How can we contribute to the search for the ‘I’ in dialogue and debates on cultural diversity, gender, identity, karma and reincarnation? This topic will be addressed in a forum entitled ‘Equal and Different!’ at the Goetheanum World Conference in September.

The several billion people who live on planet Earth are incredibly diverse. Everyone looks different and sees in a different way. Everyone feels and thinks differently, has different likes and dislikes, lives, speaks, and eats differently, prays and curses in their own way, turns or does not turn their thoughts and feelings to gods, calls them by different names, or does not want to call them by any, wants to devote themselves to one god or many gods; everyone also wants to call themselves differently as a person, as a woman, a man, or again, differently, many starve, others are opera singers or cowherds at the foot of Kilimanjaro, and still others cannot develop any creativity in their professional life.

These beings, so very different from each other, still call themselves and recognize each other as human beings. They feel that despite their differences, something common lives within them, something that connects them—something invisible, we could also say, that belongs to all of us equally. The editors of the 1948 Declaration of Human Rights put it this way: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and are to treat one another in a spirit of fraternity.” 1 The ideals of freedom, equality, fraternity, the possibility of developing cognition and morality—these lie as potential in every human being and establish their dignity.

Living in the Tension

There is a particular tension between the terms ‘equal’ and ‘different’ and a danger that we may focus our attention and efforts too much on one side or the other. Before the dawn of modern times, the ideal of sameness lived strongly in Europe—church and diverse orders cultivated a sense of commonality of religious and human ideals across geographical or linguistic boundaries. The split into Eastern and Western Churches in 1054 and the dissolution of the Order of the Knights Templar in 1307 are examples of it becoming less and less possible to feel the commonality in diversity. Sameness was enforceable—even if it meant using brutal measures—as forced uniformity. The way the Atlantic crossers dealt with the inhabitants of the Caribbean in 1492 belongs in this category.

Since the end of the 20th century, especially in the English-speaking world but also in Central and Northern Europe, there has been a strong ideal of observing and respecting diversity. Many people feel that it is a cultural advance if we perceive and appreciate ethnic, religious, cultural, linguistic, gender and other differences. But does a sense of invisible sameness or commonality among all people live in this awareness of diversity? More and more voices are raised, saying that talk of universal human rights and the ‘universal human’ was formulated by people of a certain group, and the claim that it applies to all people is just a tendency towards egalitarianism and this group’s claim to power.

On the scales of the conceptual pair ‘equal and different’, more weight is now placed on ‘different’. Whereas in the left-liberal milieu more thought is given to gender and cultural diversity, in the right-wing populist milieu more emphasis is placed on national and ethnic demarcation.

What Can We Learn from This?

What and how can those who are in search of the self—who assume that the human being has a reality beyond its spatiotemporal appearance—contribute to the debate about cultural diversity, gender and reincarnation? What do people who study anthroposophy and are inspired by anthroposophy in their professional and life practices have to say about these topics? And with whom do they talk about it—only with people who also know anthroposophy?

Rudolf Steiner puts weights on both scales, which becomes clear even in superficial study. On the side of ‘different’, for example: ” It is not how all people would act that must be decisive for me, but what is to be done for me in the individual case.” 2 Or: today, “more and more tolerance must prevail with regard to the thinking of religious life in particular.” “Because people are becoming more and more individual and individualistic,” it is important today that everyone “develop their own free religious thought life individually within themselves.” 3

And for the other scale, ” People are becoming more and more different in terms of the external, and this will have the precise effect that people will have to apply all the more strength from within, in order to come to unity.” 4 That the human being (every human being!) can develop this “strength from within” is possible because in the “unconscious or subconscious all already carry the Christ within themselves.” 5 Of course, this is not a politically correct statement from today’s perspective and understandably cannot be accepted by many. Can this “power from within” be described in other words without using this name? And what is the contribution of the idea of reincarnation and karma to the topic of equality and diversity, to the topic of human dignity and cultural diversity?

