Every Autumn, the Goetheanum receives a new cohort of students for the three-trimester Anthroposophy Studies on Campus. Central to the learning experience are class trips to Chartres, Paris, Weimar, and Buchenwald, which expand and contextualize Steiner’s work, and address one of our main challenges today: to place anthroposophy in dialogue with the work of others, making it public and accessible to anyone who wishes to become acquainted with it.

The Anthroposophy Studies at the Goetheanum brings international and intergenerational students together with subjects and teachers from multiple disciplines. It is offered through a collaboration of the different Sections of the School for Spiritual Science at the Goetheanum, who work together to facilitate a contemporary, open approach to the study of Rudolf Steiner’s spiritual science.

From the start, participants and teachers step into a space that requires understanding each other and the course content step-by-step, building trust in learning together when differences abound. They encounter multiple languages, translations aplenty, different uses of the common language, English, and varied levels of experience with anthroposophy…

“We come together each weekday morning to study the book Theosophy—the same book in at least 15 different translations. This incredible diversity of language and reference material was a bit daunting, cumbersome, and even ridiculous at first; how can we all study one book when we all have different books? But after a little time, we came to see it as a metaphor for what we are studying. All of these differences, which could be viewed as discrepancies, can also be approached with openness and positivity. The challenge of using a common language [English] that is uncommon to most of us requires our attention to be very deliberately directed to understanding. Our teachers guide the thought, weaving of all these colorful threads into recognizable patterns that reveal the wisdom to us.” – Student testimony

What Does It Mean to Be Human?

The study of Steiner’s Theosophy during the Autumn trimester serves as an anchor and a point of orientation for shared learning of anthroposophy. A beginning takes shape, grounded in the question “What does it mean to be human?” Within this context, the students travel to Chartres in France, via Paris, and are introduced to Rudolf Steiner’s remarkable descriptions in his Karma Lectures in 1924 of the School of Chartres, Alanus ab Insulis, Bernardus Silvestrus, and Thomas of Aquinas, and his synthesis of faith and reason, and spiritual life and the natural world. Chartres Cathedral, with its magnificent architecture and spiritual heritage, becomes a space for observation and reflection, opening, through Steiner’s work, new perspectives on Western spirituality and its history. The students are introduced to earlier attempts at bridging reason and faith, cosmic order and natural form. Anthroposophy and the School of Spiritual Science are thereby placed in a stream of history as a developmental path of contemplative learning and study that reaches back to ancient mystery places, rooted in the wisdom of antiquity, yet gazing into the future.

In the Spring trimester, the students return to the roots of all of Steiner’s endeavors and travel to Weimar—a city central to German intellectual and cultural history. Here, they encounter Goethe, Schiller, and Nietzsche among others, not only as historical figures but as living dialogue partners in Steiner’s work and life. The trip contextualizes Steiner’s early philosophical writings (The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe’s Worldview, Philosophy of Freedom) and his engagement with epistemology, individualism, and ethics, which remain central to his later work and to us today. The students also deepen their understanding of Rudolf Steiner’s personal striving by looking at his active reception of these authors. His work in Weimar and what he developed there would eventually lead to his connection to the Theosophical Society and the founding of the Anthroposophical Society.

“The trip to Weimar was not a journey to a place, but a continuum. Space truly became time. A multitude of Inspirations arose. It was a living time, where hearing was enhanced. The intervals between time were brimming with possibilities.” – Student testimony

