The time of grand feelings lies in our childhood and in the childhood of humanity. Just like in our personal biography, historical epochs are not past and gone but, rather, have built the foundations of the human soul. What will become of this “Once upon a time”? What can the feeling life from the Egyptian and Greek epochs teach us now, and with that basis, how do we develop into the future?

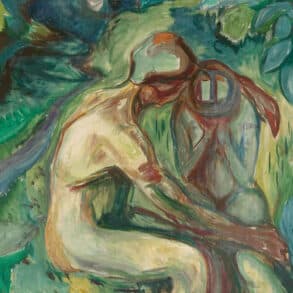

“Every human being is an Adam, for everyone is, at some time, expelled from the paradise of warm feelings.” 1 Goethe said this in his old age, and, indeed, if you seek grand feelings, you’ll soon end up in childhood, the biographical paradise. We are outside the world—our emotional life no longer has the impact that we remember it having from childhood. What was it like back then?

Let me give you an example: One day, in the 10th grade, our young teacher was being observed for her certification. The phalanx of examiners sat in the back of the classroom. Completely heedless, we carried on with our usual nonsense, until the principal’s voice boomed from behind us: “That’s enough! The children must learn a little something, at least. I’m taking over the lesson!” I don’t remember any other time in my life when I felt as guilty as I did in that moment—as the whole class did, together. Then, a note was passed around under the desks with the message: “Now, even worse!” I can hardly remember ever being that grateful again for such a saving grace. What courage drove us all on and brought the principal to utter failure. At the bell, the row of teachers left the class. Our teacher was the last to leave. Before she left, she turned around and looked at us for an eternity with an unmoving expression. Then, she dismissed us with a smile, a smile so slight that no camera would have captured it. But we saw it. And our hearts glowed.

“Children are giants; they’re just too small for camouflage.” Perhaps this line by singer-songwriter Reinhard Mey applies to our life of feeling. With every year, we grow up and become wiser and more skeptical; the grand feelings disappear, and a world of media “feeds” us feelings and emotions from speakers and screens. It may be worth going back for a moment, let’s say, four and a half thousand years ago, to the “childhood” of humanity, to the time of truly “grand feelings.”

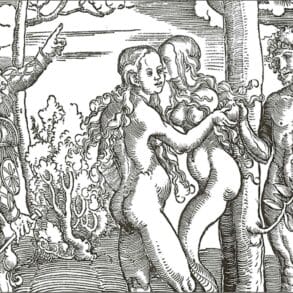

How did people feel in ancient Egypt? How did people feel in Greece and Rome? We live in a different world, not only with all our technology but also in our soul experiences. One of the strongest influences on our life of feelings today is only a few hundred years old: the idea of the “companionate marriage.” [Beginning in Elizabethan times,] it gradually replaced the marriage of convenience during the Romantic era.

Today, the feeling of numbness—depression—is considered the most prevalent soul disease of our time; poverty of feeling is a sign of the culture. It’s rather thought-provoking to consider that all religions originated in the desert, the wasteland. So, we can ask ourselves, “What does it mean to live in our current ‘emotional desert.’” I’ve visited the Atacama Desert, the Sahara, and the Gobi on various research trips, and the primary experience they all had in common was that the big became small, and the small became big. Before we explore what doors this key might unlock, let’s go back a bit further.

In the Childhood of Humanity

There is a song of lament from the time when the rule of the pharaoh, the unity of the country, broke down in Egypt—when chaos took the place of a golden age. What we hear reported from Syria today may have happened in a similar way, on a much larger scale, at that time in Egypt. The pharaoh organized the country and all circumstances of life in ancient Egypt. But, after 700 years or so, the officials in individual districts became overly independent. One great pyramid became many smaller pyramids. The country plunged into crisis. Legend tells us that a scribe, Ipuwer, expressed his feelings in a lament. It is a dive into the feeling life of the sentient soul:

Verily, every face goes white with fear, for archers are arrayed in order, evil is everywhere . . . . Verily, the women are barren, and none conceive, Khnum does not shape men because of the condition of the land. . . . Verily, the heart is horrified, for affliction pervades the land, blood is everywhere . . . . Verily, the people are like ibises, for filth pervades the land, and there are none at all in our time whose garments are white . . . . Verily, the land whirls like the movement of a potter’s wheel . . . Verily, the crocodiles belch from the fish they have seized . . . . Verily, the desert pervades the land . . . . Verily, rejoicing is perished . . . . Verily, deafness has set in with regard to complaints . . . . Verily, old and young say, ‘I would rather be dead,’ and even little children say, ‘No one should have given me life.’ . . . If only this were the end of men! No more conceiving! No more giving birth! Then the land would be hushed from its discord, and its turmoil would be no more.2

