In 2020, a fragment of a previously unnoticed text by Rudolf Steiner was published for the first time. It contains important insights into the human ability to perceive the ‘I’ of another.

An exemplary volume of the complete works of Rudolf Steiner in German was published containing numerous previously unpublished treatises and fragments, including a short fragment on the difference between human and animal organisms.1 The original dating of the fragment was between 1903 to 1909, but it is more likely to have been written around 1910.2 It contains ideas of significance for anthroposophical researchers and contributes something new to the deepening of the anthroposophical perspective on the human being.

In the fragment, Steiner emphasizes that the reason human beings can experience themselves as independent spiritual beings is that we can “extract” the spirit from our physical being due to the partial mineralization of our physical constitution. We then experience a more conscious “spiritualization.” This unique potential for spiritualization that is available to human beings is connected with two factors: on the one hand, the human being in their present stage of evolution is “less permeated by [the spirit], but can participate in [the spirit];” and, on the other hand, the human being has certain “life conditions” surrounding them that then allow them to encounter a “sensory world.”3 Consequently, human beings can participate in the external world to a higher degree than animals, whose organization remains more permeated by the spirit. Thus, “animality is much more organically self-contained than humanity,” and its life is purely a life of the soul. In contrast, “the human being is spirit and soul. . . . [T]he human being shapes their organism by way of the spirit and lives with their organism in the world as spirit.”4

‘I’ and Form

After these introductory remarks (which are only briefly touched upon here), Steiner characterizes the human form in a way that anticipates fundamental aspects of his later, more detailed investigations into the sensory organism.

According to Steiner, human beings can experience their own ‘I’ and the ‘I’ of another because the human form [Gestalt] reveals a certain balance of forces, an equilibrium, between the brain/head and the spinal cord. Based upon that, “the relationship of hands/arms to feet/legs. . . . But only in a kind of dim consciousness do human beings experience this balance of forces (and all that follows from it) as the principle that sustains their ‘I’. And when they stand face to face with another human being, they perceive the other’s ‘I’ directly in this form. Both perceptions—that of one’s own ‘I’ and that of the foreign ‘I’—live at the baseline of ordinary consciousness in the same way that experiences of sleep consciousness do, except that sleep consciousness alternates with ordinary consciousness, whereas this dull consciousness of the ‘I’ is always present alongside our ordinary consciousness.”5

The fact that we experience the ‘I’ in this “balance of forces” in the human being and not through the direct shaping of spiritual thought, enables us to have “a special power of soul—the ability to think.” In other words, the human organization is not formed in such a way that “thought flows as a whole into the organic form.” Humans carry, so to speak, the essence of thinking, a thinking “without form, as a life of thoughts weaving within themselves.” Thus, “the human soul… can live a life of its own, free of the body, without form.”6

Sense of the ‘I’ and Free Will

These statements from the fragment provide further evidence that, years before the statements he makes in his lectures, Steiner was investigating our organism’s sensory activity connected with the sense of the ‘I’, i.e., the perception of the ‘I’ of someone else during physical encounters between human beings.7 In the years around 1909, he’d already related the activity of the sense of the ‘I’ with the archetype of human perception, and thus with human sensory activity.8 He eventually explicitly connects this activity with the human form, viewed as proceeding from the head (referred to there as the organ of the ‘I’-sense), in the lecture of September 2, 1916.9 Here, he doesn’t offer any further explanations about this connection, but he does in the fragment that we’re discussing. Then, in the lecture on August 29, 1919, Steiner explicitly connects the activity of the ‘I’-sense (its longest surviving description is in that lecture) and the perception of the foreign ‘I’, with the alternation of sleeping and waking consciousness, in the same way as he does in this fragment from nearly ten years earlier.10

The new idea given in this fragment is that the perception of one’s own ‘I’ and that of the other is traced back to a single common source: the equilibrium of forces in the human form. We find here a complement to Steiner’s later statements where he describes how the perception of one’s own ‘I’ is solely connected with the sense of touch and the organic context of the touch sense.11 In the fragment, the human form is designated as the basis of ‘I’-perception, both of the purely inner experience of one’s own ‘I’ and the opening of the ‘I’ to the perception of the other’s ‘I’ (initially only in their external appearance). In other words, the human form, the human gestalt, brings about the concordant, dynamic unity of inner/inwardness and outer/outwardness, precisely in relation to the two decisive encounters in a human life: the encounter with our experience of our own ‘I’ and our encounter, within our perceiving ‘I’, with the presence of the ‘I’ of another.12

