What happens when the concepts we have formed no longer apply? When we say ‹nature›, but nature is not addressed or does not understand itself to be addressed? The sociologist and philosopher Bruno Latour, who died in October 2022, in one of his last works, developed the thesis that we have not yet landed on earth. He proposes a new political force that could break open and unite the hardened opposition between populists and progressives. The work appeared in 2017 under the title ‹Où atterrir?› and was published in English under the title, ‹Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime›.

Following Bruno Latour’s thinking, we do not live in a world of objects but in one of forces. However, this does not correspond to the dominant scientific paradigm. He speaks of the need for a second revolution that transforms Galileo’s scientific revolution of an objective, scientifically describable, and controllable world into a way of thinking that recognises the earth as a living being. In the world of ‹Galilean objects›, the earth is seen as a laboratory. Through the insight into physical, chemical, and biological laws, things are stacked and built like a child builds their world with Lego bricks. This world of objects is the result of a view of the earth from the outside. Nature is viewed from the universe, from the distance of this great expanse out there, in the conviction that this makes objective comprehension possible. From this follows a concept of cognition that says: «To comprehend is to comprehend from the outside. Everything must be viewed from Sirius – a merely imaginary Sirius which no person has ever reached.» (p. 81)1 This view from outside, from a merely virtual position of apparent objectivity, had created confusion in the concept of nature.

In a somewhat too light-footed derivation, Latour points to the transformations of the Latin ‹natura› and the Greek ‹physis› in the early modern period. Natura, which could be translated as origin, production, process, and course of things, was replaced by a concept of nature that exclusively pursued a movement viewed from the outside. The new concept of nature maintains a connection between science and nature that completely loses sight of the inner side of nature (p. 82). The confusion, then, lies in the flawed concept of nature; or even more pointedly: it lies in the ideology of ‹nature›, i.e. not necessarily in science per se, but in a specific connection between science and nature: «What we need: to build on the entire power of the sciences, but without the ideology of ‹nature› that was linked to it. We need to be materialistic and rational, but to apply these qualities to the right terrain.» (p. 78)

The ‹New Materialism›

Latour’s concern is to dissolve the interlocking of nature and science that has come to be taken for granted in the way it has developed in the above sense since the early modern period. It is the view from a distance that prevents us from comprehending nature. This distant view is the ideological core he wants to break with by reversing the view to start instead with that which is very close by. His call to be «materialistic» can be understood as a turning towards the earth. He calls for us to engage directly with the earth in its concrete agency, without the abstraction of distance and without ideology according to the model of the falling body, the only permissible movement. This means that we disempower the mechanistic view of the world that placed all other movements — above all nature animated from within — under suspicion. (p. 83)

Bruno Latour belongs to the milieu of an interdisciplinary school of thought that has developed over the last 20 years. This heterogeneous current, summarised under the keyword ‹New Materialism›, represents not only the fundamental concern to overcome the central positioning of the human being (anthropocentrism), but also the conviction that matter is not passive, mute and unchangeable, but rather is to be understood as an active power. It is necessary to disconnect from two ideas: firstly, that only the human being stands as a thinking subject and actor in relation to a mute nature, and secondly, that we merely represent the world in our thinking, that is, we duplicate the perceived thing in the form of a weak image in our consciousness.

Both lead astray or, in Latour’s words, away from the earth. Karen Barad, a prominent proponent of New Materialism, substitutes a performative understanding for representation and passivity: «In contrast to representationalism, which situates us above or outside the world we supposedly only reflect upon, a performative approach emphasises thinking, observing and theorising as practices of engagement with and as part of the world in which we exist.»2

Karen Barad’s thrust is related to Latour’s, even if her explanation of why we are above or outside the world is based on a different critique. It questions the power of language, the fact that we take grammar too seriously and assume that its categories reflect the underlying structure of the world. Practices, activities, and actions become more important than reflection and the categorial classification of phenomena, relations more important than things: «Relationships do not depend on their relata, but the other way round.»3 For Latour, we have moved away from the earth because, in the course of modernity, we began to look at nature from the universe instead of looking at it from the earth, because we have driven out the nature that grasps from within all phenomena of genesis. (p. 83) Idealism sits deep within us and shapes our lives. We use a GPS to locate ourselves precisely, and because we are idealists, we do not realise that we are operating an instrument that determines everything from a distance and misses location. The GPS is precisely unable to determine location in Latour’s sense. The locator smooths out all inconsistencies and gives the appearance of a single, large entity.4 It lacks moisture and relationship — corporeality with all its contingencies and flaws.

