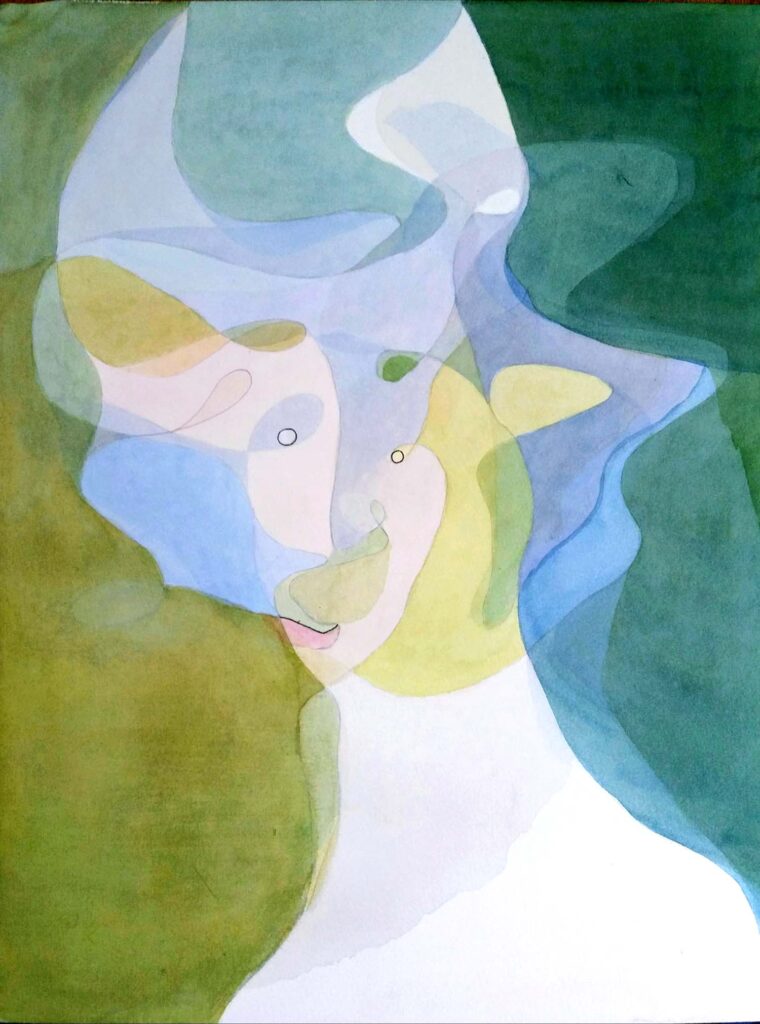

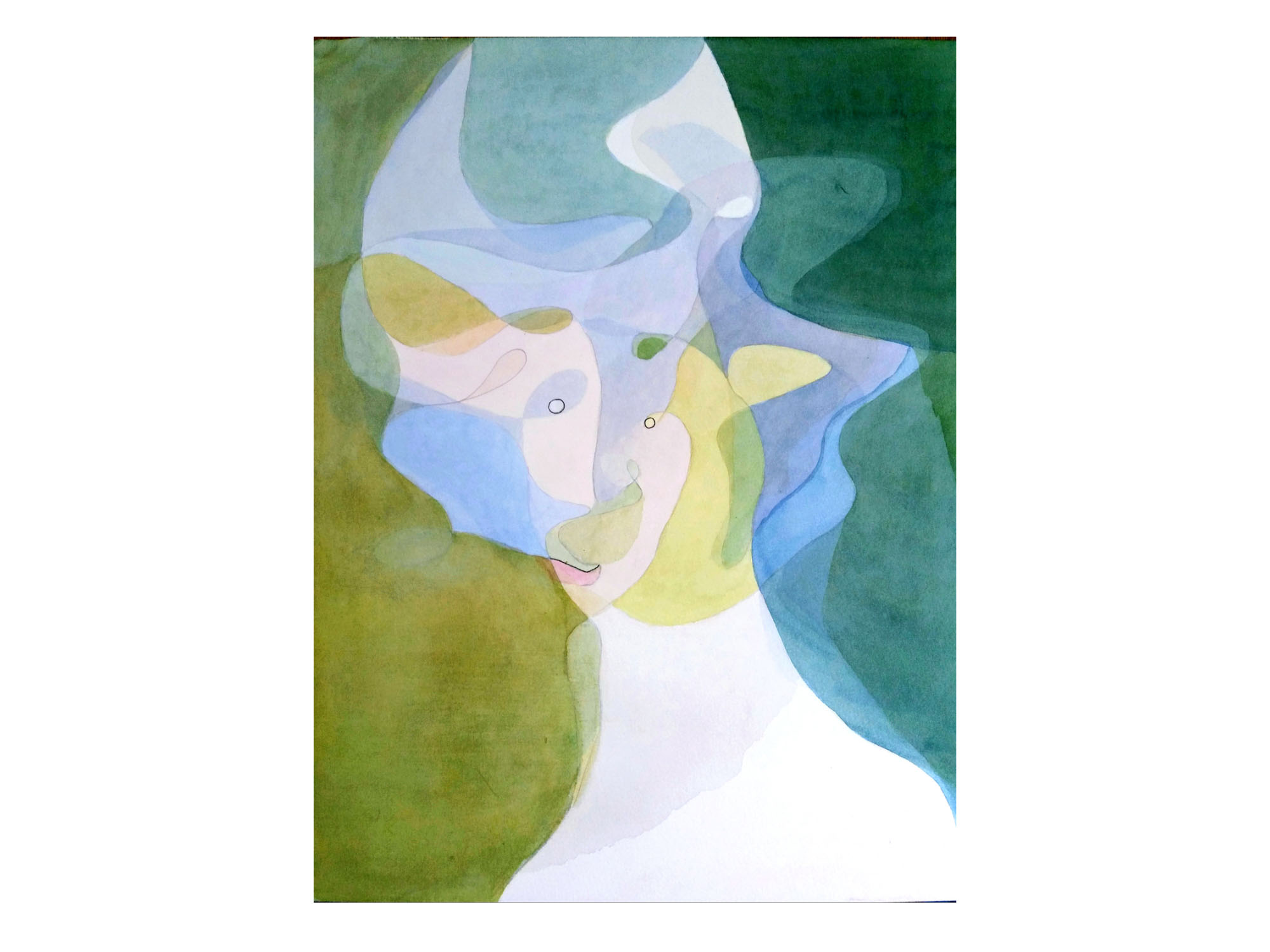

When perception and meaning appear to us as a unity in an image, we recognize them as landmarks or imaginations.

‹Imagination› is one of the more complex concepts of Anthroposophy, which is difficult to understand based on cultural and epistemological theory. On the cultural level, it is accompanied by a deep-seated fear of the image, which oscillates between early Christian iconoclasm and the modern will for abstraction. Simply put, this can be described as a deep distrust of the pictorial because it is not the object but its simulation, which appears untruthful and incapable of being real. For epistemology, the imagination is too deeply rooted in the subjective to lead to universal truth. The vision of celestial beings as winged humanoids seems to philosophers to be a fantasy collage of bird and human rather than a revelation of truth. If I want to penetrate these meanings with thinking, I have to clarify the terms ‹image› and ‹cognition›. The process of cognition can be understood in self-observation: both sensory perception and the observation of my soul activities, when perceived, occur without sense or meaning.

I face nature, another person, or a spiritual impulse and perceive them without knowing what they are. Only when I attach a thought to the perception do I begin to recognize a tree, my neighbor, or the feeling of joy. The more I think about it, the more thoughts and complementary perceptions I connect, the more I recognize, and the image of the idea of the perceived clarifies. In my bodily consciousness, I encounter perception and thought separately, although both originate in the same object. As a thinker, I bring together what I separate as a perceiver and thus create a complete picture of reality. I notice that the laws of nature, ideas, and thoughts are active in things. I realize that my sensory constitution breaks down reality into perception and thought.

In contrast to reality, the image is essentially two-part. In every image, whether painting, photo, idea, or imagination, I am dealing with a medium of appearance and what appears through it. For example, through the medium of oil paint, a landscape can appear on the canvas. The same applies to my ideas, based on which I can even perform an entire theatrical performance in the soul medium. In the pictorial, there are always two; that which wants to appear and a medium through which it appears. This distinguishes the image from reality, and thus the possibilities of the medium, its constitution, become decisive for the representation. What can be heard through a piano differs from what a cello can evoke.

