What is the significance of tears today? Does what brings us to cry, bring us to our ‘I’? How do tears help us to find ourselves? A brief phenomenology of the spirituality of crying.

When the Pope died on Easter Monday, all the faithful in Rome wept. Outsiders may find this strange. He didn’t suffer a tragic death, like that of a child. For those critical of the Church, these tears were merely an expression of religious sentimentality. But when we cry, there’s usually more to it than that. Perhaps not in this case, where the individual experience and the suddenness with which we’re often struck by tears may have been suppressed by the collective emotion felt for the larger institution. For those sharing the ritual of mourning, it was the loss of the father, God’s representative, that was felt.

Rudolf Steiner occasionally spoke about the anthropological dimensions of crying and laughing, noting that they’re expressions of the ‘I’. There’s truth in crying (certainly more than turning to alcohol)—not “the” Truth, not only one truth, but something truthful. Crying can bring us peace and calm, after the tears subside. However, we can also become restless in a sense because crying is not something we do to shut ourselves off from the world, in order to then have “our separate peace.” When we cry, we’re actually revealing our inner selves to the world. We open ourselves in our need, seeking comfort; we reveal the fact that even to ourselves, our being/non-being is a mystery. And when we cry alone, just for ourselves, we reveal ourselves to the spiritual world, perhaps to the angels, to the deceased, and most certainly to Christ.

When we cry, we’re touched by our destiny. Words often fail us in our attempt to convey what can only be experienced in our own flesh and bones, and in our own souls. Tears reveal that we suffer in our destiny and the extent of our suffering. We may even cry out of anger that we can’t cry.

Whether genuine or not, all crying reveals its true nature. It doesn’t guarantee we will receive empathy in response. We’re not moved by the wailing itself, or automatically responsive to loud sobbing laments in which there’s always some loss of dignity and composure. Actually, it’s often more the quiet crying, the kind that asks nothing, that moves us most. Crying can even be intrusive; it can be faked; it can be used for emotional blackmail. It’s a bit embarrassing when soccer players, for example, change teams for more money and then shed bitter tears of farewell in front of the cameras.

We’re even touched by our own tears. We can cry out of gratitude, out of relief, or simply because we’re overwhelmed by life. We can cry as we marvel at the beauty of nature or a work of art. Tears may suddenly strike us during meditation, if, for instance, we experience something unexpected. Sometimes crying itself comes as a realization.

Lifting the Veil

What happens in the soul when we cry? A door opens; a veil lifts away. There may also be an effect on the person we’re with, who notices our tears. They may feel a hesitation now in our argument; they pause, let it sink in, calm their anger. Phenomenologically, crying sets something in motion. Hardened emotions dissolve, though there may not yet be a solution to the social or soul problem that gave rise to them.

Should we sometimes try to bring ourselves to tears? Would it help us to be more conscious of ourselves or of society? Not that we should start some kind of habitual ritual. Crying is something intimate that connects with shame. The expression “shed a tear” doesn’t signify a change in consciousness. But if we’re attentive during encounters with another person, not necessarily when they’re being “emotional” but when they feel touched or hurt in their inner essence, when they reveal their individuality, then in the moment just before, when the other person is not actually crying yet but their eyes become moist, and they may “pull themselves together,” control themselves, and activate all their forces to keep themselves from crying—in this brief moment a space of love can open up if I perceive it on behalf of the other, if I open the space for the other person.

“The tears well up, the Earth has me back,” says Goethe in Faust [line 784]. It’s the Easter moment, when, in the last second, Faust renounces his intention to take his own life. Crying has something to do with our existence as “fallen,” earthly, culpable human beings, with the gift of conscience.

When a video went viral during the last Bundestag [German Parliament] election campaign showing CDU [Christian Democratic Union] chancellor candidate Armin Laschet laughing with his collaborators while visiting victims of a flood disaster, it was considered a prime example of a personal media disaster, and his chances went down the drain from that point on. It didn’t matter that Laschet’s laughter may have been just a brief, all-too-human emotion that had nothing to do with the reason for his visit. The public reaction was one of stunned indignation. Those who meant well felt sympathy for his faux pas, while his political opponents gloated. Isn’t there a counterpoint to this? Isn’t there deep joy in seeing someone rediscover their own connection to themselves?

In the Gospel account of the raising of the young man in Nain (Luke 7:11–17), where Jesus arrived “on his way,” the Greek word for Christ’s “mercy” can also be translated as “being inwardly moved.” Christ’s compassion gives him the force to heal and to bring the dead back to life. Being moved implies that at that moment at the city gate, on a threshold, Christ felt the divine being raised up within himself, being stirred, and that he actually “wept” or trembled, even if it wasn’t overtly noticeable.