Out of this balance of forces, the equilibrium that permeates the human form, we human beings can also reveal our free will in the world. During the act of perception, a human being is conscious that “as a spiritual being, the human being stands with will transformed into action in the same world where they stand with their ‘I’ through the experience of equilibrium, an experience of the balancing of forces. As a spirit, the human being lives in the sensation of the world’s equilibrium and in their will-determined actions.”13

To formulate it another way: the balance of forces in our human form enables us to be free beings, both in terms of being an ‘I’ and being in the world. Our will is free because it can act outside the body to “inhibit or promote the world,” exerting itself “in objective spiritual existence.”14 The will of human beings is not a “direct result of the body’s organization or the body’s conditioning by the external world. In human beings, the experience of the external world conditions the will. In the will, human beings switch off their bodily organization. Through their will, they accomplish what has nothing to do with their bodily organization.”15

Consequently, the will can reveal the workings of the free ‘I’ and thus is freely able to will what is good. The “Warmth Meditation” given in 1924 is an archetypal example of this fact.16

The ‘I’ as the Squaring of the Circle

“In ‘I’-consciousness, the spirit lives in the specifically human balance of forces. The spirit lives in the physical world, but only through forces that are effective in the physical world.” With this, Steiner’s fragmentary sketch breaks off.17

“Fragment” means literally “the result of breaking off or discontinuing.” However, this break does not imply an abandonment of the path of research Steiner was engaged with here. This path is so important to him, so essential, that not long after writing this fragment, or perhaps even around the same time, he wanted to write a book with the simple title, Anthroposophy. In many respects, the unfinished book sounds like a continuation of the last words of this fragment, as well as what is only indicated implicitly in the fragment: that sensory perception and the sensory organism are prerequisites for a deeper spiritualization of the human being. They are the decisive prerequisites for encountering the sensory world, which, as indicated above, is linked in this fragment to the deeper possibility of spiritualization in the human being.18

The book, Anthroposophy: A Fragment (in particular, chapters 3 and 6) is an attempt to deepen sensory perception and the senses by proceeding from the ‘I’ and the experience of the ‘I’, and to make the senses more and more understandable as a field wherein the free life of a spiritual being can become present in the physical world. Despite the later elaborations that Steiner devoted to the sensory organism, one decisive indication in the new fragment discussed here remains unique (as far as I’m aware): The connection between both perceptions of an ‘I’—one’s own and that of another—and the relation of forces that determine, in the human form, the relationship between the brain/head and the spinal cord on the one hand, and the relationship between the hands/arms and the feet/legs on the other.

I find it absurd to think that, at some point, Steiner no longer considered this connection to be consistent or coherent. It’s more likely that he didn’t take it up again because it points to the extraordinarily complex topic of squaring the circle, and also, perhaps no one asked him about the relationship of this topic to human beings. As Kaspar Appenzeller shows, the answer to this question becomes apparent in the fundamental relationships of the human form (to which Steiner refers in this fragment, unknown to Appenzeller, of course!), which are also evident in Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.19 The human form represents a transcendent, non-closed off, unending number—the number of the circle, pi (π). The human form does not express a “dominating or subjugating way of thinking,” but instead represents a balance or equilibrium of forces that make human beings essentially less complete, simply by virtue of their organism, than other living beings.

Humans as an Open-Ended Present

This organic open-endedness enables human beings to live as free individuals, as free spiritual beings in the physical world. Attention to this open-endedness as the reason for the presence of the ‘I’ in oneself and in other people is perhaps the most fruitful legacy, the really new thing, that we owe to this fragment briefly explored here. More and more authorities and trends of our time would have us believe that striving for ever more complete unity in all areas of life will bring peace and happiness. This is increasingly to be achieved by replacing the sensory organism with technology, thereby relinquishing the free activity given by the human form—what Steiner sought to deepen in a revolutionary way as the ‘I’-organism, the ‘I’-form, the ‘I’-gestalt.

