Sexuality connects body and spirit in a unique way. But it is difficult to talk about it openly. Between digital omnipresence and spiritual repression, the intimacy and sanctity of this kind of encounter are being lost. A plea for an eroticism in which Eros, Philia, and Agape interact and encompass the whole person.

When we encounter two parents with a child bustling along the street, we instinctively know that at a completely different moment in their lives, the couple showed a transformed face: flushed, excited, desirous, bashful, beside themselves, perhaps also full of ambivalence, full of affection, infinitely tender, self-forgetful. We have all incarnated by way of two people sleeping together. Anyone who begins to read this text could not do so if a woman and a man had not had sex, had not made love. However, this act may also have been performed with one-sided pain and without agreement. (Artificial insemination is also not being considered here.)

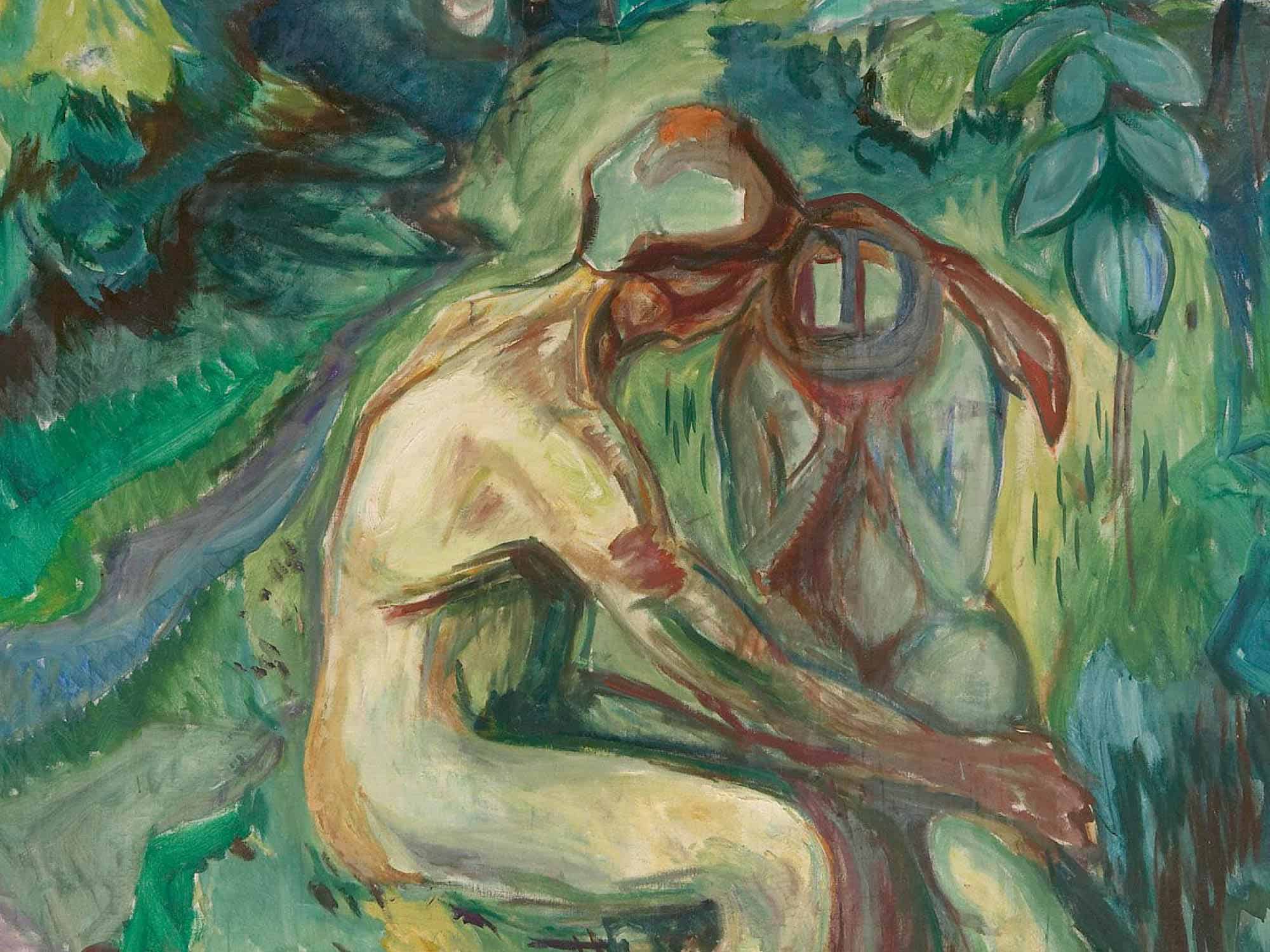

But we are also here in this world because two people have awakened together. Because sexuality cannot be realized without one becoming conscious of the other person with whom the experience is shared, one’s partner, in his or her very being. I make myself conscious of how beautiful their nature is, and I desire them. I want to become one with them in the moments of love that we are granted. Because, of course, we remain individuals, separate, and it is not uncommon for lovers to feel this way afterwards. Sometimes, however, the feeling of connection deepens, and desire is renewed. Those who love remain united and soulfully connected, preserving and transferring the experience of oneness from the physical act into everyday life. Whoever has united their lives with another human being wants to share it with them again and again. Not only sensual pleasure but also interest in the other person is constantly renewed, in what they think, how they feel and judge this and that, how they spent their day, and what they dream and plan. In the same way, the loving body is interested in every detail and every stirring of the other’s sensory form, in the tendon on the forearm, in the imperceptible typical movement, in the tiniest detail, in the hand and foot and skin and hair, because all is enveloped in an aura of reverence and closeness in which two people become children again: explorers and wonderers, full of play and trust. Free.