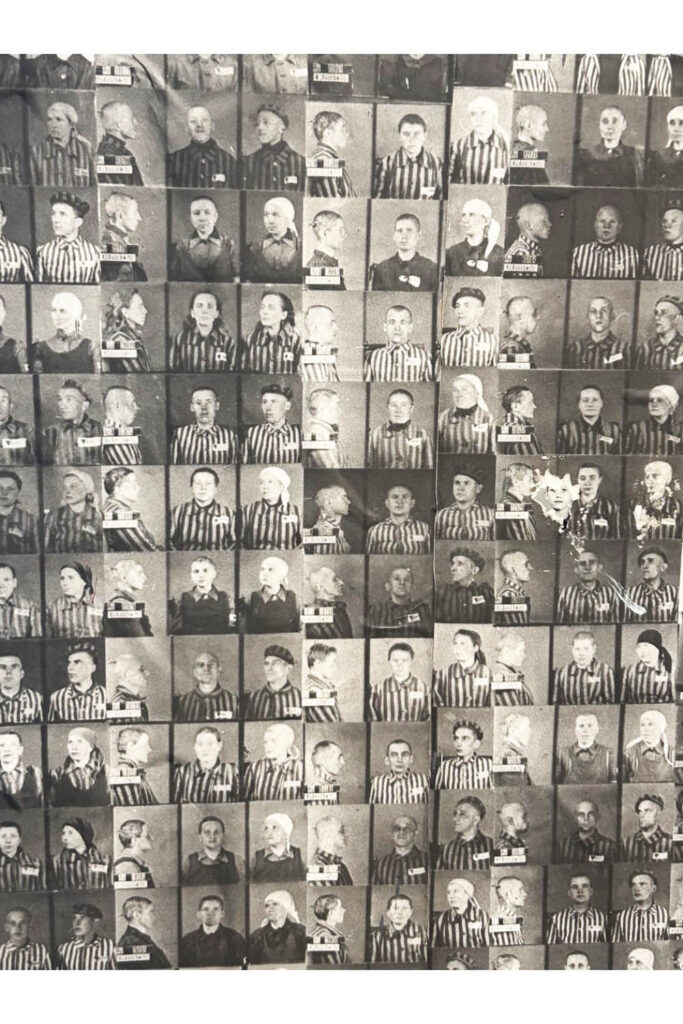

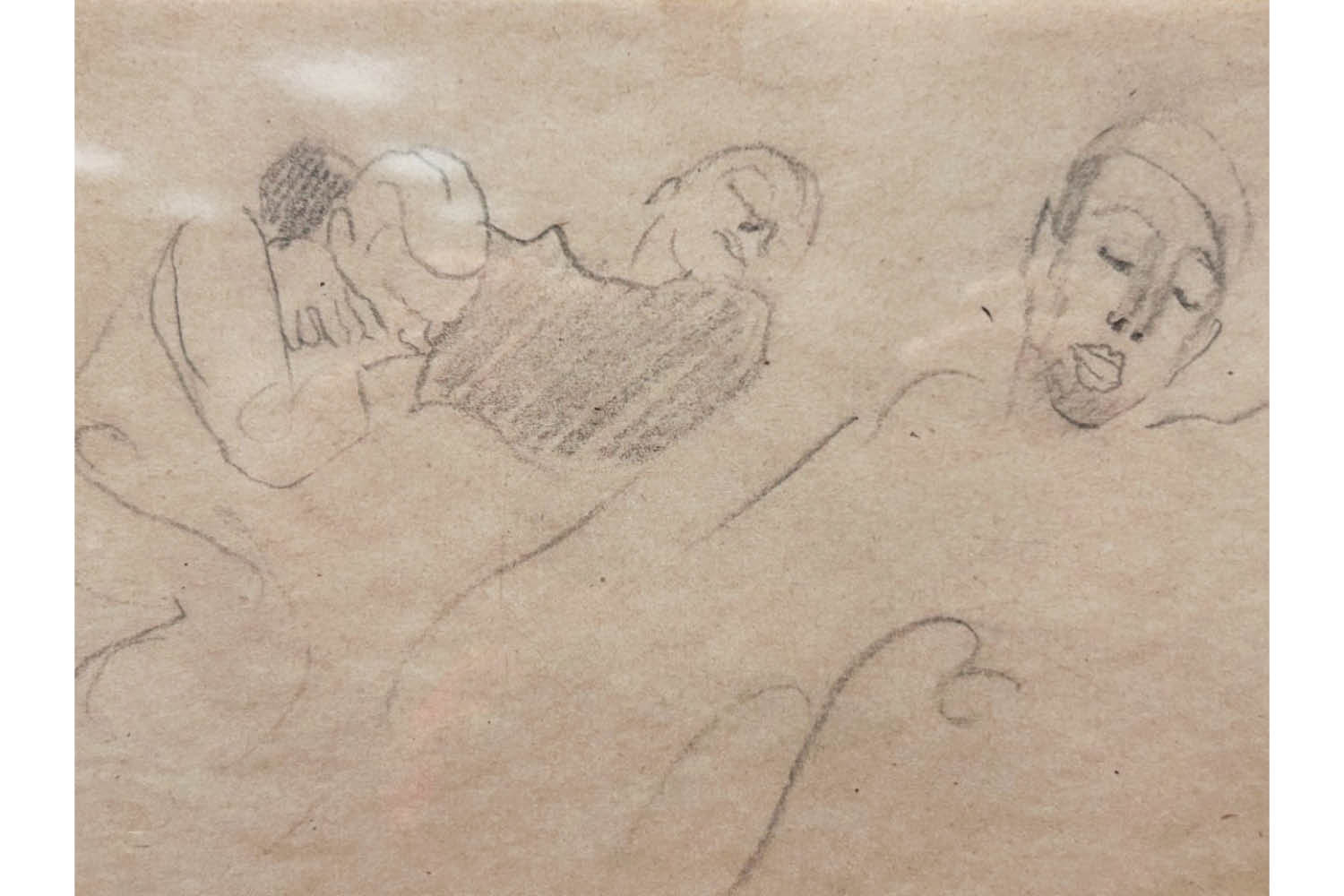

Left: Prisoners photos, exhibition Buchenwald Memorial Site; Right: Drawing by Paul Goyard, Buchenwald. Photos: Andrea De La Cruz

The second day of the trip is a visit to the Buchenwald Memorial Site, a few kilometers from Weimar. The site, with its preserved architecture, memorial gestures such as flowers and commemoration stones, an art and historical museum, and archival records, stands as a sobering counterpoint to the legacies they just explored in the city. It offers a space for reflection on the grounds and consequences of dehumanization.

Amid the shadows of the past, the students encounter powerful traces of human spirit and resistance in the exhibition “Means of Survival–Testimony–Artwork–Visual Memory.” It offers a stark contrast to the National Socialist obsession with record-keeping, cataloguing, and reducing human beings to numbers, files, and data. Paul Goyard’s pencil sketches include portraits of fellow inmates and glimpses of daily life, as well as the vulnerability of being alive, staying alive, and resisting. One senses the human forces reaching beyond the physical reality of the body, the pain, the earth, and the misery, to unite themselves with life, spirit… hope? His sketches are not forms of surveillance but invitations to witness—to see the prisoner as a human being, so full of potential and so immense as a spiritual being that we can only grasp their actual humanity as a sketch in becoming. The moment the human being is fixed—like in the records, the photographs, and the lists—he is no longer there. But in a few gentle, simple lines, we are invited to imagine this or that unique individual in a moment, just a moment, as an open question.

Amongst these artistic glimpses we find portraits, landscapes, still lifes, and images of fairy tales. The artworks are testimonies of the strength and nourishment that comes from imagination. Maybe they offered, as Tolkien once said, escape—not escapism—for recovery and reclaiming of soul forces under the most dehumanizing conditions. Fairy tales, images, imaginations, and art, far from fantasy, become ways of spiritual resilience. They open inner windows and doors to the human being. This echoes Goethe and Schiller’s understanding of art and the plasticity of the soul: the “play drive” as a way to sustain polarities and keep in movement—alive, even in the face of the abyss.

How Can I Think the World Anew?

