A small group in Australia has taken practical steps to address an important question raised by many Waldorf teachers and Waldorf School graduates: what next?

Many a Waldorf teacher—including myself—has lamented the shortage of anthroposophically-inspired universities for their students to pass on to. Many a Waldorf student has felt a related wish. Indeed, the Year 12 students in the first Waldorf school in Stuttgart were so motivated that they made a formal petition for such a university to be created for them. Steiner recounted:

An appeal was signed by all the pupils of the 12th Class … ‘We should like to enter a university in which our education could be as natural and human as it is now in the Waldorf School.’1

Why, a hundred years after the signing of that petition, is there not a worldwide movement of Steiner tertiary education embracing a wide range of faculties, to match the worldwide and growing Waldorf school movement—something not just for Waldorf school graduates but for all young people seeking a “natural and human” form of university education?

The time is at hand. It is not difficult to recognise the sombre face of the crisis in our time. Events are taking place which give governments increasing control over citizens. It is a crisis of freedom. But crisis means a crossroads, a point of decision. Ours can be a time of firm decision and resolve to bring into existence the kind of university which is a worthy vehicle for the greatest aspirations of the human spirit.

This article presents a practical way forward, by summarising what a small group in Australia recently worked out in the form of a 100-page feasibility document, available to all who are interested (see below). Those endeavouring to create such universities don’t have to proceed in isolation: a network for mutual support could be created.

All knowledge, even purely scholarly knowledge, must merge into pure artistry.2

Rudolf Steiner

The Problem of Educational Freedom

Fundamental to Steiner’s views on the threefold social order is that cultural-spiritual activities like education should be entirely autonomous. Easier said than done. Steiner himself struggled with state requirements in setting up the first Waldorf school in Stuttgart. In most countries—including Australia—it is impossible: the government provides the building grants and controls the school curricula.

Government control of education is so ubiquitous that it might come as a surprise to learn that there have been places where educational institutions operate in freedom. For example, in 2003, when I was working in a Waldorf school in Switzerland, the school received no money from the government for building or anything else, and the government had no influence whatsoever on the curriculum. Students completed twelve years of Waldorf curriculum and then passed to a state school for a year or so in order to prepare for university. And, I must add, the school was full of students.

This autonomy, this freedom, is essential to the model of university described here. Its entire construction has the aim of ensuring this freedom. It was developed in the context of Australia, but it is likely to apply to any country.

In the proposed alternative university there will be a number of departments—including law and medicine—in which students are still going to need a qualification from a state-regulated university in order to enter the workforce. In these cases, the year or more spent at the proposed university will be additional and provide content that is deepened and extended through phenomenological insight. For others, however, the alternative university education will be sufficient to meet their needs. An entirely new form of degree will be offered, related to “the thinking of the whole human being.”

The Fundamental Structure

The fundamental structure of the proposed university is not a clever scheme to attract alternative or disgruntled students. It is not “worked out” at all. It is the expression of the archetypal threefold social form. One of the duties of the university is to be a beacon of the future. It will not be just a research and teaching institution, it will be an agent of social renewal through the very way it is organised and operated.

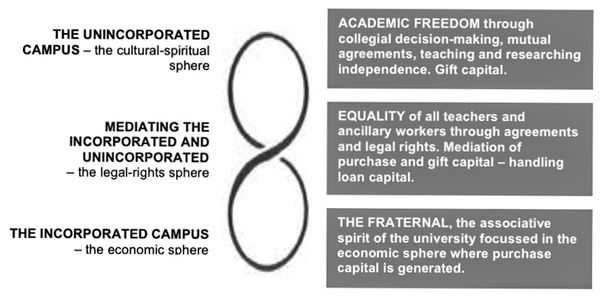

This university will be the threefold social order in practice: it will have a distinct and autonomous economic sphere working with the ideal of solidarity; it will have an autonomous legal-rights sphere working with the ideal of equality; and it will have an autonomous cultural sphere—which will be called “the faculty”—inspired by the ideal of freedom. What is crucial is the way this threefold structure can be made productive and viable, now and into the future—whatever obstacles it may encounter.

