The World Teachers’ Conference dedicated both a forum and a working group to education for a digital world. Children and young people have a sense that the fundamental changes that are taking place today in nature, in humanity, and in society will only come to fruition in the decades to come.

Young people are increasingly aware that climate change, migration, and digital transformation will impact their biographies, but they don’t know how. In earnest but sometimes irritating and cynical ways, they are certain that they will have to live differently from us. They are looking at an open, challenging future, for which the life of the adults around them and the past offer little orientation. However, a look at the past shows that technological revolutions are not only about technology. The industrialization of the 18th and 19th centuries resulted in global upheaval rather than a more elegant, technologized variation of the old society. The introduction of the steam engine paralleled the birth of democracy. It brought world trade but also extreme forms of slavery and exploitation of nature. It also highlighted the misery of laborers that has since assumed terrible proportions, and it has consequences that are apparent in climate change, war, and global migration. Industrialization led to a new image of humans as autonomous beings: the special nature of childhood was identified, compulsory schooling introduced, and schools were regarded as places of social balance. At the same time, schools became increasingly industrialized, equipped like machine halls, and organized like factories—from the architecture to the basic structures (in grades or years) to standardized outcomes.

Education has since become a mirror of the ambivalence of industrialization, with efficiency, learning targets, and preparation for the labor market on the one hand, and, on the other hand, energetic attempts to make education more individual, fair, inclusive, and humane, in order to mitigate the industrial aspect. Only a small part of industrialization’s technological revolution is in fact technological. It has affected the world and humanity in all aspects of life.

