‹The Heart Around Us› – this is the title of the upcoming annual conference of the Medical Section from 13 to 18 September. It is aimed at those working in the medical professions, as well as those with a general interest. It is about the therapeutic community. Wolfgang Held in conversation with Georg Soldner, co-leader of the Medical Section.

What does ‹a therapeutic community› mean?

Anthroposophic Medicine by its conception is what we call a multiprofessional system of medicine. Doctors, psychotherapists, art therapists, and above all nurses work together. Even a newborn baby needs a midwife, a gynecologist, and a pediatrician. Of course, this is not only true in Anthroposophic Medicine, but increasingly in modern medicine. Such professional team-building presents us with challenges. Yet people are trained separately in the different professions and have little or no training together before they then encounter each other in their professional work.

It takes a whole village to raise a child, so goes an African proverb. So this is also true in medicine?

This is also true in medicine! One example from our annual conference is the workshop on the Heart School with Jakob Gruber, a cardiologist from Herdecke. Many patients suffer from chronic heart disease after a heart attack. It has been shown that they can be given better help if patient groups are formed. In the best case, this happens in a therapeutic team, e.g. with a doctor, a biography counselor, a therapist, and a nutrition specialist. Interestingly, patients are more able to change habits and understand themselves in a community. This is more successful than working with them individually. A pioneer here is Dean Ornish in the USA, who already began working in this way as a medical student. This is very much in line with Anthroposophic Medicine.

So it’s not just about bringing together many different therapeutic professions, but also several patients?

Working with patient groups is playing an increasing role in chronic diseases, e.g. children with asthma. This has been common practice in psychiatry for a long time. In training courses, we find that a therapeutic community, including the community of therapists and patients, can release forces that go beyond what we experience in the individual. Especially with today’s chronic diseases, where nutrition and exercise play a central role and it is a matter of changing habits, this form of treatment has an increasing role to play. But every hospital is indeed also a therapeutic community.

Why does this work better in community?

Because then I see with other patients that they also have problems with their habits. That makes it easier to access my will. Anyone who is ill drops out of the community to a certain extent – out of a successful professional career, for example. A heart attack can tear me out of what gives me self-confidence and affirmation. Now it is an important experience that I am not alone in this and that many others feel the same way and that all of them are now also faced with the challenge of changing their habits. Perhaps in the course of such therapies, we also come into contact with people who have already succeeded in transforming their lives. It is about the experience of not being alone and also motivating each other. We know this from Alcoholics Anonymous. In the case of addiction, a strong force issues from the community.

You mention loneliness. It reminds me of these words from Rainer Maria Rilke, according to which loneliness is a basic feature of our society today. Would you also see it that way?

That is most certainly the case. The development of consciousness towards what in Anthroposophy we call the Consciousness Soul means liberation and this includes on its shadow side increasing isolation. If I used to be part of an extended family that regulated and commented on everything and determined the paths of the individual by social pressure, the development in modern society towards distance from others, which grew once again with the pandemic, offers the possibility to form a consciousness in reflection not just of others but also of ourselves. This leads me to face myself, to face myself like a stranger, as Rudolf Steiner puts it. In this, I am alone with myself. Loneliness is thus a characteristic trait of modern societies. On the other hand, many people are on this path, either through insight, through training, or through illness and destiny. At this level, a new form of community building becomes possible.

And community relates to the heart – or, why is the heart in the title of the annual conference?

For modern western societies with their materialistic view of the human being, the brain is the central organ of the human being, which in turn is now seen as a computer. However, the organ with which we experience, perceive, feel relationship and through which ultimately our conscience also speaks is the heart. Whether we behave empathically or hurtfully towards another person is not felt by the brain but by the heart. You can ask people all over the world to point to where they feel their core, their personality: they will not point to their head, but to their heart. The human I lives in the heart in a way that is capable of connecting with the world, of resonating with the other. The brain, in turn, is a mirror apparatus that enables us to form consciousness. The aforementioned loneliness is connected with this formation of consciousness. However, we can mirror ourselves there, but also the other. Only when we succeed in bringing together these qualities of brain and heart and hand do we find a complete relationship with the world, a relationship with the world that enables us to connect warmly with other people and to get out of this loneliness.

How is it possible for a heart to beat so faithfully all the time?

This incessant work of the heart is a unique function In our organism. We can by no means say that of the brain, or of the liver, that they function day and night in a certain way, as is true of the heart. The secret is rhythm, that which can be inexhaustibly active and absorbing. The heart fills, the heart perceives what flows into it and then gives it back to the surroundings. It perceives this very subtly and gains the strength for its own activity from it. Much of the energy that takes effect in the heart is actually fed in from the periphery and then transformed, transformed to a higher level. The heart draws from the periphery and at the same time, it makes everything new. This is how we can characterise this pulsating action of the heart. In breath and heartbeat unfolds what we have just talked about: the soul’s connection with the world.

The conference is also about when communities fall ill?

