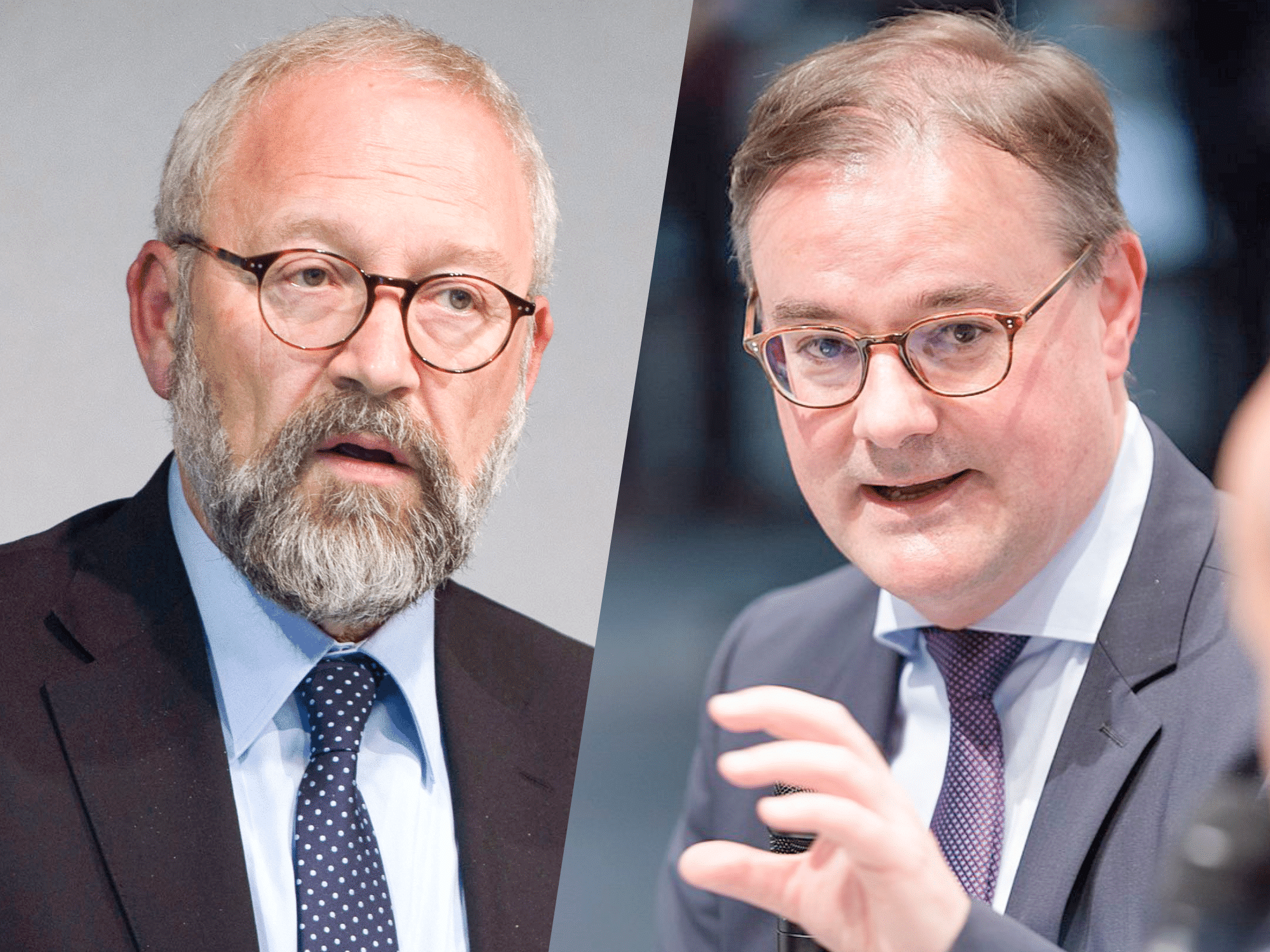

In the third year of the Russo-Ukranian War, historians and political scientists are speaking out and offering their analyses in the midst of speechlessness and slogans. We take a look at two of them here.

“If you want to read into the future, you have to leaf through the past.” Historian Herfried Münkler opens his book Welt in Aufruhr: Die Ordnung der Mächte im 21. Jahrhundert [World in Turmoil: The Order of Powers in the 21st Century]1 with this quote by André Malraux. Münkler, whose formidable works on the Thirty Years’ War and the First World War outline turning points in European life and consciousness, moves into the present with this volume, published last year. Like others, he describes the current times as an awakening into another world.