Sleeping Together, Awakening Together

But why is it so difficult to talk freely about sexuality? Is it because, if we are honest, it is also so difficult—so complex—to practice? Or because it is all too easy, at least in the public sphere, with all the support available everywhere, from toys to prostitution? Is that why we make it difficult for ourselves?

But really, it doesn’t help: what you don’t name is all the more present. Sexuality is omnipresent in the public media. The options for us to speak about it are not limited to talking about it or keeping it out of our conversation. This also applies to other needs. The convention that protects us is the convention that reveals what we’re doing. Whether I say, “I’ll be right back,” or “I need to quickly go to the bathroom,” everyone knows what happens there. The offensive, disarming, and frank handling of shameful aspects of existence is only possible if we as humans interact with each other in a socially loving way and are so naturally connected, so united in the relaxed knowledge of our equality, that nature does not push itself forward in the first place, but rather withdraws—and places itself entirely at the service of our linguistic, “technical,” and social joy of creation.

Sexuality is not an isolated field of interpersonal encounter but, rather, everything that we otherwise take to heart and agree upon in our coexistence crystallizes, condenses, and comes to a head in it. Today, we are sensitized, woke, and awakened to other people. But perhaps we also need to learn to sleep with each other again. In sleep, I trust. I stop problematizing. I let myself fall, I surrender myself, I close my eyes. That does not mean that we can be blind and close our eyes to the abyss of violence, abuse, false trust, and misunderstanding. But just as masculinity is more than poison, more than an overdose of dominance, just as femininity is more than passive hypersensitivity, and just as race may in the future only refer to the human race, so too is sexuality—or eroticism—more than just the act of intercourse.

Peripheries of Sexuality

When sex was liberated in the 1960s, it was captured at the same time and became, in the way it was lived out among people, a kind of program. And there have always been strange coalitions between spiritualistic teachers or guru cults and concepts of supposedly cosmic, free love. And yet, sexuality is not subject to ideology. It is something as intimate, sacred, and private as perhaps only death. It overtakes us; it makes us powerless. In death and in the discovery of my own sexuality, I am completely alone with myself, and just as suicide exists at the edges of the abyss, so self-gratification is one of the needs of sexuality. But today, digital possibilities tempt us to understand self-gratification more comprehensively as self-reflection, self-optimization, including self-transcendence and the overcoming of our mortality in transhumanism, so that young people in particular can hardly discover or discuss their sexuality independently of problematization. The pornography and violence available everywhere (rightly) evoke a pronounced morality as a reflex. Wanting to kiss someone seems to depend more on whether the other person has posted the same opinion about Trump on social media than on desire or sudden attraction. The “daemonic,” as Goethe called it, the overwhelming and inexplicable nature of love, the magic that is not necessarily evil, hardly ever appears.

What is actually quiet, suprasensible, mysterious, and in need of a protective space is being thrown into the collective: a safe space in a completely different sense, as a space for development for everyone, for the ‘I’, regardless of sex or gender.

Perhaps people reading these lines have never experienced sexuality, or never in a way that leaves them with fond memories and self-confidence. Or perhaps someone has not experienced it for a long time and carries a wistful feeling because their sexuality was tied to a specific person or a specific time. And there are people who have never been allowed to live out their form of love. Fortunately, deep tolerance is also part of the present day in the twenty-first century. Even the peripheries of sexuality are allowed to touch our hearts and live in our consciousness: the whole rainbow. The fact that the warmth of the heart’s blood supplies all and everyone, no matter what I choose, is like a gift from the spirit of the times.

But why is it still so difficult in some circles to talk and write about these things openly? Sexuality, including procreation and the ability to have children, is especially a source of fear of failure in society. But we meditate and sensitize our spirit and our soul not only for ourselves, but also for the world and for others. We ask one another: What do you need? What do you long for? When are you fully a human being? Completely the person you want to be, completely the desire you want to be, completely playing the role you are truly serious about? Or, in the words of the young, passionate Parzival, who stands on the threshold between the Middle Ages and the modern era: What confuses you, my friend, when it comes to sex?

Eros, Philia, and Agape

Do we, especially as explicitly spiritually striving individuals, sometimes underestimate each other’s generosity, serenity, and passion? Do we often fail to penetrate the world because we are not sufficiently imbued with “world”? In any case, spiritualization is not the opposite of embodiment, and sexuality is not the opposite of spirituality. They permeate each other. Only this experience makes love truly free, and lovers too. I do not want to be separated into a human being with whom one can talk so well and whose advice or interest is stimulating and attractive, and a physical body that does not attract one in this way. I want to be thought of as a physical body and as a spirit; as a human being, I do not want to be separated from myself, even though separation is omnipresent. Even if the other person “means no harm”: pity and eroticism are also mutually exclusive. Union means that the Greek words for love, the qualities of Eros, Philia, and Agape, work together: I desire to know and support you for your own sake, I desire to be your friend and always be devoted to you in my soul, no matter what happens. And because I feel all this, I also desire you sensorially. My love is a lemniscate: I feel all this, I feel your being, because I desire you sensorially. Your individual spirit permeates your form, your whole nature is present in your gaze and your hands. I cannot fix it to anything specific. It is this liveliness that determines my love, that ignites it, that grounds it.

If sexuality were a being, it might long to be truly liberated and connected with the whole human ‘I’: not oppressed by the moral, psychological, or corporeal, but supported by an ensouled, creative love-“making,” a love-filled speech that is open, honest, and therefore veiled. Sexuality is in danger of again becoming something we want to protect ourselves from, because it confronts us with something unattainable even within ourselves. Because it is not democratic. It does not treat us equally; it does not make us the same. It changes us. It is an expression of life’s deep love for us all.