We Have Never Been Modern

Latour echoes James Lovelock’s and Lynn Margulis’ «Gaia hypothesis» from the 1970s. It says that the earth is a living being of which we are an integral part. Planet Earth is not just one body among others, but completely unique. Instead of a collection of Galilean objects, the earth is a world of agents or actors with whom humans are in exchange. (89) Paradoxically, the Gaia hypothesis is said to have been inspired by the so-called «Overview Effect»5, a feeling of awe and connection with life on Earth that space travelers experience when they see planet Earth from space for the first time. Neil Armstrong coined the phrase «Blue Marble» when he was in space in 1968. For the first time, humanity saw the globe as a holistic, vulnerable, and fragile organism. However, this real view from afar should not be confused with the constructed view from Sirius described by Latour. It is one of the great moments of the last century. Humanity needed a moon landing to realise that the much more exciting thing is the earth itself – but landing on it is not so easy.

Latour’s critique of the concept of nature joins his repeated critique of modernity. ‹We Have Never Been Modern› is the title of one of his major works. The starting point for this book, however, is a political one, namely the election of Donald Trump on the 8th of November, 2016. With this presidential election, Latour connects three phenomena that began in the early 1990s but were expressed in a stark way during the latter time. Firstly, the so-called ‹deregulation› of the market; Secondly, an «ever more dizzying explosion of inequalities» that set in as a result; and thirdly, the systematic denial of climate change. Behind these three phenomena lies globalisation, with its dreamed-of freedom and openness to the foreign, with the dissolution of borders, with the increase in cultural diversity and unhindered exchange. The hope of the globalisers has been dashed – everything has turned into the opposite. What happened? Why do we feel so acutely today «that the ground has been pulled out from under our feet»? (p. 14)

Globalisation, which was supposed to mean that we broaden our attention, that we increase our points of view, that we consider a greater number of creatures, cultures, organisms, and people, has in fact not come true. Instead of the many views, a single view has prevailed over all others; a view that is «provincial by design, proposed by a small group of people, representing a tiny number of interests, limited to a few measurement tools, standards and forms» (p. 21). The expansiveness turned into an uncomfortable narrowness. It is not surprising that the ruthless simplification and the monotony-inducing globalisation have triggered a reactionary retreat to the local.

The slogan of the globalisers is ‹modernisation›. In contrast, the advocates of local traditions oppose this with the affiliation to a country, a people, a certain soil with specific ways of life and trades, with certain crafts and a cultural canon that must be cultivated and preserved. Like globalisation, the local also has a flip side, namely the fear of what is foreign and different. Politically, this comes to expression in ‹populism›. Populism seeks protection, tradition, identity, and certainty within national or ethnic borders; but it does not find them in the old local – because even the most remote stretch of country has now been swept up in the wave of modernisation. And because the local cannot be modernised, the local as restyled by the populists no longer bears any resemblance to the old one and it is no more habitable than the world of misguided globalisation. (p. 40) The world was either modern, but under its feet there was then no longer a world, or it was a real world, but one that could not be modernised. «A specific historical arc comes to an end.» (p. 42)

The Earth as a New Actor

So what is the new thing that should enable us to land on earth – in a new relationship with the earth? Latour wants to make this new relationship visible by introducing a new term: the ‹terrestrial›. It is to take the place of the two flight movements, globalisation (the flight forward) on the one hand and localism (the flight backward) on the other. Latour understands the terrestrial as a new political actor, that is, as an effective power that is to participate in our public life, in contrast to the term ‹geopolitics›, in which the earth merely provides the framework for political action. (p. 51) This is the reason why Latour finds the term ‹Anthropocene› unfortunate as a designation for our age. For Latour, the human being is not the main character, and the globe, with its nature and atmosphere, is not merely décor, backdrop, and backstage. (p. 55)

