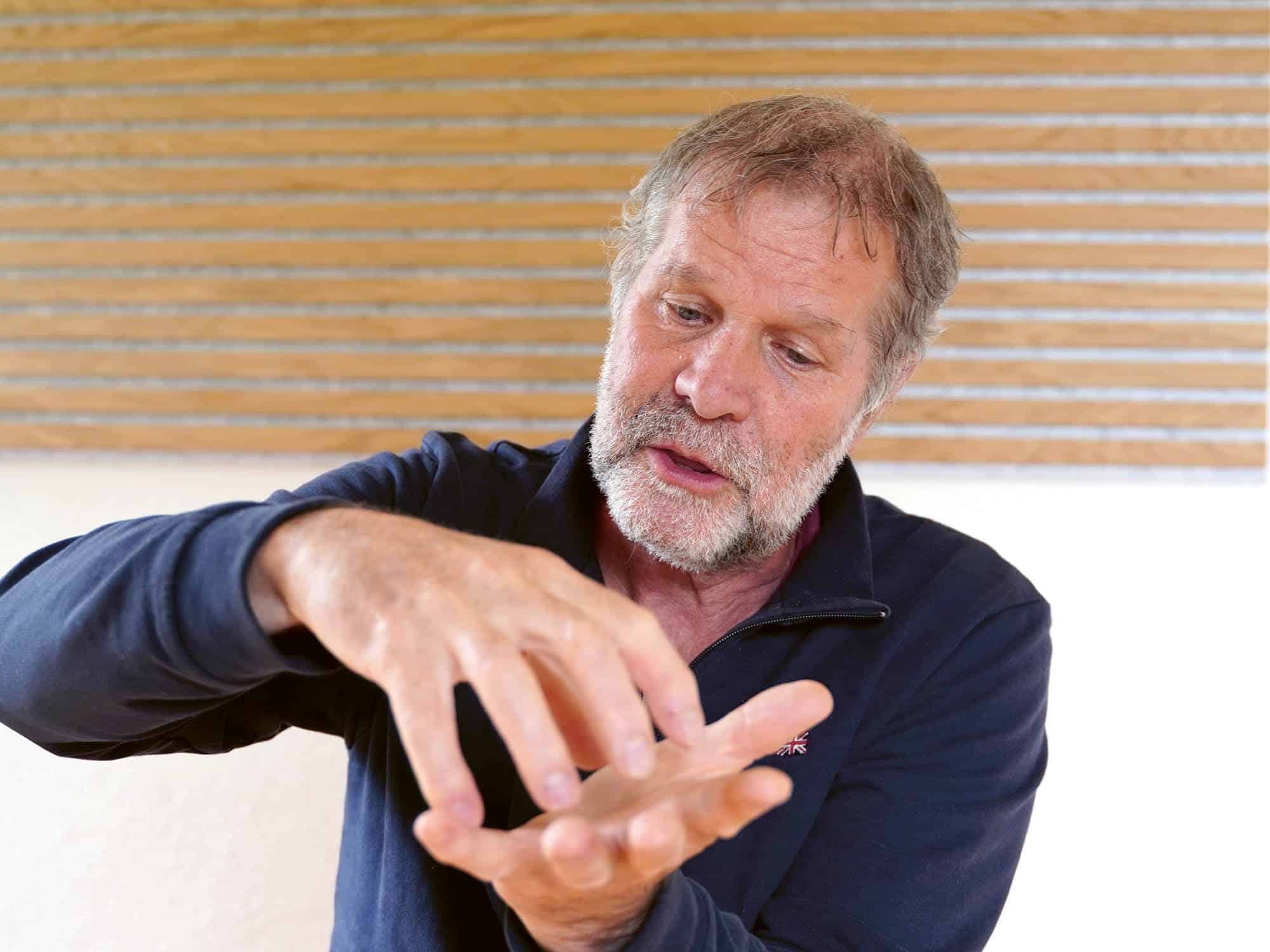

Benno Otter has spent half his life tending the park and gardens around the Goetheanum. Now he gives courses in nature appreciation. Wolfgang Held sat down with him for a conversation about how he brings nature closer to people.

Wolfgang Held: Do you remember one of your first experiences in nature?

Benno Otter: I grew up in northern Holland. I recall looking at the carnations we grew in our garden when I was six or seven years old and thinking they were beautiful. My second experience came during my school days. We had a wonderful biology teacher who gave us the task of creating a herbarium. So, I rode around on my bike and got to know nature properly for the first time. We had to collect a hundred different plants.

A hundred? And you learned all their names?

Yes, we had to dry the plants and identify them in the traditional way, with an identification book. It wasn’t a Waldorf school, but later, when I met my teacher again in high school, it turned out that he was an anthroposophist. He eventually introduced me to anthroposophy, and that’s how I ended up doing a biodynamic training in the Netherlands.