But would this ever more complete unity that is striven for today not actually be an increasing renunciation of our present and future, an increasing pull solely toward the past? What is finished and completed can only be a result of the past! Are these trends, perhaps, just a clever mask that portrays this kind of completeness as exactly what we’re all longing for and hoping for our future? Can the present really occur in any other way than as a necessary creative break from the past with its onward rolling, indefinite continuation, meaning no real future at all, but only a spiritless return of the same in some increasingly closed-off solipsistic unity? Only when the past can and is allowed to become a fragment by way of our free, creative break from its inertia, that is, only with a discontinuity, does the present actually become possible in this physical realm. Thus, the present becomes the threshold to a real future of what is truly earthly: the threshold to a coherent transformation that can resound as the voice of the ‘I’, whose presence, the presence of human beings, can never occur as something closed-off, as merely a square or merely a circle.

From a fragment, something new emerges: “I as the present.”

Translation Joshua Kelberman

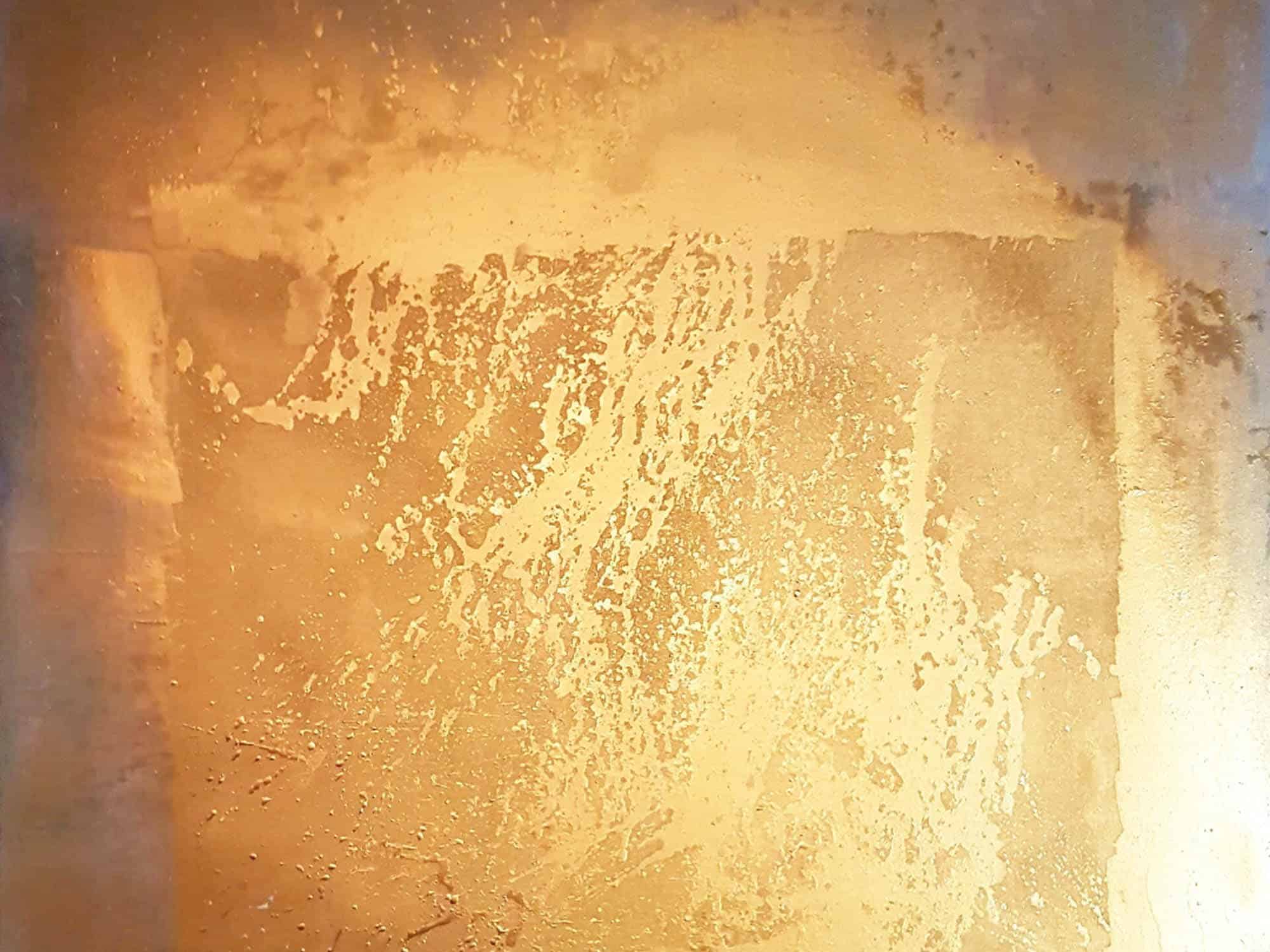

Image Irene Melito, Aurea Quadratura [Golden quadrature], oil and pigment on canvas (100 x 120 cm), 2023.

