The feminine breaks down roles and points to the potential of possibility itself. Within the feminine, diversity becomes a creative force. The feminine delicately weaves through and around our differences. Where the feminine is welcomed, resonance arises—a new tone that connects rather than categorizes.

We are only at the beginning of the liberation of female qualities from being capacities only available to women. It’s not actually a matter of liberating the capacities themselves, but of liberating ourselves from outer limitations that inhibit these “female” qualities. The same applies to qualities attributed to men. Women and men still share a common religious, sociological, and cultural environment where they are both affected by various forms of outer control, even in the very use of language. “Female” and “male” are used as adjectives. When used as nouns, for example, “the female,” we remove them a little from this outer control and influence. Both the female and the male then become independent qualities of being that have their original source in what is universally human. The expression “the feminine” has its basis in what is female but is not identical with it. The “feminine” is a radically new quality in which both men and women participate. But this doesn’t mean that it takes on a double “role.” The “female” quality can neither be supplemented nor replaced by the “male” quality, and vice versa. A role always bears the trace of potential outer influence. One can even impose a role upon oneself. That, too, can be kind of outer control. However, what’s important is that the “female” and the “male” expand their self-imposed roles, that they develop a third quality based on being polarities. This opens up a new level. Here, independence stands at the beginning, and freedom is able to breathe.

For me, the “feminine” appears as this new beginning. It shines through the different qualities and gives them a certain brilliance. Similar to light that has passed through the darkness of outer subjugation and now, on a new level, bestows the brilliance of beauty as creative potential uniformly, on both of them. Bodo von Plato speaks of a new aesthetic arising from a relationship of polarities as a third quality.1 Today, emancipation from external control is emerging from the dichotomy that interprets sex and gender as the sole basis of a role.

A Little Background Information

In 1963, The Feminine Mystique by American writer and journalist Betty Friedan was published.2 With hindsight, we see how the book sparked a second wave of the feminist movement. By the 1950s and 1960s, women had become the object of deliberate mystification, with traits attributed to them and expected of them that they could not determine for themselves. The era of women’s initiative, which they had exercised for a short time during the war years, was over. Part of the mystification was that the role assigned to them as women was supposed to make them happy. The term “feminine,” now strictly bound to sex and gender, became a consumer good and was wonderfully marketable. However, the word “feminine” in the title of the book remained enigmatic. This gave rise to slogans such as “The future will be feminine.” An extremely important awareness campaign began.

What changes when qualities traditionally attributed to women by an external cultural and social context are now able to be developed independently, from within? It would be like exercising these existing qualities, but with the implicit intention to make what is already present shine with a touch of something new. This is the step from adjective to noun! This is the hour of the feminine. The feminine emerges as a new quality and resonates. It enhances the existing female and male qualities. Qualities become creative capabilities that work as a unified whole because they integrate the existing diversity.

In a subtle and nuanced conversation, three women [Joan Sleigh, Laura Liska, and Gilda Bartel] explored different qualities of the feminine.3 The primary aim of the feminine is to create a space wherein no one is excluded and to maintain this space, even if not everything accords with one’s own understanding. It is about paying attention to the inconspicuous, practicing a non-selective gaze, and understanding tenderness as a real force; it is a kind of sacred hospitality in which the door is opened even before one knows who is standing there. These qualities can also be seen in the masculine, as an expanded form of selfhood. A quality is elevated to the creative level of potentiality—pure capability that has no mandate, no purpose. The intention inherent in potentiality sets the creative process in motion and becomes effective. Where intention becomes effective, resonance arises.

One example of this is the capability to connect. Connection only takes place with something different (“the other” in nature, in the world, in fellow human beings, in oneself). There cannot be a connection between two things that are identical unless one merges into the other. The intention to connect is driven by the desire to connect, which can be set in motion without any external cause. It is a movement created out of nothing. Desire is all about the act of connecting—that is what my desire seeks. At this point, the feminine appears as that which can move on the creative level of possibility, of potentiality. It unfolds and becomes effective in the flow of becoming.

Shared Space of Experience

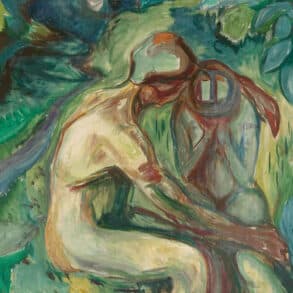

There is no capability predestined solely for women or solely for men. It wouldn’t then be a capability but rather an innate ability. Qualities can grow from an ability. However, abilities relate to each other in such a way that their mutual interaction opens up a space for experience. The “feminine” can dwell in this space for a moment. The medieval culture of minstrels and troubadours is an example. Starting in Occitania, they spread eastward and created a new world of images in a lyrical language in which words and sounds unite. They sang of the high art of love, of courtly love. The images found in the miniatures from the illumined Codex Manesse are still full of vitality. Man and woman meet in their mutual gaze in a blossoming garden. Between them, a delicate shrub weaves and grows, a young tree whose roots are taking hold. Its blossoms will soon bear fruit. Like a breath, the feminine envelops them both, their faces and figures. It sings of a moment lifted out of time.