When we perceive that someone is on the verge of crying, we acknowledge that we, as humanity, are on our way together. There’s no judgment. Being on our way can include the infallible Pope as well as the irreverent politician. New paths often actually begin with a “failure.” We feel the inner relationship with the other, a sudden awareness of our spiritual longing that, in the phenomenon of crying, gives an “exoteric-physiological” expression to an esoteric mystery: the infinite depth of each and every human ‘I.’

Translation Joshua Kelberman

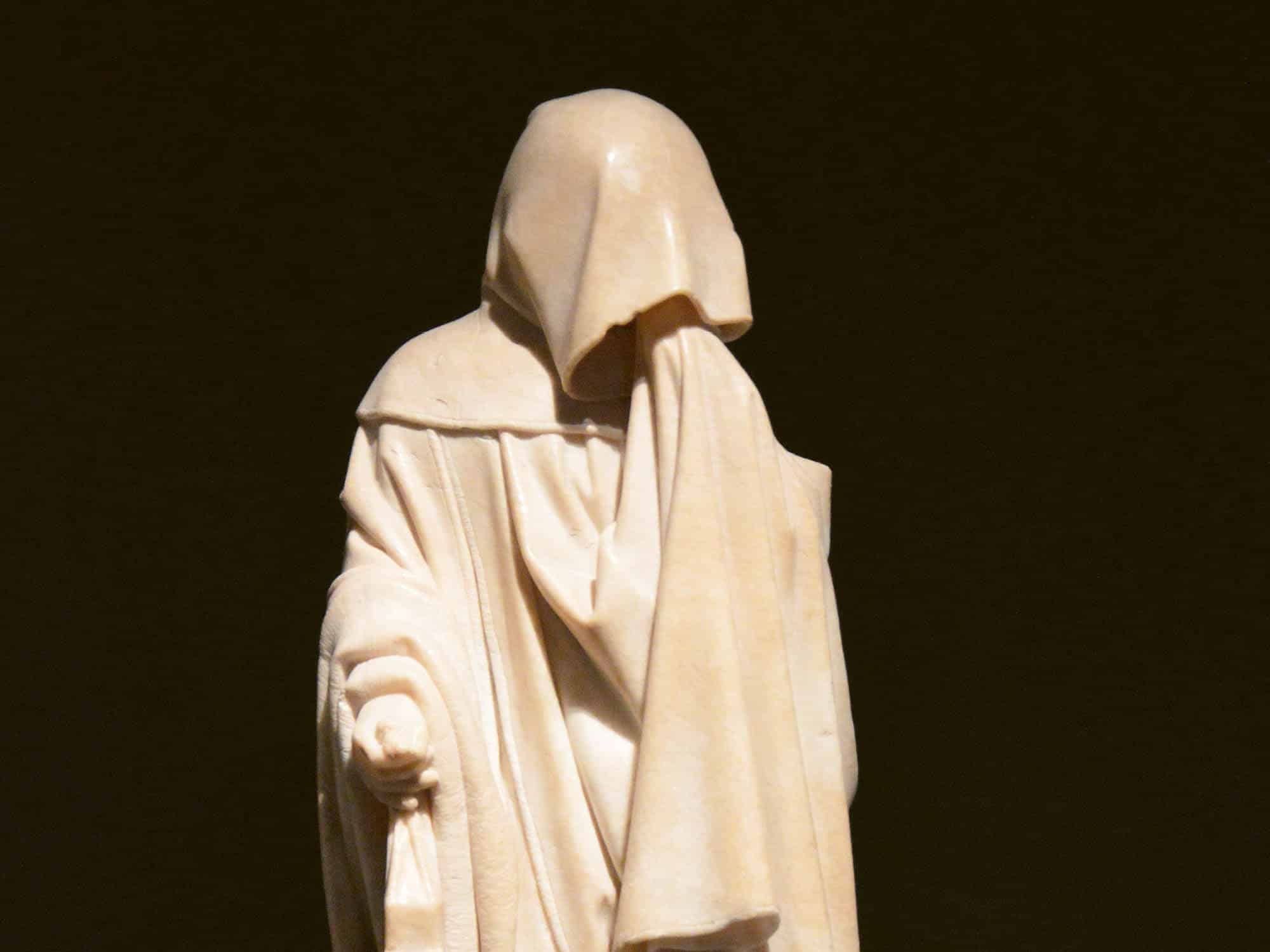

Image Mourners at the tomb of John the Fearless. Photo: Shonagon, 2013