We can also take “The Great Hymn to the Aten” [the sun-disk deity] as a more positive example of grand feelings. “Whenever you are risen upon the eastern horizon you fill every land with your perfection. You are appealing, great, sparkling, high over every land.”3 The richness comes out here, too, though it’s more vivid in the despair of Ipuwer. Ipuwer’s feelings reflect what happens in the world directly, within the life of sensation. Resonance instead of detachment. Egypt: a life in feelings and sensations. Today, it is the cleverest technology and the most talented artists who help us enter into this Egyptian state of consciousness in order to encounter the world again. Enthusiasm and outrage are the poles of this more immediate life of feeling, where the soul responds directly to the outside world. Wherever outrage and enthusiasm run through the soul, we can say that we are in an Egyptian state of consciousness. This thought may help us not to be disappointed that it is so difficult today to bring the soul into a state of pure enthusiasm—a thought that also helps us question when indignation arises.

Culture and Control Over Emotions

As consciousness evolves, the life of feeling grows. In the land of Ancient Greece, with the birth of science and the arts, a time emerges in which it is no longer a matter of living in feelings. In Greece, the life of feeling was cultivated and ennobled. There is hardly a more magical place that still breathes this lifted-up life of feeling today than in Epidaurus. With its oracle, Delphi stood as the training ground for thought; Olympia trained body and will, but Epidaurus was a sanctuary for the healing and art of human feeling. At the entrance to the lovely plateau, the following was written above the temple: “Pure must be he who enters the fragrant temple; purity means to think nothing but holy thoughts.” 4 Henry Miller was able to capture the magic of Epidaurus, the temple of feeling, in the description of his trip to Greece, The Colossus of Maroussi:

The day began in sublime peace. It was . . . a hushed still world such as man will one day inherit when he ceases to indulge in murder and thievery. . . . Is the light too ethereal to be captured by the brush? . . . It is sheer perfection, as in Mozart’s music. . . . Defeating our neighbor doesn’t give peace any more than curing cancer brings health. Man doesn’t begin to live through triumphing over his enemy nor does he begin to acquire health through endless cures. The joy of life comes through peace, which is not static but dynamic. No man can really say that he knows what joy is until he has experienced peace. . . . Our diseases are our attachments . . . . At Epidaurus . . . I heard the heart of the world beat. I know what the cure is: it is to give up, to relinquish, to surrender. . . . Epidaurus is merely a place symbol: the real place is in the heart, in every man’s heart, if he will but stop and search it.5

Be it in the human scale of the Greek temples or the Aristotelian ethics of the midpoint, Greece was always about cultivating and ennobling the life of feelings—not about living in the feelings that nature herself gives but rather about shaping and developing feelings. In ancient Rome, this is staged. Caesar returns from his campaign in Gaul. Thousands upon thousands of citizens line the streets, cheering and shouting. Certainly, the emphasis here is on grand emotions. But, amongst the din, a simple soldier stands behind Caesar on the chariot and whispers in his ear, “Memento Mori”—remember death, remember that you are mortal. Now, that is mastery of feeling! In Pompeii, a patrician villa was excavated, and a legionnaire was found buried in ashes, still keeping watch, holding his lance. Here, we get a glimpse of the stoic life of feeling with its potential to suppress all feeling to the point of dehumanization! That was also part of Rome.

Life in the Desert

And what about us, today? I once stood with a tour group at the foot of the Andes in the Atacama Desert. With the morning sun behind us, we gazed at the natural spectacle: the majestic three-mile-high peaks glowed red, while the foot of the mountains shimmered in an uncanny blue in the dust and haze. It was like fire floating on water. Gazing at this colorful phenomenon, someone muttered, “Well done!” and thereby expressed today’s alienation and indifference towards the world. Things and phenomena of the world hardly have a story anymore that tells of their richness and evokes our feelings. We no longer experience their aura. Where over-abundance surrounds us, where everywhere a dozen options perpetually present themselves, in this land seemingly flooded in possibility, “anything goes,” and, therefore, nothing does, and no one has any consciousness of value anymore.

