Are we at the dawn of a new golden age—one in which the promises of the Enlightenment are fulfilled, human hardship is overcome, and new freedoms take root—or are we witnessing the beginning of the end, a slow displacement of humanity and its culture? This was the question moderator Simone Miller posed to the thinkers Markus Gabriel and Daniel Kehlmann at the international philosophy festival phil.cologne in Cologne.

Markus Gabriel’s simple answer: “It’s entirely in our hands.” It depends on which artificial intelligence (AI) systems we build and, in particular, who builds them, because AI is not value-neutral like other technologies. Neural networks collect data—often human behavior expressed as data—form patterns from this data and reinforce these patterns. Therefore, the outcome depends on the data and on how patterns are formed. While it’s often said that technology changes human behavior, Gabriel reverses the argument for artificial intelligence: human behavior, condensed into data, shapes AI. He adds another thought: AI doesn’t just work for us, but with every query we give it, we provide data and thereby work for these neural networks. The answers AI supplies—the product we receive—come about only through the questions.

Daniel Kehlmann picked up on this contradiction, emphasizing that neither the users nor the developers of artificial intelligence know exactly why and how it is possible. What is important, he said, is that developers realized that it is less about improving the algorithms and more about increasing the amount of data and the speed at which it is processed. “Then the results don’t improve gradually but exponentially. No one knows exactly why this is the case.” He summed it up in a simple image: we have built a vast collection of data on the internet over the last 40 years, and artificial intelligence enables this entire data field to be used for answering our questions.

AI Makes Us Humans More Intelligent

Then moderator Simone Miller asked what AI actually is. Markus Gabriel’s answer: systems built to perform behaviors that are considered intelligent when performed by a human or other living being. They are “simulations of intelligent behavior.” He defined intelligence as the ability to solve a given problem in a finite amount of time. If artificial intelligence can be used to solve a problem more quickly, then our own intelligence increases. He offered an intriguing perspective: what’s interesting is not the intelligence of AI but rather the increase in human intelligence through the use of AI. Gabriel then asked whether the simulation of intelligent behavior is itself intelligent behavior. There are many examples of simulations that do not correspond to the original. Pointing at a Mediterranean beach on a map or on Google Maps isn’t relaxing.

The simulation of the trip is something completely different from the actual trip. Does this apply to AI? Gabriel suspects that the simulation of intellectual behavior is different in this case: “These things think.” Daniel Kehlmann described an experiment in which an AI model was asked to speak in Cornish. This language, which is related to Breton and Welsh, is spoken by only a few hundred people in Cornwall. So, there are hardly any Cornish texts on the internet—only a dictionary. Nevertheless, the AI model managed to express itself in Cornish. According to Kehlmann, this astonishing ability shows that AI cannot be derived from the data alone.

AI Has No Problems

But, asked Simone Miller, what about artificial intelligence compared to a more sophisticated concept of intelligence that includes, for example, adaptation to an environment and the ability to develop survival techniques? According to Gabriel, this is the “old line of AI philosophy,” and he quoted John Haugeland: “Computers don’t give a damn.” AI systems don’t care about anything. Intelligence is found everywhere in life and then grows gradually, from single-celled organisms to slime molds. All these forms of intelligence have the urge to survive in common. If intelligence is the ability to solve a problem, he asked, can one be intelligent if one cannot have a problem? But Gabriel didn’t want to follow this line of reasoning and asked whether the processing of thoughts itself was not thinking. Can thoughts think themselves? Asked Kehlmann and Gabriel, bringing up the positions of philosophers Gottlob Frege (1848–1925) and Georg W. Hegel (1770–1831)—that only living beings can think and that there is thinking in itself. Neither wanted to answer, but according to Gabriel, it’s looking good for Hegel. If thinking were indeed the processing of thoughts independent of “living embodied beings,” then artificial intelligence would become dangerous. But, interjected Miller, without a body, without sensory experience, no consciousness could arise, despite all the amazing data processing. Kehlmann pointed out that Google, the company, uses robots to generate experiences of corporeality and then, as with data, scales these experiences through simulation. Kehlmann asked whether it might be possible to teach the “embodied being-in-the-world” that is inseparable from our conception of consciousness to technical entities.

The conversation between Kehlmann and Gabriel moved into questions that were more open and uncertain than before the advent of this new technology. Perhaps this leads to an answer: AI calls us to determine our thinking, to determine ourselves, and to question the freedom of thought from the physical body. Perhaps body-free thinking will gain a place in machine-subconsciousness if it also occurs in humans. Kehlmann and Gabriel asked this too when they denied AI consciousness and did not want to make a final judgment. What a Socratic moment—something completely foreign to AI—to pause in the moment of not knowing.

Translation Laura Liska

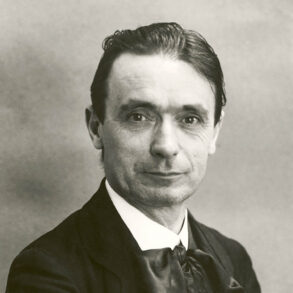

Image International Philosophy Festival phil.cologne on YouTube: “My Algorithm and Me”—Markus Gabriel and Daniel Kehlmann on humanity in the age of AI.

Does AI make humans more intelligent, or does it have the potential to do so? It can make humans more intelligent, yes, but is it a given that it does?