Whether God, Buddha, Krishna, Christ, or something else, there is an active presence that is moving humans toward truth, beauty, and goodness. We can access it if we turn towards it. What might this practice of turning look like? Prayer, mindfulness, meditation—and creative activity dedicated to this presence, because creative activity is what this presence is.

A Holy Nights practice

My continuing practice of creative activity takes different forms at different times. Recently, it led me to an exploration of virtue—what it is and how I experience different virtues and strive to cultivate them—and a painting practice to work with these questions.

To deepen my understanding, I did a small investigation of virtue in different traditions. The New Testament, Galatians (5:22-23), mentions love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. In the Old Testament, the Hebrew word chayil can be translated as “virtuous,” and is used to refer to strength, force, power, valor, and worthiness (Ruth 3:11, Proverbs 31:10). The ten commandments can be seen as the development of virtues (Exodus 20). In Aristotle’s Rhetoric, we read: “The forms of Virtue are justice, courage, temperance, magnificence, magnanimity, liberality, gentleness, prudence, wisdom.” (Rhetoric 1366b1.) A core set of values is heavily emphasized in Hindu tradition: Ahimsa (non-violence), mind and sense control, tolerance, hospitality, compassion, protection, and respect for all living beings and for the sanctity of all life. In Buddhism, we can see the virtues in the Noble Eightfold Path. The Sufi tradition speaks of the virtues of the Prophet of Islam, which encompass qualities like love and devotion to God, sincerity, compassion, humility, patience, discipline, and detachment. In several Bantu African cultures, the word Ubuntu (often translated as “I am because we are”) is a collection of values and practices that highlight virtues centered around interconnectedness and humaneness. All these traditions considered virtue to be significant for the development of the human being who is spiritually striving. Every spiritual path contains a stage of purification, a looking at oneself, and a striving to be a better person. It is only through a clear instrument that the spirit can be invited in.

In her book, The Secret Doctrine (1888), H.P. Blavatsky assigned 12 virtues to the 12 zodiac signs.1 When Rudolf Steiner was asked about this, he confirmed the relationships and added 12 more, one to each virtue, as an “enhancement.”2

Aries: Devotion becomes power of sacrifice

Taurus: Equilibrium becomes progress

Gemini: Perseverance becomes faithfulness

Cancer: Selflessness becomes catharsis

Leo: Compassion becomes freedom

Virgo: Courtesy becomes tactfulness of heart

Libra: Contentment becomes self-composure

Scorpio: Patience becomes insight

Sagittarius: Control of speech and thinking becomes a feeling for truth

Capricorn: Courage becomes power of redemption

Aquarius: Discretion becomes power of meditation

Pisces: Magnanimity becomes love

During an monthly online contemplation on each of these virtues, offered by author and meditation teacher Lisa Romero,3 I started working contemplatively with them. As I worked, I began to realize what strong medicine they hold.

Maintaining Balance

In Spiritual Foundations of Morality, Rudolf Steiner speaks about the polarities within which a virtue lives. “The pupils of the Mysteries were shown that freewill can only be developed if a person is in a position to go wrong in one of two directions; further, that life can only run its course truly and favorably when these two lines of opposition are considered as being like the two sides of a balance, of which first one side and then the other goes up and down. True balance only exists when the crossbeam is horizontal. They were shown that it is impossible to express man’s right procedure by saying: this is right and that is wrong. It is only possible to gain the true idea when the human being, standing in the center of the balance, can be swayed each moment of his life, now to one side, now to the other, but he himself holds the correct mean between the two. Let us take the virtues of which we have spoken: first—valor, bravery. In this respect human nature may diverge on one side to foolhardiness … Foolhardiness is one side; the opposite is cowardice. A person may turn the scale in either of these directions.”4

The virtue is found in a middle way, not as a synthesis of the two extremes. Although other people have named the specific polarities that surround each virtue, I felt it was important to determine this for myself. Before this work, I could flippantly think that yes, I was a compassionate, patient, or persevering person. But when I began to contemplate the polarities between which each virtue lives, I gained a new experience of my own shortcomings and therefore a clearer picture of what I needed to work on. I thought I was compassionate, but when I looked, I saw my own disinterest, on one hand, and my smothering concern, on the other. I thought I was patient, but then I noticed my impatience and also my lethargy. I began to work with seeing the two-sided opposites associated with each virtue. The polarities can be named in a variety of ways, but I always found them in myself, wherever I was too much, too loose, too superficial, on one side, and too little, too tight, too rigid, on the other—wherever I could lose myself in the world on one hand, and I could lose myself in myself on the other.