Do you have a favorite plant?

Goethe’s archetypal plant!

Let me ask you the other way around: is there a plant that you don’t find easy to relate to?

The sycamore tree. It just doesn’t seem very natural to me. But what is fascinating about the sycamore is that when its leaves fall in autumn, the new bud is located under the old leaf, and that’s where the new shoot appears. That’s what makes this tree magnificent again.

You can look back on decades of encounters with nature. What is important in an encounter?

Observation, inner calm, and patience. And following the plants through the course of the year again and again, again and again. It’s wonderful that a snowdrop appears in February, followed by crocuses and then foxgloves. So, finding inner peace while observing the plants closely and following the Goethean approach to contemplation. This means to begin with, looking-perceiving everything there is to perceive in a plant, then describing the entire plant, and allowing this observation to sink in.

Do you practice this with students?

Yes, we observe a plant for twenty to thirty minutes. Then I ask: Is the plant within you now, in your body? Check. Close your eyes and see if the snowdrop is within you. Where is it? In your forehead, behind your eyes, in your heart? Most people can describe it quite precisely.

How does this sensation arise?

You close your eyes, and the plant is there. For me, it appears somewhat blurry. The lighter parts are really light, and the leaves have darker contours. This is something we could call imagination. It is the afterimage of looking at something. And then I ask the students to recreate the image of the plant in their minds in the evening before they go to sleep, and then again a week later, and again, and again.

Without looking again at the real plant?

Yes. After a week, I ask the group: Close your eyes. Is the plant still there? That’s the special thing: it is still there! This happens when you look closely, without making judgments, just letting the plant come to you. It’s about letting yourself get caught up in this flow. You can bring a whole series of plants into your soul this way. I recently did a fantastic exercise with the students. We observed a plant from one species and then another. Then we closed our eyes and tried to transform the image of one plant into the other plant in a flowing manner in our minds. It’s not easy. But that’s part of the practice. And then we slowly get into the flowing state of Goethe’s archetypal plant.

I remember this practice with red hibiscus. It was difficult to see the intensity of the flower’s color in my inner eye.

Yes, these inner images are not so clear. For me, they are not photographic. Of course, this can be different for everyone. When I ask, most students describe it to me in a similar way. It’s pictorial but somewhat fuzzy. What is great is returning to the plant in nature and seeing how it has already reached a new stage of growth. First, the flower was closed, now it’s open, then again it’s already a little wilted. Then you, yourself, also enter into the process, into the transformation. This brings us closer to life!

What feedback have you received from your students when you look at plants in this way?

At first, many are amazed that it can have such a lasting impression when you look closely. And then they discover how often we walk past all these plants without forming any image of them at all. It becomes conscious how much we’re missing on a daily basis and how much we could experience through a deeper relationship with nature if we only took the time to do so once a week.

Does something change in our own features and how we are perceived by others? How does observing others change us?

I usually begin a seminar with a preliminary exercise. I ask the students: Close your eyes. Observe your physical body right now. How are you standing? Can you feel your joints? This allows you to arrive in yourself. Then I do the same thing with the water inside them: Can you feel the watery element, the streaming inside? That’s related to the etheric. Third, focus your attention on the flow of air—your breath. It’s especially important to direct your consciousness to your breath. This is because there is always a brief interruption in your attention when you breathe in and out. Rudolf Steiner describes beautifully how, in the act of observation, the astral body goes out like the out-breath. He compares this to nighttime, when our astral body goes almost entirely outside of the body, lying in bed. During the act of observation, there’s a very similar “nighttime” experience. Fourth, warmth: How is warmth distributed throughout your body? Only after these preliminary exercises do we then approach the plants and get a first impression. If it’s a flower bed or something similar, we first just let it sink in for a moment; then we look more closely and ask more precisely how the four elements are distributed in the plant before us. Our body, our whole being, is an instrument whereby we can experience something outside, where the elements are at home. We begin to feel the plant—we have calibrated ourselves a little, like an instrument. Through such practices, we are prepared when we first encounter the plant.

Can you tell whether students are succeeding in entering into this relationship? How does this manifest in the person themselves?

First of all, I see if someone is able to calm down. There are some in the group who manage this wonderfully and others who find it difficult to get started. When we are able to bring ourselves to a feeling of calm, our facial features relax. I interpret this as a kind of arrival, a connection, an immersion.

Today, we’re used to seeing the illuminated screens of digital devices—the light comes towards us. Is it noticeable that we therefore have to overcome a certain resistance when looking at plants?