“Depression,” the feeling of numbness, has become a way of life. It is the world of media that now provides the old, grand feelings. Whether the design of a new gadget or some interesting camera angle in a film, it is the atmosphere that counts. To provide today’s soul with excitement and emotion, cheerfulness and sadness every day, and thus to transport it for an hour or two into an ancient state of happiness, and thereby allow it to forget its dried-out soul life—that is the skill of today’s world of media.

When the Little One Grows Up

The emotional desert is not so different from the natural desert: the small becomes big, and the big becomes small. Those who make peace with the fact that the world no longer “serves” us with its feelings, that both outrage and enthusiasm are feelings of a bygone era, these peacemakers also learn what is able to grow in the desert and, in fact, only in the desert. Here, new feelings can unfold in the soul, but not natural or God-given feelings. They no longer arise reflexively but must be self-created. Jörgen Smit calls this “acquired idealism.”6

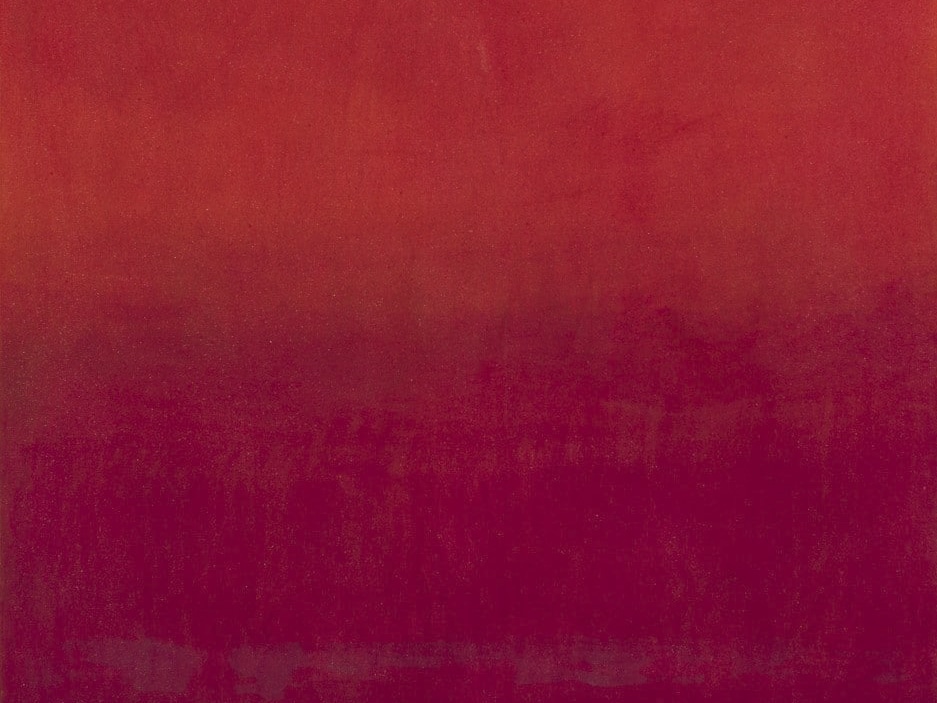

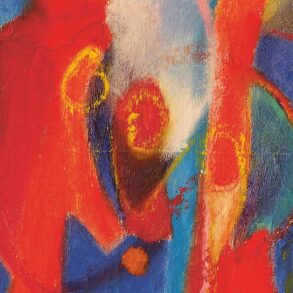

Contemporary art is the great schooling here because its works no longer evoke feelings, but wait for the viewer to bring feelings to the work of art. We’re helped here by switching from the old question: “What does the work want to say to me?” to a new one: “What do I want to say to this work? What, perhaps, might it want to hear from me?” Initially, we stand speechless before the hermetically sealed image. But then, subtly, a new feeling begins to grow out of the despair that confronts us from our lack of experience. This new feeling is quieter than the grand, classical feelings and, thus, can only be experienced upon a “nutrient-poor” soul soil. We’re not dealing here with a raging fire but with the resting coals, smoldering, covered in ashes and soot. While the old, natural feelings tended to classify an encounter and, through this identifying, close off their boundaries, these new, self-created feelings mark the beginning of an encounter, an opening. And like everything new, they are quite inconspicuous.