The new politics would therefore have to deal with the earth in a dialogical and mindful way, and it would have to negotiate with the supporters of globalisation on the one hand and those who represent an affiliation to a specific soil on the other. It should be possible to legitimise belonging to a soil without confusing it with the demands of localism – ethnic homogeneity, museumisation, historicism, nostalgia, and false authenticity. Such a reactionary attitude represents a final differentiation, i.e. an end-point that can no longer be developed, whereas the terrestrial is rather characterised by opening. The supporters of globalisation can be shown that their failure to really gain access to the globe and the world can be solved by the terrestrial. The terrestrial may be connected with the earth, but at the same time, it is worldly in the sense that it does not coincide with any border and points beyond all identities. (p. 66)

So in the end, it is not important whether someone is for or against globalisation or localism, «but whether they manage to grasp, hold on to and love the greatest possible number of alternatives of belonging to the world». (p. 24)

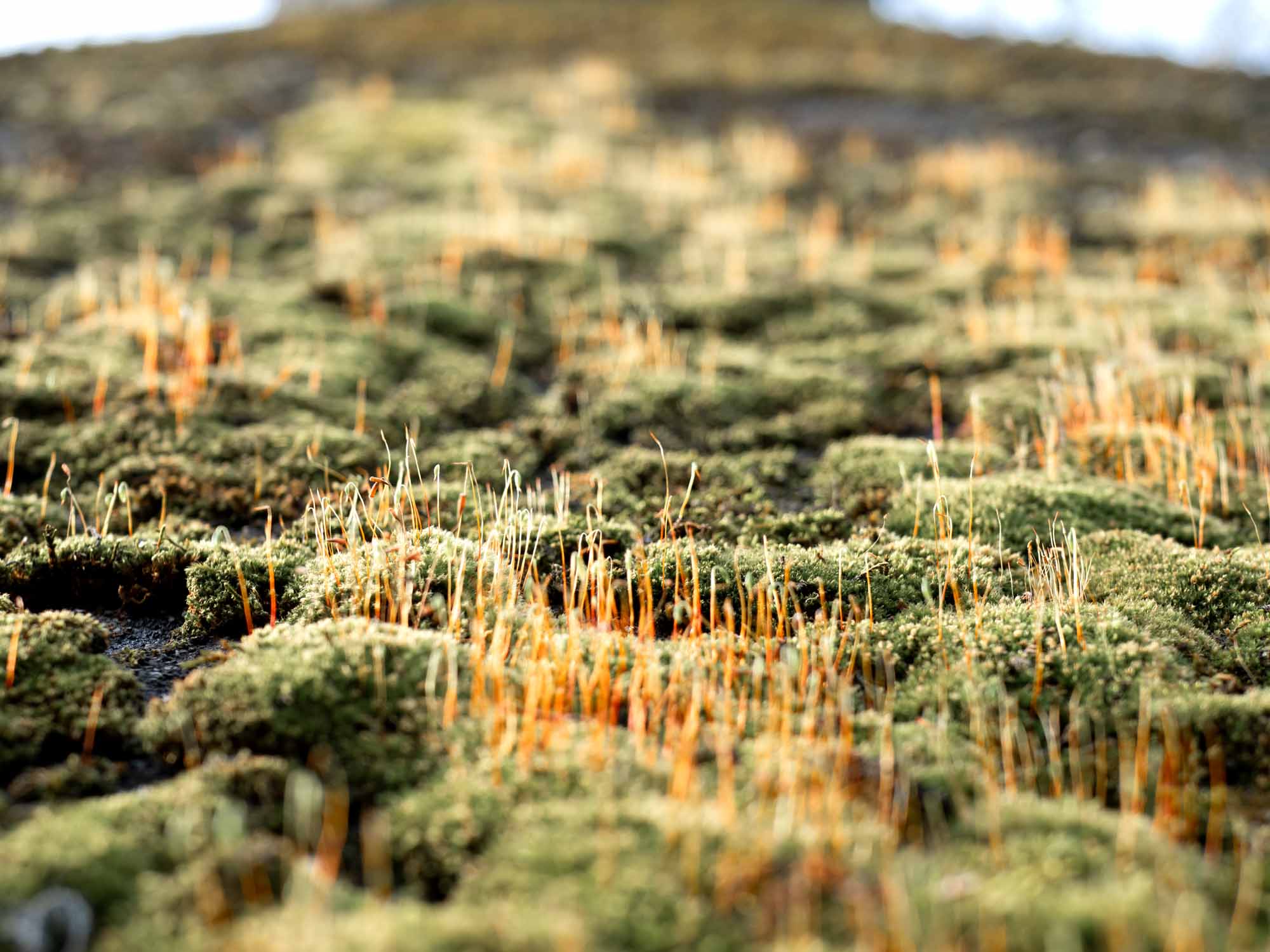

Becoming Humus

Bruno Latour is concerned with the limitlessness and maximum diversity of belonging to the earth, redirecting our attention from ‹nature› to the terrestrial with the aim of ending our disconnectedness from the earth. (p. 96) He reintroduces the old concept of nature through the back door, so to speak: nature as a producer in constant transformation. This gives rise to the proposal to «no longer speak of humans, human beings, but of terrestrials, of the ‹earthbound›, in order to bring out the ‹humus›, ultimately the ‹compost›, that is in the etymology of ‹human›». (p. 101) Ending the disconnectedness means no longer robbing the earth because we can soon migrate to Mars anyway, but connecting more strongly with it by understanding ourselves as humus. If we take this idea seriously and wish to understand the human being as the substance of the soil, haven’t we arrived back at the point where Latour’s critique began, at anthropocentrism? But the question of what the substance of the human being consists of is posed differently from the viewpoint of the soil than from the viewpoint of Sirius. Latour is primarily concerned with shifting the perspective, and it seems to me to be less a theoretical perspective than a perspective of action.

