Rafael Tavares directs the eurythmy in the 2025 production of Faust at the Goetheanum. A conversation with Wolfgang Held.

Wolfgang Held: What did you rehearse today?

Rafael Tavares: We just rehearsed a part of Faust II, the Classical Walpurgis Night scene, when Mephisto encounters the Lamiae, the Greek witches from Thessaly. It’s less about the individual figures than about the space these Greek mythic creatures form around themselves. Mephisto tries to grab them, and they instantly transform their appearance into physicality. That’s what we want to show: that the whole style of movement changes in this moment. At the exact moment of contact, the movement becomes more physical. That’s the tension between drama and eurythmy. Mephisto is horrified by these beings because transformation and metamorphosis, the quality of being alive, are not characteristic of Mephisto and don’t correspond to his nature. He comes from the “north” and is used to everything remaining the same for centuries. He never deals with development.

What’s important to you in terms of eurythmy when working in an ensemble?

When several eurythmists are on stage portraying beings like the Lamiae, it’s not just a matter of movement but of moving the shared space. Eurythmy has the means to do this. It can be portrayed that the five figures representing these Lamiae flow together with one shared quality. The inner sensation, the inward sensitivity of the eurythmists, plays a major role in this. When we use our consciousness to guide our inner sensations so that, through the rhythmic movements, the inner dispositions of the eurythmists soften the space, then we transform the space through eurythmy in a way that can be experienced by the audience. You don’t have to be clairvoyant to see it either; you become aware of it in or on your own body. This happens through the group of eurythmists as a whole. To successfully achieve it, the group has to move together like a choir. In this kind of choral work, it’s important for me to make sure that no one falls out of the group; that we all stay on board. The image we share in common is the bridge.

How does a shared image come about?

In the third act, there’s the chorus of Trojan women at the court of Sparta. There are nine of them on stage, and this gives us the experience of a full and abundant chorus. The movement of each character is important, as together, their movements become a whole through the shared story and the shared image. In this scene, one of the Trojan women, Panthalis, the leader of the chorus, steps forward. We get the first hint of the emergence of individuality. She’s described as the eldest—one could say the most mature in the chorus. She appears to already be on the way towards perceiving herself as an individual. In contrast, Helena already stands there as a single, individual figure. Helena herself comes to a sense of self-consciousness throughout the course of the scene.

There are also prominent eurythmic figures such as Proteus, Euphorion, and Erichto.

Yes, those are great roles, and what matters for me here is how we cast them. The eurythmist creates the character with their whole personality and their understanding of the character’s being. That’s why I think it’s important to give the eurythmists as much freedom as possible. I reflect back to them whether the type of movement is in keeping with the character, and we discuss the role. Still, the eurythmy soloists find their own unique expression. It’s wonderful to see how they all come to life in their own way.

How did you find your way into the choreography?

I first studied the text and Goethe himself. Then I discuss each scene with Andrea Pfaehler and find out how she sees it. I shape the scene from the perspective of my field, eurythmy. I close my eyes, images rise up within me, and I begin to choreograph. This is how the forms, speech sounds, soul gestures, relationships, and much more arise.

What is it like to see the scene on stage?

It makes me very happy because I realize that I have a great team that trusts me and can get into my images. Take the scene of the Aegean Sea, for example. When it’s set up and you can see it, I can tell whether it’s successful by whether I’m drawn into the story, into the scene, from my position standing on the outside, as if I hadn’t created it myself. In a scene like the Trojan Women, the moment when the feelings of the individuals rise to a common emotion is very impressive for me. Today, human beings are very focused on the point, on the individual person, and easily forget the spirituality of the environment. Eurythmy opens our eyes to the side of life that experiences the periphery.

Before rehearsals for Faust, you were involved in Wagner’s Parsifal. How important was that experience for what you’re doing here?

I didn’t do any choreography in the opera production of Parsifal—I was part of the ensemble. This allowed me to observe how corrections and indications from the directors affected the ensemble. What works and what doesn’t work so well? How does the ensemble respond to different ways of being addressed? Bringing together the creativity of individuals and the expression of a group is a fragile process. How do we create a productive atmosphere in rehearsals? Everyone probably sees it a little differently. For me, enthusiasm and calm are important. I like to let myself be carried away by what emerges collectively, while also being responsible for providing a choreographic structure. I also want to offer and help facilitate access to the characters and scene by offering exercises that help us to enter step by step into the inner world of the scene. When everyone is on board, this is clearly demonstrated on stage through a strong collective expression. We have a limited time for rehearsals. This means that I sometimes have to give the ensemble a rough first draft and ask them to go with it for the time being. It’s important that everyone knows what moment we’re in– when we’re searching together, when I’m searching, or when I’m directly giving a form. This sometimes requires patience on the part of the ensemble members because they have to agree to something for which they don’t yet have the full overview.

Where do you see your personal challenge?

I sometimes struggle with the fact that I carry images and moods within me and don’t want to pour them into a form too early, with too much detail already solidified. This can be painful for me because I’m afraid I might cut off our inspiration if some members of the ensemble receive it as a finished, final choreography. The form is only an aid to help us find ourselves in the space. And I search for how much form I should give and how much I should leave open so that I can continue to “paint.” The eurythmists also experience this in their individual parts. If I suggest this gesture here and that gesture there, it’s more difficult for them to find the feeling themselves. I like to keep the balls in the air as long as possible, and that’s certainly a challenge for the team. I try to find the balance.

Is there a particular eurythmy gesture that’s your favorite?

Not really. What I do have is an inner joy when I want to express something artistically and then find the right gesture that draws the audience in. This also involves the “how” of the gesture. I try not to limit myself, but rather to make use of all the great wealth of variety. Take the classic gesture for the sound “B.” There’s the form we’ve all learned, and then there’s an infinite variety of ways to express it. This wellspring of variety is found when I connect with the primal power of “B,” not when I just have the sound “B” in front of me. How do I speak with my eurythmy gesture to represent the image or become the image? In eurythmy, you yourself can be the image and its surroundings: not just a child playing but the sun shining on them, the surroundings mirroring their exuberance—their state of consciousness. I don’t have one gesture that I love, but I do love this process, and we have to dive into this process again and again.

You played major roles in eurythmy as Mephisto and Care in the last production of Faust. Now you’re sitting in the director’s and choreographer’s chair. Is that hard?

And I will still play Care in this production. I’m very happy to be switching to directing because I’m getting to know myself again as a director, in the challenge of developing an image and telling a story. And Faust is not only a great story but also a deeply human one.

Faust 2025 at the Goetheanum

October 10-12th, October 18-19th, October 25-26th

- Production: Andrea Pfaehler

- Eurythmy: Rafael Tavares

- Co-direction: Isabelle Fortagne

- Dramaturgy: Wolfgang Held

- Music: Balz Aliesch

- Lighting: Thomas Stott / Dominique Lorenz

- Set design: Nils Frischknecht

- Costumes: Julia Strahl

Information and tickets faust.jetzt

Translation Joshua Kelberman

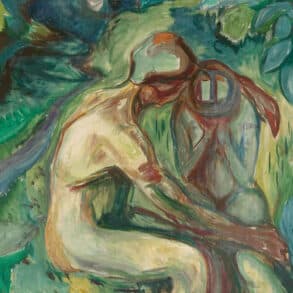

Images from the rehearsals, Photos: Xue Li