Sensory and Spiritual Constitution

Through the medium of my sensory constitution, only those sides of reality are depicted which have no permanent, general character, which are therefore not thoughts, concepts, or truth, but only viewpoints. This relative, partial character can be shown in all sensory experiences: if I drink an espresso after eating something sweet, the bitterness becomes more bitter. The senses never show me how something is, but how something is in relation to my point of view and state. It is the task of thought to form a unity again from the fragmentary sensory world. Thinking is capable of letting the whole reality of what I perceive shine in my consciousness. However, it is initially chained to the sensory body, limited by the content perceptible to the the bodily. The fact that we can deduce the supersensible from the sensory traces leads us only to the border, but never to the promised land of the supersensible. But what would be a type of knowledge that is not dependent on the bodily constitution? Perception and thought will no longer occur separately. In this case, sensation and meaning will appear as one, perceiving and recognizing simultaneously. Spiritual science refers to this state of consciousness as ‹imagination› in the complete sense. But through what do I perceive, if not through the senses, if the body is not the medium in which the world is depicted? It is the task of the training to strengthen my consciousness so that it is maintained even without my nervous system, and the soul forms a sensory organ to the point of selflessness. When reached, the soul aspects change into my spiritual bodies, and the world suddenly begins to be reflected in them. In cooperation with the supersensible beings striving to appear, I then shape the medium of my soul so that thoughts and images become apparent to me as true images. Now I can form perception and meaning in their unity within me. I begin to have an imagination.

Unification of Perception and Thinking

The medium of appearance and my own soul are both a way and a risk. In an artistic work that depicts the world exclusively through favorite colors, everything is formed according to the respective sympathies, i.e. – they are less than fully true. But my soul itself is woven from my sympathies and antipathies and tends to color everything that appears in it. What then appears primarily is me through my soul, as a relationship to the world, and not the world in its reality. To serve the imaginative as a medium, the knowing person must not only transform their own soul but also know it in detail. Only in this way will no self-love spoil the truth. Because the soul is the most unstable aspect of my psychic being, true imaginative consciousness is not only difficult to reach but also full of error. It requires being extremely careful in the ‹seeing› of the imagination; any upset of the soul can easily lead to blindness and aberrations. We find an example in Rudolf Steiner’s fourth mystery drama: for a moment, in the pain of Strader’s death, the great initiate Benedictus fails to recognize Ahriman, who enters the room pictorially. Even at the highest stage of development, the soul, as a medium of imagination, can lead me astray. But if I am able to develop pure imagination, supersensible beings show themselves to me in soul images. They are, at the same time, an image and a revealed concept of truth. Here it becomes clear to me how Steiner could truly speak on such numerous, diverse subjects; at the source of imaginative consciousness as well as inspiration and intuition, the separation of perception and cognition is eliminated. What I see, I recognize with mathematical certainty. The difference between perception and thinking is eliminated, not because thinking stops, but because it is included. In the imagination, image and truth are one.

Translation Monika Werner

The words of your newsletter confirm the feelings in my heart.

Seeing your thoughts is a great step forwards. Watching your thoughts is an instruction most helpful.

This man has workedd hard and should be commended.the concept of pure thinking without a sensory referent and the following of Christ centred human ideals may help here.

There is always a danger of Kantianism and nominalism in the separation and recombining of sense based concepts, Steiner prefers the act of thinking as the joining of the external with the interior spiritual, with good reason, he wss developing Aquinian thought.And moral imagination is the practical application. Witness Nicodemus ( gospel of John) who as a pharisee insisted on a principle of judaic law that no person be condemned without a hearing and the opportunity to answer his accuser.The principle of natural justice found in the common law ( Kioa v West (1985)62 ALR 321, High Court of Australia), todayand no doubt in European law also!!

An abstract principle which to BE alive, must have practical application in every day life.THAT IS MORAL IMAGINATION!

We may also reconsider Kants critique of judgement and the concept of the sublime in aesthetics, reaching beyond the sensual..

In the beginning was the ‘word’ and the ‘word’ was made flesh.

observation, sensation, perception, conception require NO words or language of any kind. Only in the ‘absence’ of noise, intelligent or otherwise, can the mind practice contemplation, intuition and initiate counter-intuitive action! Only thus will humans become ‘Beings’ in his likeness.