When sacred sites are given protected status and begin to build fences and charge admission, individual visitors lose their sense of responsibility. On the Calanais Standing Stones, Stonehenge, and the question of free access to sacred sites.

I remember a summer solstice at the Calanais Stone Circle (Isle of Lewis, Scotland) when there was also a full moon—a rare cosmic event. People flocked to the site; drums and singing filled the night—here a flute, there bagpipes, people in robes, druids, priestesses, and priests. At first, much of it was unfamiliar to me, but as I observed quietly, a peaceful, reverent atmosphere developed. Everyone celebrated their own relationship with the stones: some sought silence, others danced, and still others performed rituals. Different ways of connecting coexisted and complemented one another. At some point, I leaned against a stone and watched the goings-on. A couple I knew from previous visits joined me. They had just lost a child during pregnancy. The woman began to dance in the near dark of the midsummer night, and later we men joined in. Between the stones, we celebrated pain and grief in a small dance ceremony—it was meaningful and beautiful.

What I love so much about Calanais is that you can cross hills and meadows, from the water or from the moor, climb over a small stone wall—and you’re there. You can take a different path home—whatever your heart desires. This is how a relationship develops. And where relationships grow, responsibility also grows. So far, there hasn’t been any vandalism; people respect the stones—precisely because they’re freely accessible.

Admission Changes the Relationship

Now it’s been decided to fence off Calanais and to charge admission—£15 for a year-long pass. That in itself is not the problem. Of course, it’s reasonable to pay for people to maintain the site. The critical point is what almost inevitably goes hand in hand with this: restrictions. Admission is only worthwhile if the flow of visitors is channeled. So there will only be one entrance, and the rest will be fenced off, with security personnel and guards, as has long been the case at Stonehenge. And so, a question arises: what does this mean for our relationship with this temple in the landscape? Something freely accessible, that I can go to whenever and however I want, challenges me to take personal responsibility. When I have to ask to be admitted, purchase my right to enter, and then adhere to prescribed paths, times, and rules, the whole gesture changes. A free encounter now becomes a controlled visit.

Stonehenge: A Model—or a Warning?

I was at Stonehenge on the winter solstice. The solstices are the only times that the stones are openly accessible for a few hours—exceptionally, without an entrance fee. Many people from nature religions, Druidism, Wicca, and related traditions refer to Stonehenge as their temple; on these festive days, they’re granted access. On this night, we can actually walk up to the stones, touch them, and stand in the middle of the circle. Normally, we’re only allowed to walk on a wide circular path, at a distance from the circle, and only about halfway around it. We see the stones from a predetermined perspective. It’s often so crowded that it’s difficult to do more than take a few photos, like everyone else. There are various conceptions of how Calanais will be developed: tickets, fences, defined paths, limited times, and supervision.

As long as I can freely explore the countryside, I’m responsible for myself: not leaving any trash behind, not damaging anything, and respecting my own boundaries and those of the place. As soon as I pay an entrance fee, I expect trash cans, signs, clear rules, and supervisors who monitor everything. My inner “protect this place” becomes an outer “others protect it for me; I’m a customer.” It’s precisely when I hand over protection to others that my uncertainty grows. Can I trust these people? Do they have a real relationship with the place, or are they just managing it? The people who celebrate here throughout the year have a connection. They never decided to vandalize anything. The free model has worked thus far. With a fence and an entrance fee, something that was previously common property is privatized and taken away. What was once a living part of us—like a beloved friend—becomes a tourist attraction. A sacred place is transformed into a product, mainly used to photograph and show the world. “I was here, too.” The idea of being able to come back again and again with an annual ticket is well-intentioned. But, penned in like a zoo, part of a circus, the place loses exactly what makes it suitable for training one’s perception: peace, seclusion, and its own rhythm.

What’s at Stake

There’s a big difference between gentle intervention that reduces specific dangers and a system of fences, tickets, and controls. Calanais is not just about whether we’re willing to pay £15. It’s about whether we can continue to experience ourselves as people who freely, on our own responsibility, enter into a relationship with a sacred place—at any time of the day or night, on paths of our own choosing—or whether we increasingly outsource our relationship with the sacred to ready-made formats. What we risk losing is the possibility of an authentic experience of the sacred: that each and every one of us can visit this temple in the landscape in our own way, at our own pace, and on our own responsibility. A sacred place should simply be allowed to exist—open, without fences, without institutional protection. If it’s profaned, fenced in, and administered, then in its inward sense it’s no longer a temple—and thereby ultimately no longer truly protected.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

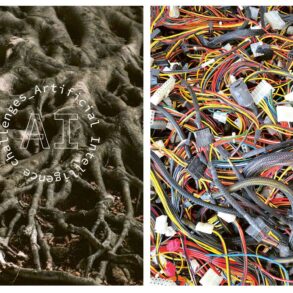

Image Calanais Stone. Photo: Renatus Derbidge.