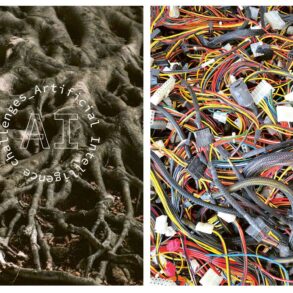

Sub-Nature and Super-Nature

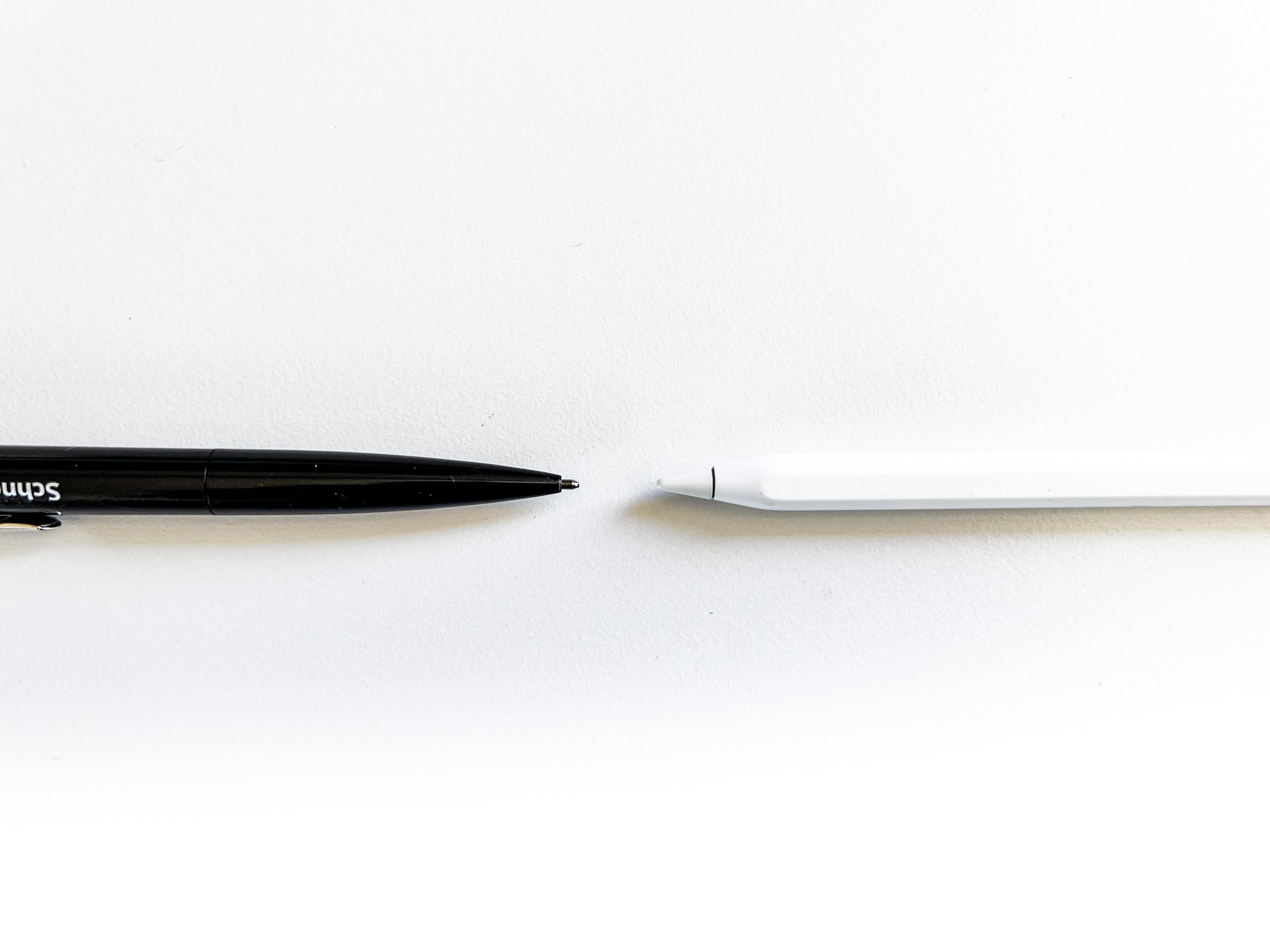

Steam engines and railroads were alien and new when they were first introduced to a rural world, but soon came to form the technological foundation of urban life. Digital devices were equally alien and new when they entered urban life at the end of the 20th century, but in the 21st century, digitalization has become so widespread that we depend on it. From basic provisions to highly responsible tasks, everything relies directly or indirectly on digital infrastructures today. Since the 2010s, digital technologies have become ubiquitous in everyday life, forming an often seamless environment for our work, our relationships with others, entertainment and leisure. Just as industrialization created the environment of the modern city, digitalization has created our digital lifeworld.

Email, social media, video conferencing, learning platforms and chats are places where presence of mind is required so one can understand decision-making processes, respond, cultivate friendships, carry out tasks, form judgements, and assume responsibility. In this space, ideas, fantasies, illusions, and memories—which manifest as texts, icons, films, photos—as well as the responses and references to them, constitute the substance in which consciousness is present. Digital media could thus be understood as “ideation machines” that create a space where our minds can comfortably move and interact with the products of our inner life. These technologies allow us not only to be in the world of images, ideas and memories as we produce them ourselves through mental activity, but also to live and interact in them almost without being active ourselves.

The architecture of these digital spaces has become so dense in the past ten years that being in them has become the full-time daily norm for many people in the previously industrial nations. The digital environment that has become the lifeworld that our mind inhabits can be described as a technological form of “super-nature”. It forms a counterpart to the lifeworld of the industrial machine age that Rudolf Steiner referred to as “sub-nature”. According to Rudolf Steiner, living in sub-nature causes us to become separated and alienated from essential aspects of the world—in particular nature, other people and the meaning of life—in a way that threatens our very humanity.

Alienated from the Body

Just as modern industrial work and city life has fundamentally changed our relationship with the world, living in the digital lifeworld fundamentally changes how we relate to our own being, to our body, since the mind can now permanently inhabit an imaginative world without being active itself. From the point of view of this “super-nature”, this digital lifeworld, our own body becomes part of the world of things: I’m no longer the one who looks at the world and generates an inner image of it, but I look at my physicality from the outside. The morning verse in Waldorf schools—“I look into the world”—no longer applies because I look at myself. I form a picture of how my body appears in the world; I look at myself as others do. The selfie and TikTok culture are symptoms of this change that objectifies our body. The digital presence makes us look at our body from outside—a technologically induced, permanent viewing of myself that makes my body an object of control and optimization.

Living in digital spaces also means living with possibilities. Everything seems possible at any time. But when everything is possible for me at all times, there is no attachment, no reification, no biography in the actual sense of the word: nothing is inscribed, nothing writes itself into the text of my life. It can be described as a platonic state, for Plato wanted to go back in thinking to the prenatal state, where ideas are not yet distorted by bodily experiences. But biography unfolds through reification; it requires a text of life to emerge as I write something irreversibly into life. Digital life can therefore be seen as a state that takes us to a prenatal state and keeps us from experiences that inscribe themselves in us. Maybe this is why so many young people, even into early adulthood, find it difficult to know what they want “to do in life”. Entering one’s own becoming in connection with the becoming of the world—which is something that belongs to the ‘I’— cannot happen in this “platonic state”. Identifying with one’s own physicality for this lifetime becomes an existential threshold and decision.

Another challenge posed by a digital lifeworld is our relationship to other people as unique others. Without active resistance on our part, the digital environment holds us in a “filter bubble” where algorithms make sure that we always see what we like and what already corresponds to our inner life. Jean Baudrillard describes the digital world as “hell of the same” because we always experience a world that we already are: I am shown what is like me—nothing else. This brings up the question of character building, for, as Martin Buber or Emmanuel Levinas also say, we develop our own self in the experience of the otherness of others.

Being Body as a Pedagogical Task

The digital lifeworld therefore becomes a challenge for essential development in childhood and youth: to experience the sensory world with the body as the world with and in which we live, taking hold of the lived life as biography and the possibility to meet others in their unique otherness.

In the light of Waldorf Education and its anthropology, these possibilities rely on becoming autonomous (“birth”) and independently taking hold of three bodily dimensions: physical body, life body, and soul body. As the digital world becomes the primary environment, being in the body no longer appears as a given, natural development to be accompanied by education. These births, which enable us to be body, to be in the world, become a cultural task for which responsibility needs to be assumed. In the coming decades, they will probably become the subject of intensive cultural, ethical, medical, and pedagogical debates, in the way conception, pregnancy, and birth used to be in the 20th century. In the future, education should understand these “births” as a task, make them possible and give them a cultural, humane form.

Early 20th century education saw itself as a contribution to human freedom and to educational fairness in the precarious environment of industrialized lifeworlds. It was precisely in response to this that the first Waldorf school was founded as a school for the workers of the Waldorf Astoria cigarette factory. The corresponding pedagogical response for the 21st century that absorbs and pedagogically addresses the consequences of the digital transformation, is yet to come. Even though much is being done to counteract the consequences of digitalization in schools, to learn about them, and to acquire competence in dealing with digital media, a pedagogy still needs to be developed that acknowledges and transforms the far-reaching consequences of our digitalized lives and promotes humanization.

Translation Margot M. Saar

Photo Sofia Lismont