Footnotes

- Rudolf Steiner, Nachgelassene Abhandlungen und Fragmente [Posthumous essays and fragments], GA 46 (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2020), fragment 50, pp. 486–498.

- On November 10 and 17, 1910, Steiner gave lectures in Berlin on “The Human Soul and the Animal Soul” and “The Human Spirit and the Animal Spirit,” in Rudolf Steiner, Antworten der Geisteswissenschaft auf die großen Fragen des Daseins [Answers of spiritual science to the great questions of existence], GA 60 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 1983).

- See footnote 1, p. 489.

- Ibid., p. 490.

- Ibid., p. 492.

- Ibid. and p. 494.

- On the ‘I’-sense, see: Salvatore Lavecchia, “Ich-Sinn und Ich-Bild. Wahrnehmen jenseits von Innen und Außen” [The Sense of the ‘I’ and the image of the ‘I’. Perception beyond inner and outer), Stil 46, no. 4 (2024), pp. 71–77; and Sebastian Lorenz, “Der Ich-Sinn und sein Organ. Anthroposophische Sinneslehre und heutige Neuropsychologie” [The ‘I’-sense and its organ. Anthroposophical theory of the senses and contemporary neuropsychology], Stil 44, no. 1 (2022), pp. 35–41; Detlef Hardorp, “Rudolf Steiners Wirken um das Jahr 1910: ‘Von den Anthroposophie-Vorträgen des Jahres 1909 zum Fragment gebliebenen Buch Anthroposophie (1910). Eine Untersuchung der Textgenese im Lichte bisher unveröffentlichter Notizbucheintragungen’” [Rudolf Steiner’s work around 1910: “From the lectures on anthroposophy in 1909 to the fragmentary book Anthroposophy (1910). An investigation of the genesis of the text in the light of previously unpublished notebook entries”], Archivemagazin, no. 13 (2023), pp. 74–132, esp. pp. 101–124.

- See Anthroposophie. Ein Fragment, GA 45 (Dornach: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2002), p. 186; cf. Rudolf Steiner, Anthroposophy. A Fragment: A New Foundation for the Study of Human Nature, CW 45 (Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1996); see also Salvatore Lavecchia, “Anthroposophie als Revolution der Sinne” [Anthroposophy as a revolution of the senses], Das Goetheanum 25/26 (June 21, 2019), pp. 6–9; Salvatore Lavecchia, Ich als Gespräch: Anthroposophie der Sinne [‘I’ as conversation: Anthroposophy of the senses] (Stuttgart: Verlag Freies Geistesleben, 2022) pp. 37–43.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Riddle of Humanity, CW 170 (London: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1990), lecture in Dornach, Sept. 2, 1916.

- Rudolf Steiner, The Foundations of Human Experience, CW 293 (Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press, 1996), lecture in Stuttgart, Aug. 30, 1919.

- Cf., for example, Rudolf Steiner, Europe Between East and West in Cosmic and Human History, CW 174a (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2024), lecture in Munich, Nov. 29, 1915; see also footnote 9 above.

- See footnote 8 and 10; Rudolf Steiner, The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. Fundamental Features of a Modern Worldview: Results of Soul Observation According to the Natural-scientific Method, CW 4 (Tiburon, CA: Chadwick Library Press, 2020), appendix 1, “Addendum to the Revised Edition of 1918”; also known as The Philosophy of Freedom.

- See footnote 1, p. 493.

- Ibid., p. 495.

- Ibid., p. 496.

- Rudolf Steiner, “Meditation for Helene von Grunelius, Autumn 1923,” in Understanding Healing: Meditative Reflections on Deepening Medicine through Spiritual Science, CW 316 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2013), p. 202–203; also in Mantric Sayings: Meditations 1903–1925, CW 268 (Hudson, NY: SteinerBooks, 2015).

- See footnote 1, p. 497.

- Ibid., p. 489.

- Kaspar Appenzeller, Die Quadratur des Zirkels: Ein Beitrag zur Menschenerkenntnis (Basel: Zbinden, 1979). For the Vitruvian Man, see, for example, Wikipedia. “Vitruvian Man,” last modified October 15, 2023.