Towards the end of the book, after the analysis of the antagonistic and to some extent hopeless political situation and the introduction of a new pole of attraction – the terrestrial – Latour brings a further proposal for a first step, called «describe first». (p. 109) After the unmasking analysis of the current political world order, the proposal turns out disappointing. Why, actually? I think because the contrast between the massive violence of the world’s failing governments and the proposal to proceed merely descriptively is too great, as if an equally powerful programme seems necessary as a counterweight. But perhaps the solution lies precisely in this, in an exercise in humility: «How can we act politically if we have not first inventoried and measured, creature by creature, head by head, centimetre by centimetre, what the terrestrial is composed of for us? We could then propagate bold theses and stand up for respectable values, but our political effects would run into the void.» (p. 109)

Bruno Latour’s new concept of nature follows on from the pre-modern understanding of a processual nature that moves from within. But it has also become obvious that Latour sees this term as a political one. Nature is no longer there as the basis for politics as a matter of course. Rather, what is needed is a new concept of politics that is oriented towards the new concept of nature. Nature and politics have entered into a symbiotic relationship.

Translation Christian von Arnim

Title image Matt Seymour

Footnotes

- Bruno Latour, ‹Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime›. Cambridge 2018. Since this article is a translation from the German, the page references in brackets in the body text refer to the German version of the book: Das terrestrische Manifest. Berlin 2019.

- Karen Barad, ‹Agentieller Realismus. Über die Bedeutung materiell-diskursiver Praktiken›. Berlin 2012, p. 9.

- Ibid. p. 14.

- Bruno Latour, Peter Weibel (Eds.), ‹Critical Zones. Die Wissenschaft und Politik des Landens auf der Erde›, ZKM Karlsruhe, 2021, p. 18.

- Hans-Dieter Mutschler, ‹Naturphilosophie›. Stuttgart 2002, p. 173.

Thank you!