as a criterion of truth or untruth. However, this principle cannot be applied in the case of knowledge by presence. Yazdi did not reject the truth criterion of concurrence—he showed that this is only applicable in the case of logical-discursive thinking and of knowledge by consensus on the basis of the partitioning into subject and object.

But when it is a case of knowledge by presence, one needs a different criterion. This criterion is given in the activity of the act of thinking. The activity of thinking creates a unified field in which the knower and the known appear as part of one and the same field. In this case, the object of knowledge is immanent and does not require any representation. One is, therefore, liberated from the necessity of showing correspondence. This does not mean that the knower and the known coincide. Yazdi speaks here of a correlation in the same field of existence.

The ‘I’ is Not a Thing

For Yazdi, the self-knowledge that arises during this process is a clear example of knowledge by presence. This is not (yet) the self-knowledge that can be developed in the course of a steadily increasing intensity of the capacity for knowledge, but it is a kind of prelude. Nor is it self-knowledge by psychology, which works with representations similar to mental pictures that only grasp the outer side. It is self-knowledge in the sense of becoming inwardly completely transparent to oneself as reality. In other words: Not knowledge regarding oneself, but rather becoming present in and towards oneself. Not a represented ‘I’ that remains a “thing,” but rather an ‘I’ that is revealed in presence. In the simplest case, when, for example, I say: “I know that my neighbor is at home,” there is a piece of knowledge (object of knowing) with which I naturally connect via the ‘I’ that knows this (the knowing one). Even if I leave out the “I know” and say solely, “My neighbor is at home,” I still connect the knowledge with the knower, namely with myself. There can be no knowledge if it cannot simultaneously be connected with someone who knows. When we look at a statement like “I know myself,” it is evident that I connect the “myself” as the object of knowledge with the “I” who knows.

The underlying motive for Yazdi’s argument was a subliminal contradiction with Russell and his analytic school. The reality of the ‘I’, whether it appears on the side of the knower or on the side of the object of knowledge, can only be known with knowledge by presence. If it is possible to know it as representation (knowledge by correspondence), it is reduced to an “it.” But then it loses all reality. It’s then a word that can be used arbitrarily in the play of language. In the case of the ‘I’, however, this nominalist game does not work. Yazdi wrote in his commentary on a passage in Suhrawardi that only the statement ‘I’ is radically different from all other statements and that the paradox of the subjective and the objective, that is: I or It, is abolished in this case.1 The ‘I’ that Yazdi means, in line with his great predecessors, is the ‘I’ that reveals itself in its perfect reality through the act of knowledge. The reality of my ‘I’ is experienced immediately—that is, without any mediation!—in the act of my thinking process. It should be pointed out that he used the logical reasoning of Suhrawardi to demonstrate this.

There are a thousand years between Suhrawardi and Bertrand Russell, but that does not mean that a comparison of their different paths to knowledge is not of current interest. Among all possible objects, there is one and only one that does not derive its existence from another object, and that is the ‘I’. The ‘I’ arises and exists from the self-observation that takes place in the act of knowledge. “This sort of ‘I’ can never be converted under any circumstances into ‘it’ or the like.”2 Yazdi spoke of an ‘I’ that has become unique and singular, in which every split has been overcome. Moreover, this ‘I’ is, as it were, the locus manifestationis (place of revelation) of the being of the human being and is this being itself. Thinkers, like Avicenna and Mullah Sadra, recognized this in the ayat an-nur, the verse of light from the Koran (Sura 24:35), in which the expression “nurun ‘ala nur,” “light upon light,” is used. For Yazdi this meant “presence.” A modern example of how knowledge and religion can intertwine with one another.