That’s true. There have also been students who said to me after six months, “What you’re doing is wonderful, but I don’t understand it. I can’t find my way into it.” And then, I talk to them, of course. You actually have to get away from your head, detach yourself from the intellect. Some people find it difficult, while others are incredibly grateful for the opportunity to have this experience. It depends on where and how you grew up, whether your reason gets in the way or not. It’s also true that anthroposophy can get in the way. You know so much, and then you look at a dandelion and think, “That’s too simple. That’s the ordinary world.” But this ordinary world is extremely exciting! Here are a few lines by Rudolf Steiner: “When you look into the eyes of another, you get a glimpse of their soul. Likewise, when you look deep into the heart of a flower, you get a glimpse into the soul of the Earth.” That’s wonderful! And this verse builds a bridge from the human face to the face of flowers and then to the flow of the Earth.

Is there a difference in approaching a tree versus a flower?

Let’s take beech branches as an example. We take a shoot from the branch, remove all the bud scales, and lay them out in a row. Then we do the same with the leaves, adding one leaf after another. And then we try to imagine what will happen to the branch next year: how will it continue to grow? We also go backwards and imagine the branch two or three years ago. This reveals the laws of growth. It’s amazing! If we look at the growth from one year, it doesn’t grow any further; the span from one shoot to the next doesn’t increase. That part of the branch gets thicker but not longer. It’s such a wonderful law. If the branches kept stretching out longer and longer, the trees would have snapped long ago and would have had no stability. When we look at trees like this, we get a sense of permanence and of what happens year after year. This way, we become conscious of the entire history of the tree from one single branch. I then collect branches from very dry places in the forest, where the tree grows very slowly, and from damp places, where there’s a lot of growth. This allows the students to see that each branch also reflects its environment.

This reminds me of the writer Henry David Thoreau, who describes his two years in the peace and tranquility of nature in his book Walden; or, Life in the Woods.

That’s why it’s so nice to walk through a forest fully awake and attentive: you experience duration. You experience it in the life of the forest, the continuous living of life.

You have been managing the Goetheanum Park using biodynamic methods for more than thirty years. What is your experience of this “managing”?

I feel it most clearly in the fact that the park has become an organism, that it has really become a unified whole, more or less. That has changed a lot over the last forty years. The guiding principle of biodynamic farming is to form an organism with an eye to its individuality. That’s why I often say when I go to the nursery, “Good morning, how are you today?” So, when I come here from outside, I feel, “Now, I’m ‘inside’ it.” That’s the organism. Of course, the nursery as an organism within a greater organism is also part of this. That’s the social organism, and it has to all work together.

What do you consider to be Rudolf Steiner’s most important indication for observing nature?

I’ve already quoted him on looking, and I’d like to add something from Goethe’s scientific works. “The formed is immediately transformed, and if we want to gain a living view of nature, we must keep ourselves as mobile and malleable as nature herself is, following the example she sets us.” It’s about this immersion. When you really see the plant world, or follow the peony through its metamorphoses—it’s incredible what happens there—and when you try to enter into this mobility, then you yourself become mobile, in your thinking and in your feeling.

Like recognizes like?

Yes. If you manage to empathize with this stream of transformation, then you are in the metamorphosis, as Goethe describes it. You see the individual leaves, which are all so different, but what happens invisibly between the leaves is the most important thing. The most important thing is to see what you cannot see! And then you are in the etheric stream. The most important thing for me in my work with people is that they feel, “I am in this stream.” Our etheric body loses its force through intellectual activity and the media. We draw new strength from observing plants. You can also do this by simply going for a walk. Then you are also in this etheric stream. When I go for a walk, I can immerse myself in it. I can also do that unconsciously. That also has an effect.

Do you sense new skills among the students?

Yes, I sense a great openness among the students who come here, as well as in other courses and guided tours. I experience this very strongly, and it’s a different kind of openness. We hear about disasters and climate change, species extinction, and other negative scenarios. This atmosphere of loss creates a longing in our souls. We would like to have a relationship with nature.

What surprises you most when you encounter nature?

The incredible, dynamic creativity that Goethe described: when I look at a plant and see that the next plant is completely different, yet still subject to the same laws of nature. This diversity is a miracle. I encounter it every day, and every day I’m amazed in some new way.

What does it mean for Nature when we turn toward her?

She feels happy! When I give observation lessons and make plant cuttings, some participants object to what they perceive as harmful to the plant. Then I say: whenever you cut something, Nature rejoices. Rudolf Steiner describes it as mowing with a scythe. A delight goes through the Earth. I can literally feel it. When we sit in the park with a group of fifteen people and gaze reverently at nature, it’s simply a moment of happiness for the people and also for nature. When you hike through the Alps in summer, when everything is in bloom, after six or seven hours, you’re completely tired out but totally refreshed within. What plants show us, as Rudolf Steiner describes it, are the feelings and thoughts of the Earth. We connect with them simply by truly looking at them.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Title image Benno Otter. Photo: Wolfgang Held