We have of course working groups on many medical and practice topics, for example on heart diseases. But we also look at the therapeutic community itself: every practice, every therapeutic centre, every hospital is an association of people who want to help people who are ill, and that is also a challenging activity. Take a hospice or a maternity clinic with 24-hour on-call, with unforeseen emergencies! In such a human community, conflicts inevitably ignite. My colleague Philipp Busche recently said that there are three great teachers: illness, social conflict, and error. There is no doubt that social conflicts are not uncommon in therapeutic communities. But today it is a matter of learning to resolve these conflicts at the level of the consciousness soul, at a modern level where the freedom of each individual is maintained. Indeed, the personal commitment of all staff should be able to increase. We should be empathetic with each other, empathetic not only with patients but also with colleagues and with ourselves. The challenge is that, especially as a doctor, I have to forget myself in an emergency and be completely centred on the patient. But I also have to come back to myself, to my surroundings, my own family, and my colleagues. That is important in the long run so that we can help patients sustainably as a community. In psychiatry, where this is particularly challenging, this has already been professionalised. But it applies to the whole of medicine.

Last week, the Congress for Inclusion took place in Zurich. I had a workshop there. One participant had an autistic disability and was dependent on augmentative and alternative communication. The group was asked what help everyone needed. Surprisingly, he said that it would help him if people were grateful to each other. He didn’t want anything for himself, but a climate of gratitude. What does that tell you as a doctor?

We can learn a lot from a person with an autism spectrum disorder and in doing so try to communicate with each other on an equal footing. I can only say from my own practice community: patients perceive the quality of the cooperation when they come through the door. And I also know of studies that prove that the atmosphere in the therapeutic community is just as important for the therapeutic results as the individual performance of the doctor or the therapeutic professionals.

In relation to atmosphere, you also explore the boundary questions at the conference, such as the question of community building with machines. What is the issue for you there?

If we look at a country like Japan, where we have a culture that is particularly marked by modesty, there is a tendency, for example, to replace personal hygiene and similar activities in care with machines, so that patients no longer encounter another human being. We need a clear, heightened awareness here. What is the difference? If we consider the human being as a soul-spiritual being, then they encounter nothing in the machine on this level. I am pleased that Jan Vagedes, who heads the pediatric department at the Filderklinik, and Rolf Heine, who is an expert in nursing, will be talking about this topic.

You will occupy yourselves with the question of how to include the deceased in the community. How can that work?

The reality of the deceased is also a central experience in my life, which brought me to Anthroposophy in the first place. The presence of the deceased – that has found its way into literature: there are some novels I have now read that have been published in recent years and that deal with this threshold question, such as ‹The Eighth Life› by the Georgian writer Nino Haratischvili, where the dead make an appearance, or also the book ‹The Forty Rules of Love› by Elif Shafak, a leading Turkish writer. The perception and presence of the dead in our reality is a recurring theme. These are best-selling novels. Many people have had experiences here, especially in Anthroposophical life. We want to talk about how we can take the presence of the dead seriously. I can say that in Anthroposophy we endeavour to speak a language that the living and the dead can understand. A language that the living and the dead can understand is a language that speaks of the essence and does not lose itself in that which has no meaning in the spiritual world, for the deceased. In this respect, community with the dead is a constant reminder of what matters.

Triggered by the handling of the coronavirus pandemic, a public campaign against Anthroposophy unfolded in the spring. The annual conference is intended to help defend against this. What does that mean?

Well, in recent years a strong negative public mood towards Anthroposophy has developed in some countries. It is part of the dynamics of pandemics that people look for someone to blame. Especially in Germany, with the experience of two world wars, this reflex sits in the subconscious. It is a phenomenon where you don’t have to look far in your personal life. You don’t want to be the guilty party, so you point the finger at others. In such a situation it is important to reflect on what is fundamental and to ask what the essentials actually are. At our annual conference, we expect people from 50 countries. We expect a large community and that gives us strength. We want to reinforce this strength and thus return to inner self-confidence and self-assurance.

You have given the conference a motto from a text by Wolfgang Schad. He writes about the peripheral I and replaces the ‹we› with the ‹I of humanity›. What distinguishes the I of humanity from the we?

I would like to call to mind here the second verse of Rudolf Steiner’s Foundation Stone Meditation. It refers to what is at work in the soul and how we connect with the cosmic I, and that in Christ death becomes new life. Then it refers to an I that is a future I, a true I, for each and every one of us. It is the Christ I, by which nothing denominational is meant. If we want to comprehend ourselves in the social sphere, where we take hold of our destiny and also help in the destiny of others and want to take responsibility for that – if we want to comprehend that, then we cannot only experience ourselves from the perspective of ourselves but we must also experience ourselves from the perspective of other. What the other person experiences in me, what they experiences in me, that is the morally decisive thing, that is what enters consciousness after death. That is what for me will be the impulse for a new, future life on earth. Where we place ourselves into the community in such a responsible, free and conscious way, we connect increasingly with what we can call the cosmic I, the great I of humanity. In doing so, our heart reflects how much we are connected with this great cosmic I.

Podcast The interview can also be listened to as a podcast at Die Wochenschrift für Anthroposophie und Spotify, Apple Podcast and others.

Event

‹The Heart Around Us. The importance and meaning of the therapeutic community›, 13 to 18 September 2022.

International annual conference of the Medical Section at the Goetheanum.

Information and registration

This article was translated by Christian von Arnim.

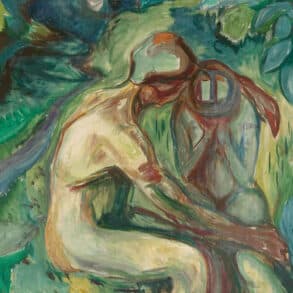

Pictures Miriam Wahl, Dshamilja, ten-part series, dispersion and watercolour on paper, 70 × 50 cm each, 2018