This article first appeared in Stil: Goetheanismus in Kunst und Wissenschaft [Style: Goetheanism in Art and Science] 45, no. 2 (St. John’s, 2023). Reprinted here with the kind permission of the editors.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

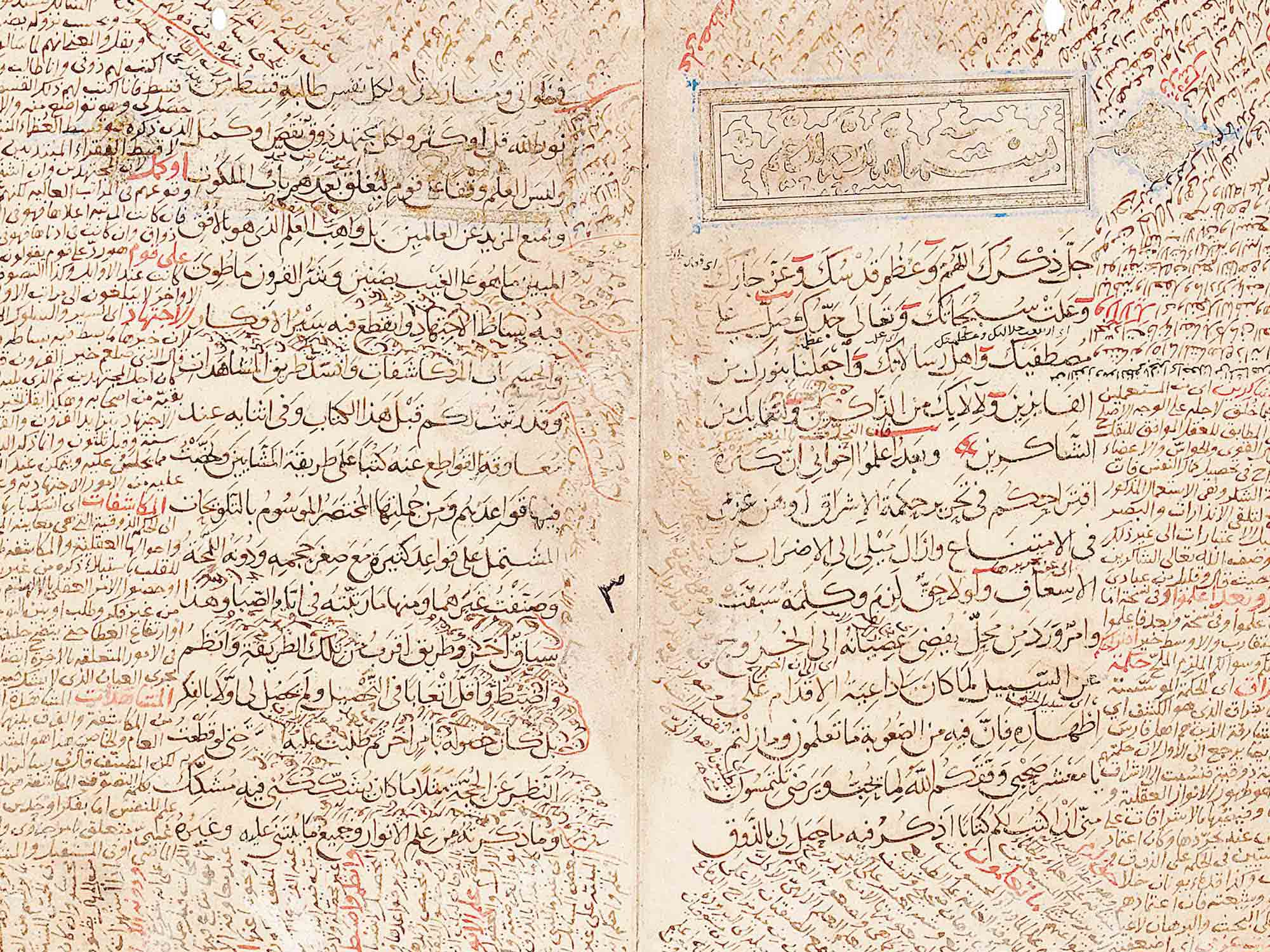

Title Image Shihab al-Din Abu al-Futuh Ahmad bin Habbash (Ya’ish) bin Amirak al-Suhrawardi al-Maqtuli, “Hikmat al-Ishraq” [Wisdom of Illumination] copied by Shams bin Jamal al-Hatani (post-Seljuq Iran), dated Tuesday, 14 Shaban AH 617 / October 13, 1220 AD. Arabic manuscript on paper.