Nowadays, the “feminine” is a quiet voice that weaves delicately and clearly through debates and antagonisms, yet it can still be heard. It becomes an art not to let the struggle for the feminine fall from its plane of creativity. It is important to keep the space of possible experience open as a dimension of what it is to be human. This space is not directly linked to sex and gender. Both women and men have equal access to this modality of possibility. Sex and gender, in their mutual exchange, form a fundamental polyphony. Sex—as given voice, as ground tone—and gender identity, which can be developed from this ground, are both necessary for this new dimension, these new “overtones,” to reveal themselves. Everyone, regardless of gender, can join in and use their own voice. At the same time, the feminine can detach itself from the ground tone and become audible as an unmistakable “tone of its own.” It reveals itself as an “expanding selfhood.” Ultimately, the feminine is a fruit whose seeds are not to be eaten but planted.

Adam’s Rib

I learned of the term “the feminine” from Emmanuel Levinas (1906–1995). He calls it “le féminin” as opposed to “woman” (la femme) and “femaleness” (la féminité). In one of his “Talmudic Readings,” he explains the passage in Genesis where God created woman from Adam’s rib. “God built into a woman the rib which he had taken from man” (Gen 2:22). Levinas gives the two main interpretations of Talmudic reading, from which all further commentaries and interpretations have developed over the centuries.4 In the first series of interpretations, the rib is an “appendage”; it comes after the creation of man. In the second series of interpretations, the rib can be understood as a visage, a face. After many twists and turns, Levinas suggests that God first created man as a single visage, in the image of God. God, as the radically other, has no face; he is the face. From this one face, God created two: concurrent and coequal.

Building on this, Levinas grants the “transcendence of otherness,” that which captivates me in the gaze of the other, its rightful place in his last philosophical writings. Emmanuel Levinas portrayed the face of every human being as a place of epiphany of the truly human. But not in such a way that I encounter the other in the face of my fellow human being as a “human being like me.” Levinas believes that only otherness can come to meet me as a face. Ethics as responsibility for the face of the other, i.e., granting them their otherness—for example, in hospitality—is one of the gestures of the feminine in Levinas. This creates an openness on the level of possibility as a dimension of the human. The feminine lets otherness in; it opens up the possibility for it to reveal itself as a face without having to or wanting to reveal itself.

The Feminine Touches Us

In the summer of 1981, my family spent a vacation in the area around the old Occitan bishopric town of Albi, France. A seminar on the topic of “Sacred texts and how they can (not) be ‘read’” was taking place nearby. I’d already decided to spend the day with our four little girls and was looking forward to our time together. Their father took part in the discussions. However, on the day when Emmanuel Levinas invited us to join the discussion using a passage from the Bible as an example, I decided to go along after all.

The meeting took place in a private apartment, and, to my surprise, I was not the only woman there. When we entered, Levinas and his wife, Raïssa, were sitting next to each other at a very ordinary table, and we sat down with them. They radiated a warmth that one could almost touch. All kinds of humor, gentleness, and openness interwove. She was knitting; he was reading aloud and commenting. They hardly exchanged a glance. The excited mood of the greeting and the tension around the upcoming discussions that had been there at the beginning subsided. It became quiet. Introspection and silence set in. Gradually, the intensity of their presence became effective—both of them together. They had met in their early twenties in Kaunas, Lithuania, where they lived on the same floor with their families. Their presence here in Cathar country was anything but “impressive” or imposing. They appeared graceful, cheerful, and light. When I think back now, I can only say: we were blessed. Between them, there was a presence that lightened our hearts and took away a burden we didn’t even know had been weighing us down—until that moment when we were able to experience what it means to be at home. And to feel this tiny, trembling life within us that never dies. Something touched us. Back at our vacation home in the evening, the girls, the oldest ones leading the way, ran to their father. I went into the kitchen to see if there was still any bread left.

Touch is essentially reciprocal: those who touch and those who are touched are two sides of the same coin. Sometimes it’s like when two strings of a violin, both struck by a bow, produce a single voice. A delicate vibration, a resonance, a kind of humming buzz, begins. From these vibrations, a constantly expanding experience begins to emerge. But the longing remains. If it were satisfied, one would have felt only oneself.

Potentizing Eros

It’s precisely in the tension between two “others” that the feminine appears as an intensification of Eros. This appearance is not a synthesis of the two opposites, female/male, nor is it a third element that cancels the two out. The uniqueness of the “feminine” is revealed in the preservation and maintenance of otherness—both types of otherness and the tension between them. It’s all about being able to maintain this tension! From the qualities of the male and female, a third, the feminine, emerges on a higher level. In it, the two become accessible and thus participate in the potentizing. If the feminine is reduced to a single otherness, for example, only to the female, no potentizing can take place from the polyphony. The longing for contact does not lead to fulfillment if one wants to keep the creative level of the feminine open. Any attribution, any classification, would rob it of its ability to become creative.

