In Britain, Rudolf Steiner’s impulse is transforming the lives of children and young people with learning differences and difficulties. For the past four decades, Ruskin Mill Trust has used traditional crafts and biodynamic farming as tools for therapeutic education to support the development of human freedom. Now, a new book by founder Aonghus Gordon and Dr Laurence Cox presents the Trust’s method of Practical Skills Therapeutic Education as a vision of a better way of living for everyone.1

In 1981, Aonghus Gordon began working with local volunteers to renovate and reimagine a disused mill in the Cotswold village of Nailsworth as a centre for crafts and cultural renewal. In the now-renamed Ruskin Mill and the surrounding area, young people from a nearby Steiner special school came together with craftspeople to engage in a new curriculum focussed on skilled practical activities.

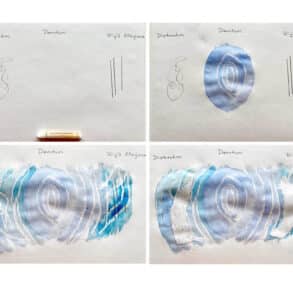

Traditional crafts, such as pottery, leatherwork, and working with wool (carding, spinning, felting, weaving etc.) complemented site-specific tasks such as rebuilding the huge mill-wheel. A café offered the chance to engage in service and called a biodynamic farm into being, one field at a time, where landwork skills could be developed. The lost potential of both the young people and the location were re-imagined together, in an approach deeply inspired by Steiner’s thoughts on education.

Today, Ruskin Mill Trust is one of Britain’s largest registered charitable independent Trusts providing special needs education for 16 to 25-year-olds. Its 15 provisions across England, Wales, and Scotland also include garden schools for children aged 6 to 16, RISE provisions for older people with lifelong care needs, and research centres devoted to Goethean enquiry and Rudolf Steiner’s spiritual science. In the process, it has also been able to offer a lifeline to many historic anthroposophical sites such as Sunfield (co-founded by Ita Wegman), Sheffield’s Merlin Theatre, Pishwanton in Scotland, Cherry Orchard Camphill and Bristol’s Helios Health Centre.

“Growing flowers or vegetables, cooking and baking, mending things and improving their houses, making music, tinkering with bikes or cars—these are not obscure or minority pleasures but rather things that people do far beyond what the simple calculus of time or money would suggest. We readily recognise and enjoy the skilled physical encounter with the material world outside ourselves.”

To now offer the Trust’s method of Practical Skills Therapeutic Education to the world, Aonghus Gordon and the Trust’s research consultant Prof. Laurence Cox, have written Place, Craft and Neurodiversity: Re-Imagining Potential through Education at Ruskin Mill, with a foreword by Dr Stefan Geider of Camphill.

Each chapter starts by bringing the reader on a walk around one of the Trust’s very different provisions—an old glass factory or metalworks, a garden school or a therapeutic community, or a research or training centre. As many readers will have discovered, simply telling someone about a project often leaves them cold, while showing them what it is like can often fire their imagination. Only then does the chapter seek to answer some of the questions that naturally arise in the visitor (or reader.) Following this, a conversation with Aonghus Gordon explores some of the spiritual underpinnings of the approach in a section that might be of interest to many readers of the Goetheanum Weekly.

The purpose of the book is to unpack some of what has been learned across four decades of consistent, committed work with young people facing, at times, very severe challenges, as something that can be of benefit to everyone for living a fuller, richer and freer human life.

“The good news from the student’s perspective is that if you don’t want to pick up the tool, you can’t do anything. And until you’re willing to pick up the tool, we actually can’t do anything for you… So by picking up the tool, the student has given you permission to work with their obstructed biography.”

Seven Fields of Practice

Ruskin Mill’s method of Practical Skills Therapeutic Education draws on Rudolf Steiner’s spiritual insights and contributions to pedagogy. It uses the work of John Ruskin, “the English Goethe” whose ideas inspired Tolstoy and Gandhi, and the practical visionary who revitalised craftwork for the modern world, William Morris, to explore what Steiner’s insights might mean in Britain. Over the years, the method has become expressed in seven fields of practice. These are key dimensions of our engagement with the world that are significant not only for young people on the autistic spectrum and with other learning differences, but equally for the staff working with them, and indeed, for anyone—as this book attempts to show.

The first field of practice is genius loci, the spirit of place: an appreciative, Goethean engagement with the geology, geography, plants and animals, human history, and spiritual qualities of each location whose potential the Trust seeks to re-imagine. The forms of craft and farming that are appropriate to the place, the histories that often weigh on the psyches of young people, and the land and the buildings where all of this takes place all need to be understood deeply and responded to appropriately.

The spirit of place then affords the possibility of developing particular practical skills in craft and landwork: some places have a history of engagement with wool, some with metal, or glass, or wood. These specific gifts of place enable the human being to encounter the resistance of the material world in locally meaningful ways: beating copper, carving wood, growing food, or tending sheep.