The East-West confrontation in the 1980s, with military armament and retrofitting, revealed a stagnant and, therefore, predictable order. According to Münkler, no attention was paid to the many other conflicts, but after the fall of the Wall, people held on to the aspiration that society had arrived at a state of stability. “Economy instead of military” became the slogan. It was a judicialization of politics; the Court of Justice in The Hague and the UN tribunals would replace weapons. According to Münkler, the narratives of the powers—democracy, freedom, and prosperity in the West, equality and justice in the East—had formed a stable opposition. The US wars in Vietnam and Korea and the suppression of freedom movements in the GDR or Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union are examples of the flimsiness and fragility of these narratives. When Slobodan Milošević, a key figure in the war in Yugoslavia, was indicted for crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court in The Hague on May 27, 1999, the turn of the century was gifted with an image of the dream of non-violent coexistence—which was lost barely a breath later with the attack on the Twin Towers in New York and the US response to the Iraq War.

Münkler develops the concept of moral laxity. American strategists in the 1990s adopted Edward Gibbon’s opus about the decline and fall of the Roman Empire as their own. The historian described how during Rome’s last long period of peace, under Antonius Pius and the subsequent emperors in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, the empire lost the strength to assert itself against incursions from the steppes by Germanic tribes and Huns. This legitimized and motivated the staging of armed conflicts all over the world, even at a time when there was no other power comparable to the USA. In this way, Münkler uses large historical and small contemporary arcs to paint a picture of a world in turmoil. In the Saarland Democracy Foundation podcast, he says, self-critically: “We [Europeans]—and I don’t want to exclude myself—have lived for a relatively long time with the idea that peace and freedom are, in a sense, the just reward for having become so sensible. And in this excess of complacency, we have forgotten that peace and freedom have a price.” We don’t get peace just by being peaceful—we also have to create and defend peace. This also applies to freedom. It always has to be reclaimed and strengthened—both internally and externally. To do this, we have to have the ability to stand up for our own values with conviction and—as can be seen in Ukraine—with a willingness to make sacrifices. Münkler takes the words of Joschka Fischer, who replaces Olaf Scholz’s “changing with the times” [Zeitenwende, meaning turning point] with the term “breaking with the times” [Zeitenbruchs].

A second book adds to this picture of confusion and fragmentation. The Freiburg historian Jörn Leonhard deals with the question that everyone is probably asking themselves and is silent about: How can the war in Ukraine be stopped? Über Kriege und wie man sie beendet—Zehn Thesen, [On wars and how to end them—Ten theses]2 is the title of Leonhard’s book. He echoes Malraux’s words at the beginning and compares the Russian war with previous conflicts and armed conflicts. The first thesis states, “The nature of a war determines its conclusion.” This means that the more complex a war is, the more difficult it is to make peace. Russia’s war of aggression is now a war of nation-building, because the Russian invasion is intensifying Ukrainian identity. The war is also a religious war because Ukrainian and Russian Orthodoxy are separating. It is a war about values (democracy and autocracy), it is a media war, and it is a global conflict about economy and energy. The more such elements come into play, the more difficult it is to come to peace.

Thesis No. 2 sounds familiar: “The longer a war lasts, the more difficult it is to contain.” At the Battle of Sedan, he shows that there is no decisive confrontation. Pearl Harbor did not bring about the end that Japan had hoped for, any more than did the use of poison gas in the First World War. Leonhard adds that wars never turn out the way the attackers and defenders think they will. Thesis No. 5 is also depressing: according to this one, resources determine the tipping point of a war but not the discernment for peace negotiations. By 1942, German resources were exhausted, but the war got worse after that. History shows that sanctions do not shorten the duration of war.

The absurdity of war also applies to Thesis No. 10, according to which a victory does not necessarily mean a win. Prussia suffered a heavy defeat against Napoleon in 1807. In the peacetime that followed, the Prussian state implemented a wealth of reforms, similar to Germany and Japan, which arose from their defeat in the Second World War as democracies, so that concepts of “victory” and “defeat” lost their distinctiveness in peacetime. Winning in peace, in this way, is wished for Russia. However, Leonhard formulates what makes this path to peace so difficult in Thesis No. 3, “Rotten Peace” [Fauler Frieden,] and reminds us how the Versailles Peace Treaty, after the First World War, laid the seeds for an even more terrible war. Theses No. 7 and No. 9 are a warning: “There is no peace without communication, and those who humiliate the defeated turn peace into a ceasefire.” He adds: “Once the treaties are signed, the work on peace begins.” A lesson from both books—often found between the lines—is that the longing and insight needed for peace grow in conflict. Even while your fist is still clenched, you start to envision peace. This opens the heart, and the heart loosens its fist. Books like these do that.

Translation Laura Liska

Image Left: Herfried Münkler (Humboldt University, Berlin) Photo: Stephan Röhl CC BY-SA 2.0 DEED. Right: Jörn Leonhard, Frankfurt Book Fair 2018. Photo: Martin Kraft, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE License agreement: Legal code CC BY-SA 3.0