The Unincorporated Campus: The Cultural-Spiritual Sphere

The university faculty will constitute what we call the “unincorporated campus”: this is the teaching body of lecturers and tutors. It will not be any form of legal entity. In Australia, the government controls higher education, regulating the courses available and even the right to use the word “university”. It asserts this control inasmuch as a university is some form of constitutional corporation—in other words, a money-making entity.

The relationship between the members of the teaching body will take the form of an agreement that they will work out together, and it will be legally enforceable. The faculty will be made up of free individuals who do not receive payment as compensation for their work. This is in recognition of the fact that cultural-spiritual work like teaching is not an economic service. Teachers will receive money in the form of gift capital from the incorporated sphere, from students, and from other non-governmental sources.

The Incorporated Campus: The Economic Sphere

In the model we developed, the incorporated campus will be a biodynamic farm with which commercial studios, a bakery, or other businesses could be associated, according to the needs of the location and those who are drawn to the initiative. In the establishment of the campus, each of these businesses will be invited to become part of the campus on the basis that a certain percentage of the purchase capital generated is passed to the unincorporated campus via the legal-rights sphere, which manages a charitable foundation.

The teaching buildings will be on the same land as the farm, along with student and teacher accommodation and other facilities. The farm will also be important because agriculture will be one of the departments; all students will have the opportunity to work on the farm as part of their contribution to educational expenses. However, the entire campus does not have to be rural—there is no reason why some departments couldn’t be located in an urban environment.

As with the unincorporated campus, a legal agreement will form the binding factor—there will be no overarching corporate structure. The incorporated campus could be made up of numerous businesses that work on an associative economic basis which extends far beyond the campus, to distributors and customers.

Mediating the Incorporated and Unincorporated Campuses: The Legal-Rights Sphere

This dimension of the university will be made up of lawyers and administrators who deal with everything that binds the two other spheres of the campus into a healthy operating whole. Purchase capital from the incorporated campus and contracted contributions from students will flow into the charitable foundation. This foundation will be the conduit that transforms purchase capital into loan capital (passed to students as necessary) and gift capital to provide for the faculty and to allow for the construction of facilities.

This mediating sphere will support a “representative council” which will meet when necessary to work out issues affecting all three spheres. The mediating legal sphere will also handle matters of conflict resolution and any necessary legal action.

The Phenomenological University

The aim of this university will not be to teach anthroposophical spiritual science in the traditional “vessel waiting to be filled” approach. Rather, the intention will be to help students to see for themselves. In every aspect and dimension of teaching and research, students will be learning to enter the phenomenological pathway of knowing.

The phenomenological approach is what Steiner recommended, late in his life, in the so-called “college course” which was concerned with re-imagining academic studies. We “simply submerge ourselves in the phenomena”, as Steiner puts it. “Reading is the goal of looking at phenomena” is his indication.3 The appearance conceals the innate idea (eidos) which may nevertheless come to presence through the pathway of phenomenology: through phenomenological insight, “more appears than appears to appear”.4

The phenomenological approach will apply to all the departments. The ones presented in our feasibility document are agriculture, anthroposophical medicine and therapies, performing arts, architecture, law and politics, fine arts and creative writing, social science and social art, economics and business administration, education for people with special needs, and early childhood education.

At the heart of the university will be a Goethean science orientation course that will be undertaken by all students, in all departments, for all years of study. In the orientation study, the essentials of phenomenological research will be entered into, to then be developed to a far higher degree in each of the departments and through post-graduate research.

If you would like to be sent a copy of the 100-page feasibility document, please write to: ateliersocialquest@outlook.com.

Title image Symbolic, Photo: Xue Li

Footnotes

- R. Steiner, Human Values in Education, GA 310, Lecture 10.

- R. Steiner, Youth and the Etheric Heart, SteinerBooks, Great Barrington, CW 217a, 2007, p.15.

- R. Steiner, Reimagining Academic Studies, SteinerBooks, Great Barrington, 2015, GA 81, pp.13-15.

- R. Bernasconi, “The Good and the Beautiful” in Phenomenology in Practice and Theory, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Dordrecht, 1985, pp.179-184.

What a wonderful initiative. It gladdens my heart to hear of it.let us hope that the initiative takes root in the hearts of those who are capable of developing such a worthy enterprise.