Painting Practice

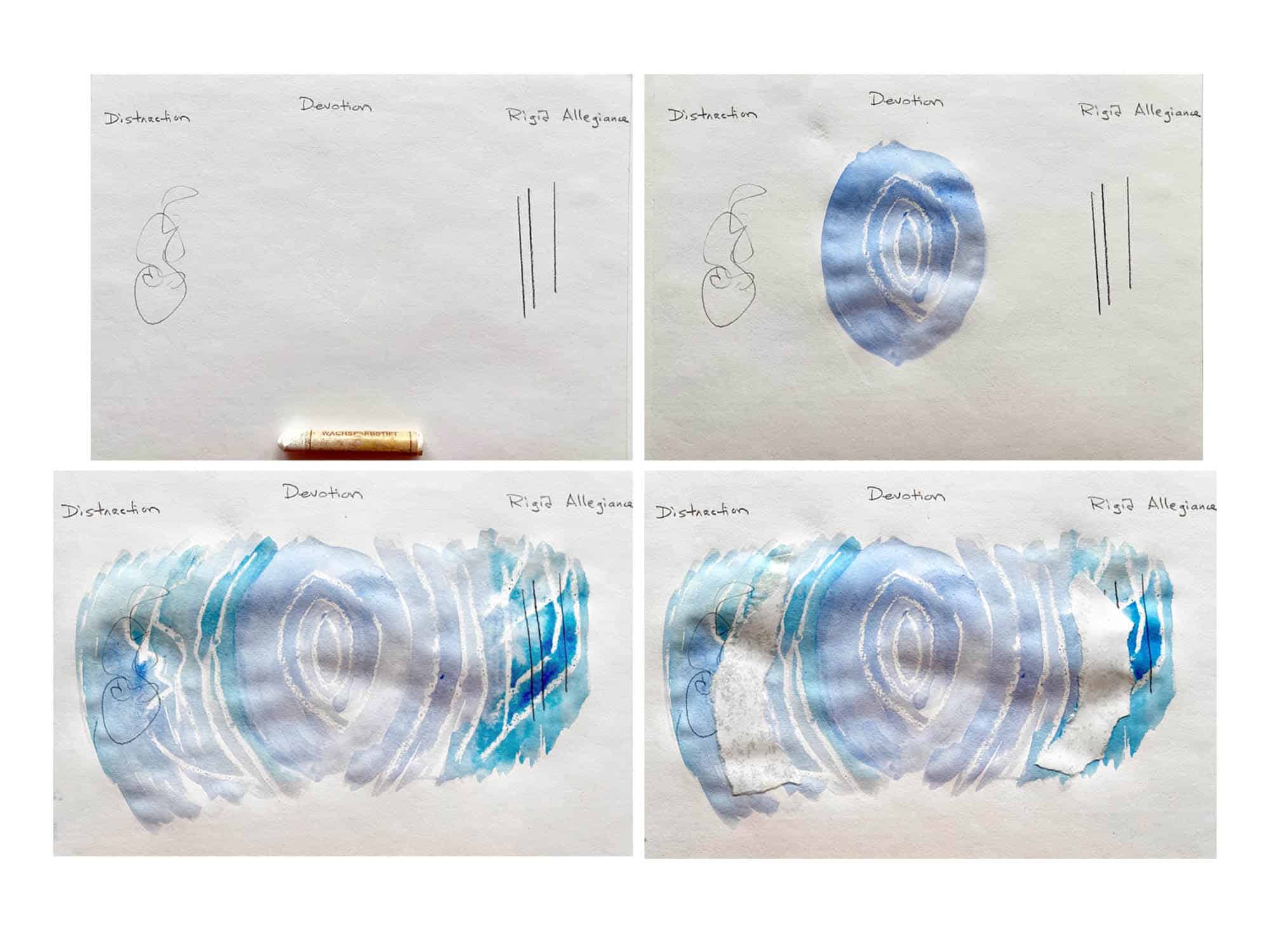

I am a painter, and I learn by painting. So, I created an exercise to see if, by painting the transformation between the polarities and the virtue, I could effect some change in myself. I worked with one virtue per day during the twelve Holy Nights, trying to experience the polarities within which the virtue found a center. To me, this center seemed like an activity of the Christ.

I started with the polarities, trying to feel the quality of the activity of each one. I made a scribble sketch for each polarity on opposite edges of the paper, and then a gesture in the middle for the virtue. Then, using a layering technique with water color and collaging paper, I transformed the whole painting first into the feeling of the virtue and finally into the expansion or enhancement of the virtue. As an example, distraction and rigid allegiance are considered the polarities of the virtue of devotion; the power of sacrifice is its enhancement. I asked myself: What does this virtue feel like? At what point do I move into the enhancement? How do both the virtue and the enhancement live in my painting?

I had a remarkable insight while reading Herbert Witzenmann’s contemplations of the virtues: “in reverence for the spirit in us and in all beings, we rise toward ethical individualism.”5 Developing the virtues is a way forward in our troubled and despairing world!

Each virtue has a slightly different quality, a different flavor. By observing my feeling realm, I could identify what is different and also what the feeling-quality in every one of these virtues is. As I worked, I became aware that the first set of virtues identified by Blavatsky were things that I could work on in myself, whereas the second set, added by Rudolf Steiner and often called “enhancements”, were an activity that could flow into me from the spirit, to the extent that I had worked on the first. I learned through this work to devote myself more strongly to the middle space. No matter your tradition or what you name this middle space, it has a strong presence.

More If you are interested in this work, contact Laura Summer: laurasummer@taconic.net.

Image Examples from Laura Summer’s painting practice

Footnotes

- H.P. Blavatsky, The Secret Doctrine. The Theosophical Publishing Company, Limited, London, 1888.

- Rudolf Steiner, Guidance in Esoteric Training. Forest Row, Rudolf Steiner Press, 2007.

- Lisa Romero, Astral Arc: Virtues.

- Rudolf Steiner, “The Spiritual Foundation of Morality” GA 155, May 30, 1912.

- H. Witzenmann, The Virtues – Contemplations, Folder Editions, NYC, 1975.