This is not about an addition that complements “female” and “male.” The feminine cannot be practiced either, because then it would be a return to a role model that someone imposes upon themselves. It must arise out of the potential. That is why both, female and male, are fundamentally incomplete, because potential does not carry any determination within itself. So one cannot set out to practice the feminine. Even becoming human is only possible because it is incomplete. There is a “more” that elevates both and yet honors each in its inadequacy, its incompleteness. Only then does polyphony arise, the high art of creating space for the voice of otherness by singing oneself. This is the inner secret of the culture of courtly love, from which the Fedeli d’Amore around Dante and his circle later developed. Those who love and those who are loved should be able to alternate in the game of love so that a third party can blossom and bear fruit in the middle. Fulfillment would be like a seed that you eat instead of plant. One of the secrets of high courtly love is that fulfillment was already there before anything began. The possible is there first, and from its abundance we sing the song of a new beginning—again and again—always new.

But everything that touches you and me

Welds us as played strings sound one melody.

Where is the instrument whence the sounds flow?

And whose the master-hand that holds the bow?

O! Sweet song

—Rainer Maria Rilke5

Sign of Vulnerability

A young woman carries her small child in her arms as she walks toward us, watching her. Her feet hover above a floor made entirely of clouds, almost without touching them. Her gait shows lightness and speed. Her veil billows with every step. But her stride toward us is also a descent. Her gaze is fixed upon what is revealing itself step by step below. She is paving a way. But it’s not her way. It’s the way of the child she is carrying, seemingly without any effort. Soon, both will reach the bottom of the path. From wholeness, they come to heaviness. The path and the wound now become theirs as well. In the summer of 1955, Wassili Grossmann stood in front of the “Sistine Madonna,” Raphael’s altarpiece, taken by the Russians as war booty in 1945 and exhibited in the Pushkin Museum. As a war journalist, he’d “co-authored” the unspeakable suffering and abysmal nature of World War II in his reports. From the moment he looked at the Madonna, a never-ending revelation took place within him:

I saw a young mother holding a child in her arms. How can one describe the magic of a delicate, slender apple tree that has produced its first heavy, white-skinned apple . . . the motherhood and vulnerability of a girl who is still nearly a child herself?

Ten years after the end of the war, the abysmal nature of war reappears to him:

Why is there no fear on the mother’s face? Why did she not clasp her son’s body with such force that death could not open her fingers? Why does she not want to snatch her son away from fate?

Countless times she’s come to him in the turmoil of war, a mother with her child. Now she comes towards him from the altarpiece. He sees her as his contemporary: “She is part of our lives, our contemporary.” But it is her son who opens his heart. Grossman sees in him how

the human in man… confronts his fate. And how vulnerability connects and heals opposites so that the human in man is not lost, for there is nothing greater.6

This article is part of a series that explores qualities of the feminine to bring them into greater conscious awareness and to consider how they might help in addressing the needs of our current world situations.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

About the Artists

Karo Kollwitz studied Fine Arts at the Bauhaus University Weimar and the HGB Leipzig. She completed a Master of Fine Arts program in Helsinki, Finland, and Weimar as a scholarship holder of the Heinrich Böll Foundation. She has been a guest lecturer at the Bauhaus-Universität Weimar since 2009 and lives and works in Weimar.

Sigrid Schenk lives in Witten as a mother of four, painter, and fellow human being.

Footnotes

- Bodo von Plato and Louis Defèche, “Aesthetics as a Spiritual Path,” Goetheanum Weekly (September 2, 2025).

- Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1963).

- Joan Sleigh, Laura Liska, and Gilda Bartel, “Giving the Unknown a Home,” Goetheanum Weekly (May 15, 2025).

- Emmanuel Levinas, “And God Created Woman,” in Nine Talmudic Readings (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), first published in French as Du sacré au saint: Cinq nouvelles lectures talmudiques [From the sacred to the holy: Five new Talmudic readings] (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1977).

- Rainer Maria Rilke, “Love Song,” translated by Jessie Lemont, Poets.org, Academy of American Poets, accessed October 22, 2025; first published in German as “Liebes-Lied,” in Neue Gedichte (Leipzig: Insel-Verlag, 1907).

- Vassily Grossman, “The Sistine Madonna,” in Tiergarten: Erzählungen [Zoo: Stories] (Berlin: Aufbau Verlag, 2008); first published in Russian as “Сикстинская мадонна,” in Очерки и рассказы [Essays and stories] (Moscow: Sovetsky Pisatel, 1955).

I found this a touching article which tries to make sense of the big gender questions. It takes the author nearly to the end,bringing a wide variety of aspects and examples to paint a picture of their understanding of the feminine, before introducing the term “becoming human”. The sense I got while wending my way through the article and toward this moment was the question: are you speaking about being truly human? About the “Christ in me”? Trying to give it a more accessible and acceptable expression in our contemporary context? I would be interested to hear how you would define the difference between the feminine and the truly human as shown in the “Menschheitsrepraesentant”?