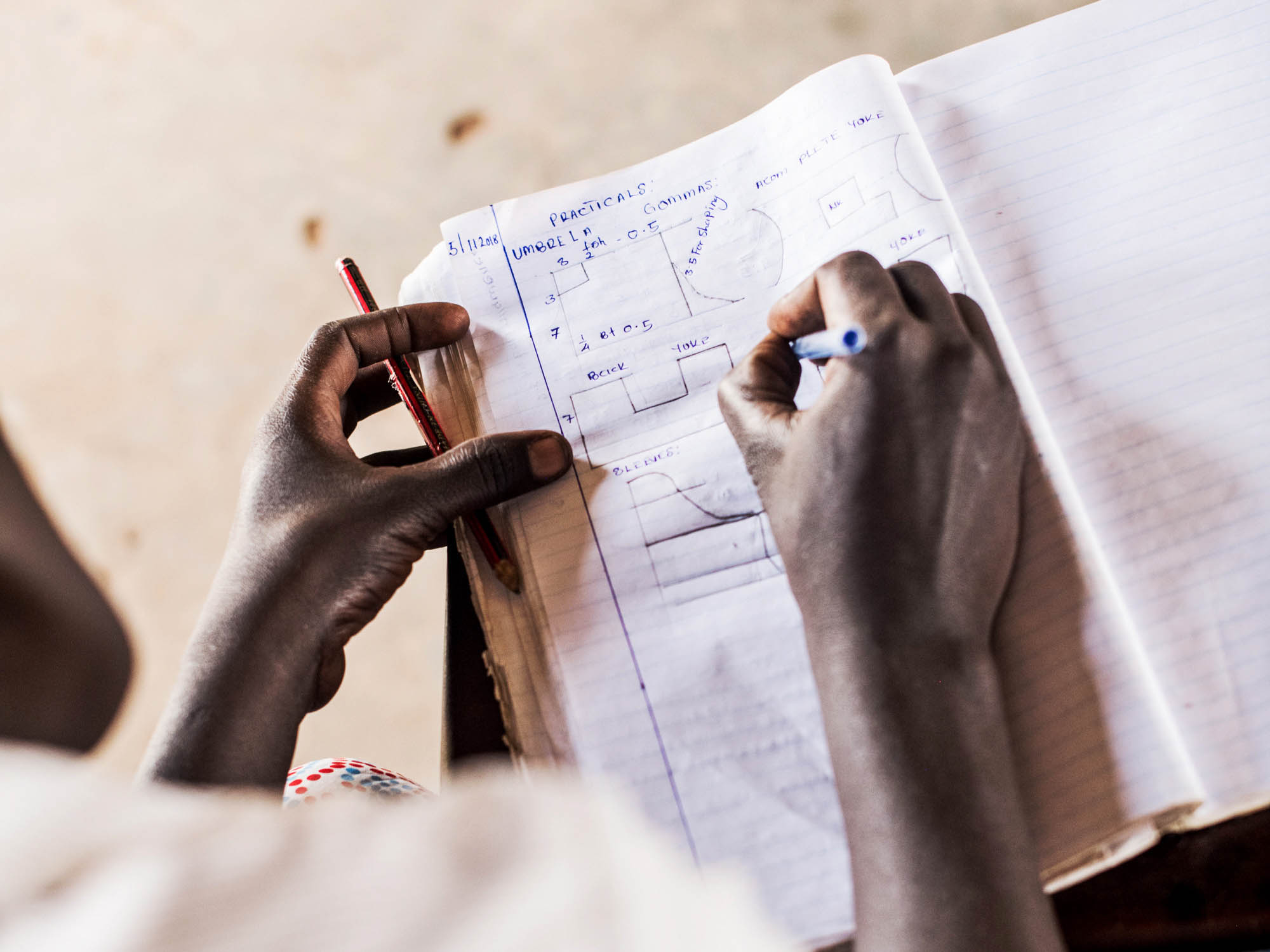

Practical Life

Many concrete questions arise from this subject area. For example, what about the diversity and identity of Waldorf and Rudolf Steiner schools, kindergartens, curative education and social therapy institutions in terms of methods, content and the relationship of the staff to anthroposophy? How is human dignity and the universally human promoted in the context of diversity of social therapeutic institutions? Through which methods and contents are gender stereotypes avoided? What is the contribution of anthroposophical pedagogy and curative education to an education that respects gender differences, keeping in mind the universally human?

Translation Charles Cross

Photo Alyssasieb via nappy.co

Footnotes

- Allgemeine Erklärung der Menschenrechte.

- Rudolf Steiner, Die Philosophie der Freiheit. GA 4, p. 159.

- Rudolf Steiner, Die Verbindung zwischen Lebenden und Toten. GA 168, p. 118.

- Rudolf Steiner, Die geistige Vereinigung der Menschheit durch den Christus Impuls. GA 165, p. 179.

- GA 168, p. 118.