Young people whose communities were often called into being by particular industries that have since departed, and who themselves have been deeply failed by mainstream education, can develop their own skill (hand), cognitive understanding (head) and emotional maturity (heart) as they work with the realities of the world. In the process, they come to trust their own capacity to learn, they master the skills of each particular trade, and they create items of service that can be recognised by the wider community.

Thirdly, in the biodynamic ecology of the farm the young person—and the staff member who is working with them—can come to understand themselves in relationship to the farm organism, which allows them to encounter the weather, the seasons, and the stars; meet the rhythms of animals and plants; experience the interconnectedness of the different elements of the farm; and take part in a seed-to-table curriculum where they grow, harvest, prepare, and serve or eat food across the year.

Fourthly, all this enables a therapeutic education where the primary goal is no longer to train young people to become farmers or craftspeople—although some do go on to work in these fields—but rather to use this re-engagement with the material world and with one another as a form of practically grounded transformative education.

“When you realise that willows were grown extensively here, you can look, and ask ‘Has willow any relevance for today?’ …. Its value to the student, in having to arrange the chaos of 15 strands of willow to make the base of a basket, gives rise to a re-ordering of mental capacity, a mind clearance exercise.”

Fifthly, both in education and, for many of Ruskin Mill’s young people, in residential settings, holistic support and care are crucial. Drawing on Steiner’s seven life processes, a holistic view on the needs of students and pupils is maintained through seven care qualities: daily and yearly rhythms, physical and emotional warmth, good and appropriate nourishment, trust in themselves and others, a constant environment, a world of many kinds of cultures, and scope for recreation. This helps staff to provide warm and supportive environments within which children and students can develop and grow in their own ways.

Sixthly, both anthroposophic medicine and mainstream therapies are used to support young people’s health, together with the powerful tool of the student study, which brings together all staff members that are working with a young person to share their observations and ask Parsifal’s question: “What ails thee?”

Seventh and last, the field of (self-)leadership invites the young person, the staff member, and those holding other roles in the organisation to find the courage to do what the world needs of them in the service of others, enabling the development of self-generated conscious action as a way of being.

Each of the seven fields represents a dimension of engagement with the world: with the spirit of place, the skills of the hand, the ecology of the living world, the learning of each new generation, the care for one another, our physical bodies, and with self-leadership and leadership of others.

“[Blowing glass] takes courage, not just for the heat, but for the risk of getting it wrong in front of others, and care for those others while you move the molten glass on the end of its rod. You need to bring yourself to the point where you are willing to blow into a tube with hot glass at the other end or hold the molten glass with just a pad of wet newspaper as you shape it. This requires a lot of trust—particularly from young people whose pasts have often been deeply traumatic.”

Sharing the Learning

This method requires considerable thought and continued staff development, for which Ruskin Mill Trust provides extensive training and education for its over 1,200 staff members. This includes its own Master’s degree and sponsoring senior leaders to carry out PhDs in different academic disciplines that subject the method to rigorous examination. Underpinning all of this is a substantial research effort, including conventional, Goethean, and spiritual scientific research, supported by the Ruskin Mill Centre for Research (which includes the Field Centre in Gloucestershire, the Castelliz Centre in Wales, the Colquhoun Centre in Scotland and the George Adams Centre at Sunfield).

This research works through many collaborative connections: for example, Matthias Rang, co-leader for the Science Section at the Goetheanum, is a trustee of the Ruskin Mill Centre for Research and Prof Gert Biesta, Professor of Educational Theory and Pedagogy at the University of Edinburgh, is patron of the Ruskin Mill Centre for Practice.

Over the decades, Ruskin Mill has also shared the method in many practical ways: from courses and teacher training in China to the co-founding of Meristem College in California, collaborative farming projects with partners in Hungary, Czechia, and Italy, and in ecopreneurship networks spanning Norway, Iceland, and Britain.

Sharing the results of this research effort has always been an important goal of the Trust and is legally mandated by its charitable objectives. The Trust’s Field Centre website makes many of its publications, including the Field Centre Journal of Research and Practice and the In Dialogue journal, available free of charge.

Therefore, this new book has also been made available free as a PDF from Ruskin Mill Trust and in other ebook formats from Kindle, Kobo, etc. The print version can be purchased from bookshops around the world. It was launched at the AGM of the Anthroposophical Society in Great Britain on Sunday, May 12th, in Rudolf Steiner House, London.

“My view is that in the end, nobody can be left behind. I’ve never met a child or young person who can’t contribute to the world.”

More Ruskin Mill Trust

Footnotes

- Aonghus Gordon and Laurence Cox, Place, Craft and Neurodiversity: Re-Imagining Potential through Education at Ruskin Mill. London/New York: Routledge, 2024. All quotes and photos in the article above are taken from the book.