The artist and seminar director Alexander Schaumann gave us the key to this source of new feelings: we must forbid ourselves from saying, “I know that already.” Instead, a wealth of interest and unbiased empathy are the soil and fertilizer in which new feelings will be able to grow. These qualities liberate us from the indifference of being overly clever human beings.

What Ripens in the Silence

What is it like to no longer feel guilty that we don’t feel any devotion in the presence of the soft light of a candle, or if at the sight of a suffering animal or human being, we don’t feel true depths of compassion? What if we understand our emptiness of soul as an invitation for us to ensoul the moment ourselves through the reception and individuality of our ‘I’? The present moment, otherwise lost in the accelerating whirr of time, will then celebrate a resurrection as a moment of “created Now.” The more boring a conference, the more trivial a human encounter, the more superficial a lecture, the more these moments attract this possibility to generate a renewed inner life. We are not suggesting some kind of “super-charging” of the moment with soul. That would be tending toward a kind of (ahrimanic) insensitivity to the spirit of the other or (luciferic) a self-satisfying sentimentality. Instead, we are referring to the creation of resonant spaces within ourselves, where something hidden and concealed is given the possibility to reveal itself. “The human being is the soul of nature,” said Friedrich Hegel. Creating new feelings means comprehending this Hegelian sentence as a life mission. Instead of using up the Earth’s resources in today’s affluence, we can receive her life and give it the means to grow within our souls.

We should take Rudolf Steiner’s verse literally: “The stars once spoke to human beings. It is world-destiny that they are silent now.”7 The stars—but also the trees, animals, and fellow human beings—no longer “say” anything about themselves. Presumably, we could even say this is true of anthroposophy, that it doesn’t tell us anything about itself without our engagement. Joachim Daniel generalized this by saying that anthroposophical concepts have lost their aura. This fearful silence is perhaps necessary in order that we become capable of speaking. Steiner continues: “But in the deepening silence, there grows and ripens what the human being speaks to the stars.” Could it be that the feelings, dispositions, and atmosphere of moods that we, ourselves, produce, could it be that this is the herald of a new language of the stars?

Just like in a biography, historical epochs are not past and gone. They are like a layered painting; they are the ground underneath the present. That is why outrage and enthusiasm, as “Egyptian” feelings and a “Greek” mastery of ennobled feeling and passion, are not past but rather have built the foundations of the human soul. Still, let’s not forget that neither these grand feelings nor their mastery, will alone lead our further development into the future. Rather, new feelings, so imperceptibly inconspicuous, in their very beginnings, carry within themselves the seeds for the future.

More The article is based on Wolfgang Held’s presentation at the May 2015 Social Science Section conference, “Mensch und Organisation” [”Humans and Organization”]. Available as pdf at Wolfgangheld.de.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Eugen Korn, Goethes Gespräche [Goethe’s conversations] (Paderborn: Salzwasser, 2014), p. 73, conversation with Johann Ch. Lobe.

- William Kelly Simpson, ed., The Literature of Ancient Egypt, 3rd edn. (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2003). [The authorship and historical context of the Ipuwer text is much debated among Egyptologists—Trans. note.] Some historians date Ipuwer’s words of exhortation to the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt, c. 1600 BC.

- William Kelly Simpson, ed., The Literature of Ancient Egypt, 3rd edn. (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2003). [The authorship and historical context of the Ipuwer text is much debated among Egyptologists—Trans. note.] Some historians date Ipuwer’s words of exhortation to the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt, c. 1600 BC.

- Emma J. and Ludwig Edelstein, eds., Asclepius: Collection and Interpretation of the Testimonies, vol. 1 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1998), testimony 318, pp. 163–64.

- Henry Miller, The Colossus Of Maroussi (San Francisco: Colt, 1941).

- Jörgen Smit, Meditation: Transforming Our Lives for the Encounter with Christ (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2007).

- Rudolf Steiner, Verses and Meditations, translated by George and Mary Adams (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2004). Translation slightly revised.

Mein ‘willen’ lebt in meinen gliedern, wie meine gefuhle im blut zum herz leiten, das diese wunderbarheit meine Gedanken entzunden .. herzlichen danke Herr Held fur diese beweisung.