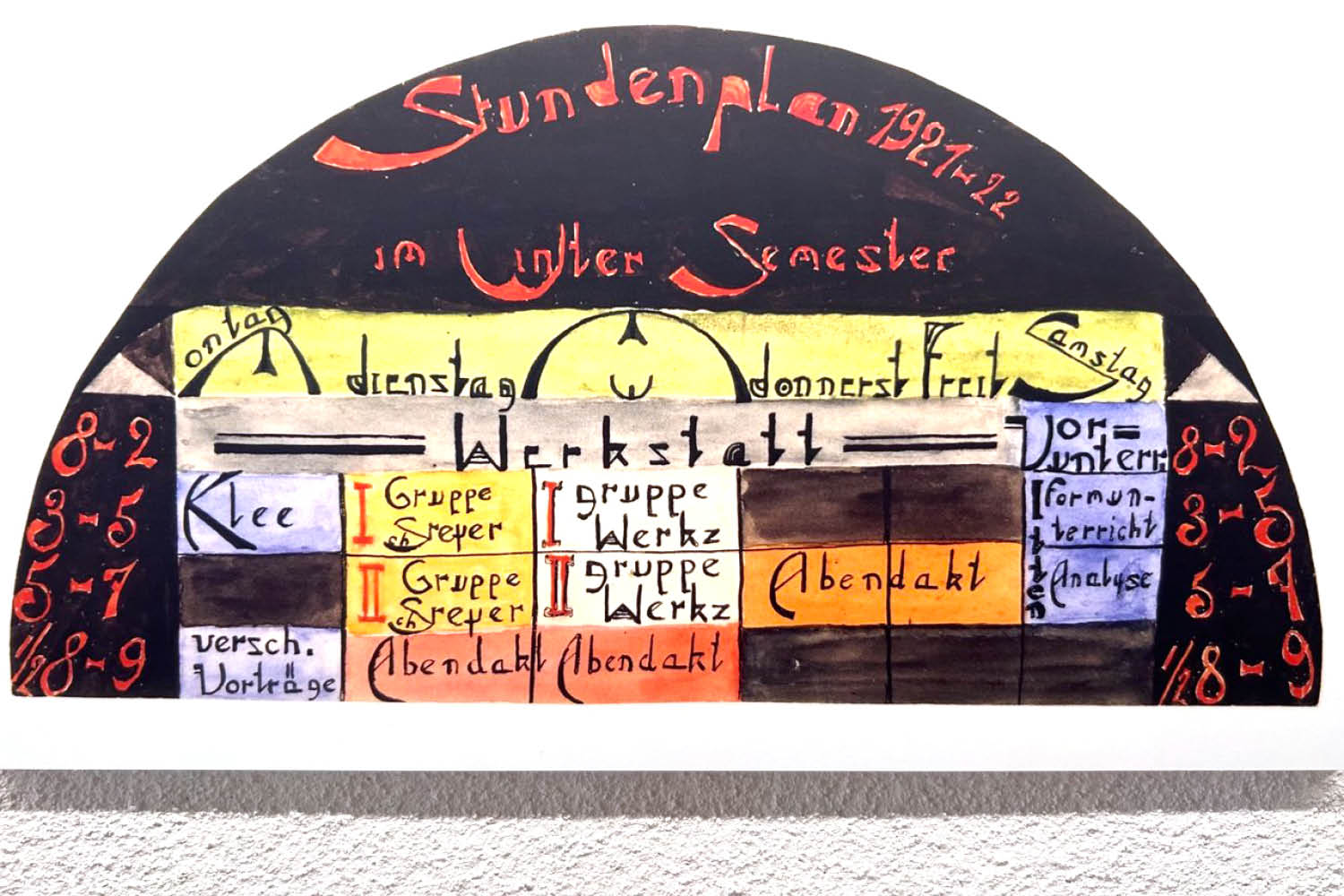

After returning to Weimar from Buchenwald, the work of Rudolf Steiner is given further context by exploring the works of artists, designers, and craftsmen of the Bauhaus (Henry van de Velde, Walter Gropius, Paul Klee, Kandinsky, and others). At the Bauhaus University and Museum, the students become acquainted with other early 20th-century attempts at founding new educational movements based on interdisciplinary research, praxis, and reflection on the role of the human being in relationship to the objects and landscapes that surround them in modern times.

Walter Gropius’ critique of his students’ first exhibition—“many pretty frames, splendid presentation, finished pictures”—captures that the focus is on process. What is sought is not perfection, but movement: a willingness to explore, to play, to search, to engage with others in seeking, and to learn from and with one another. Reminiscent of anthroposophy “as a path of knowledge” (as Steiner writes in the first Leading Thought) rather than a collection of ideas, results, or a system, it is a method that emphasizes the need for dialogue, encounter, trial, and play, as essential to being human.

The Bauhaus movement asked, “How can I think the world anew?”—a question that also lives in the School for Spiritual Science. In order to contribute new visions of the world, it seems important to contextualise and clarify the role of this Goetheanum School amongst other contemporary educational institutions: a free School of Spiritual Science for research and learning; a Goetheanum open to all, where art, study, contemplation and praxis come together in an attempt to build bridges, to reconcile; a school where imagination, living thinking, acts as a mediator between potential and destiny, like creativity mediates between the blank canvas and the creation.

Through the class trips, the students at the Goetheanum encounter the work of Rudolf Steiner more vividly and connect to the deeper meaning of education as an evolving, relational act. In the stained-glass windows or sculpted porches at Chartres, the works of Goethe and Schiller, Goyard’s sketches in Buchenwald, or the experimental and process-based spaces of the Bauhaus, we are invited to see the human being as an open question, and out of an understanding of this potential, to actively think and form the world anew.

The Anthroposophy Studies on Campus is one of the further education programs offered by the Goetheanum’s Studium and Further Education department. For information about all their programs, visit: Goetheanum Studium.

More Buchenwald Memorial, Bauhaus Museum Weimar

Title image Student excursion to Weimar. Photo: Goetheanum Studium