Young Hamlet cries, “The time is out of joint: O cursed spite, that ever I was born to set it right!” He wants to set the times right, to take up his responsibility, and, with this step, he inwardly transforms from prince to king. This seems to be a symptom of our times: humanity as a whole is beginning to grow up.

Twenty years ago, at a conference of the Section for Mathematics and Astronomy, Wolfgang Schad gave a lecture on evolution. His main idea was that the path to Homo sapiens was not straightforward, but rather, it was a struggle for humanness, whether in terms of our upright posture or the shape of our head. One participant asked whether this project of “being human” was endangered by the ongoing destruction of the environment. The biologist and teacher then compared our situation as a society with that of an adolescent. At 16 or 17, many of us turn night into day; we eat very little that is actually good for us, and we consume tobacco, alcohol, and other harmful substances. The astral body bludgeons the youthful etheric body. The soul pushes life back—and, thereby, arrives at itself. Fortunately, young life is usually robust enough to survive this debauchery in the twenties until the time when yoga and jogging might take its place. According to Schad, part of the awakening of youth is that the soul subdues life in the organism. Today, this play of forces often escalates into a dance on a volcano. Schad continued, “In the 20th century, humanity as a whole was in a state of youth and pushed nature back, developing human consciousness at nature’s expense. But now, in the 21st century, we human beings have to take responsibility and grow up as humanity.”

The Bill on the Table

The climate crisis seems to be planet Earth calling out for our maturity. Species decline is animal and plant life calling out; the erosion of democracies is humanity itself calling out. According to a study broadcast by Austrian television, 67 of 137 countries surveyed were democracies, and 70 were autocracies. In light of these figures, the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk explained the democratic decline in a frighteningly simple way.1 It is not surprising, he said, because democracies can’t solve the principle of representation. A third of the population does not feel represented. This frustration “inevitably” leads to a shift to the right. According to Sloterdijk, the shift to the right describes the democratic deficit in a given system. CO2 emissions cause the global temperature to rise; a democratic deficit causes the fall of the global emotional temperature, compassion, and the ability to engage in dialog. Cause and effect intertwine, calling on us human beings to take responsibility—a sign of wanting to grow up, growing up, becoming an adult.

We Become Skeptical

Part of growing up is realizing that there are no simple solutions and that the world is not painted in black and white. From this perspective, the Cold War era seems like the youth of humanity. Back then, the world seemed so clear-cut. Here was the West; there was the East: two powers that each saw themselves as the salvation of humanity. This is how Ivan Krastev described it.2 According to the Bulgarian political scientist, communism in the East and capitalism in the West—both world views of the European Enlightenment—each saw in themselves the promise of making the whole world happy with their model of society. Despite all the nuclear threats and massive overkill at the time, it was an approach to life that promised a broad, bright future. What a youthful feeling!

The crises of the new century, with their gear-like interlocking, as Peter Sloterdijk described it, have turned this confidence into skepticism, and after the disenchantment at the beginning of the 20th century, they have again, and permanently, robbed us of the youthful certainty of a better time to come. “Every stage of life corresponds to a certain philosophy,” writes Goethe in Maxims and Reflections.3 He continues: “A child appears as a realist; for it is as certain of the existence of pears and apples as it is of its own being. A young person, caught up in the storm of their inner passions, has to pay attention to themselves, look and feel ahead—they are transformed into an idealist. A grown individual, on the other hand, has every reason to be a sceptic: they are well advised to doubt whether the means they have chosen to achieve their purpose can really be right.”

The whole of humanity now seems to have reached a skeptical state—it is, indeed, growing up. In the 20th century, the public, and, yes, perhaps even the World Spirit, was still tolerant whenever Europe spoke of values in the realm of politics while secretly representing and asserting its own interests. Today, this is happening openly around the world. Brazil or India may disapprove of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, but what counts politically are the interests, the answer to the question, “How do I maintain my influence, and how do I expand it in a complex, multipolar world?”

Everybody on Board

Four years ago, the headline in The Atlantic was “Why Greta Thunberg Makes Adults Uncomfortable.” Indeed, just as Astrid Lindgren’s Pippi Longstocking called out to us to become children again, Greta Thunberg and a generation along with her shouted, “Grow up!” “Grow up” is probably also the message of the African states that are now throwing off the last shackles of colonialism. What in each human being is a process of individualization now manifests itself in global politics as decolonization and a search for identity. The conflict in Palestine shows the narrative of decolonization through a magnifying glass. This is probably why it is making such waves worldwide. Growing up is a global pain; there is no higher authority, no ideology, no promise of salvation—we, ourselves, are it. Skepticism and interest-driven actions are the shadows of adolescence; responsibility, awareness, and the will to take all human beings on board, all together, are the light. To notice and promote this light in each and every other person is the virtue of our time.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

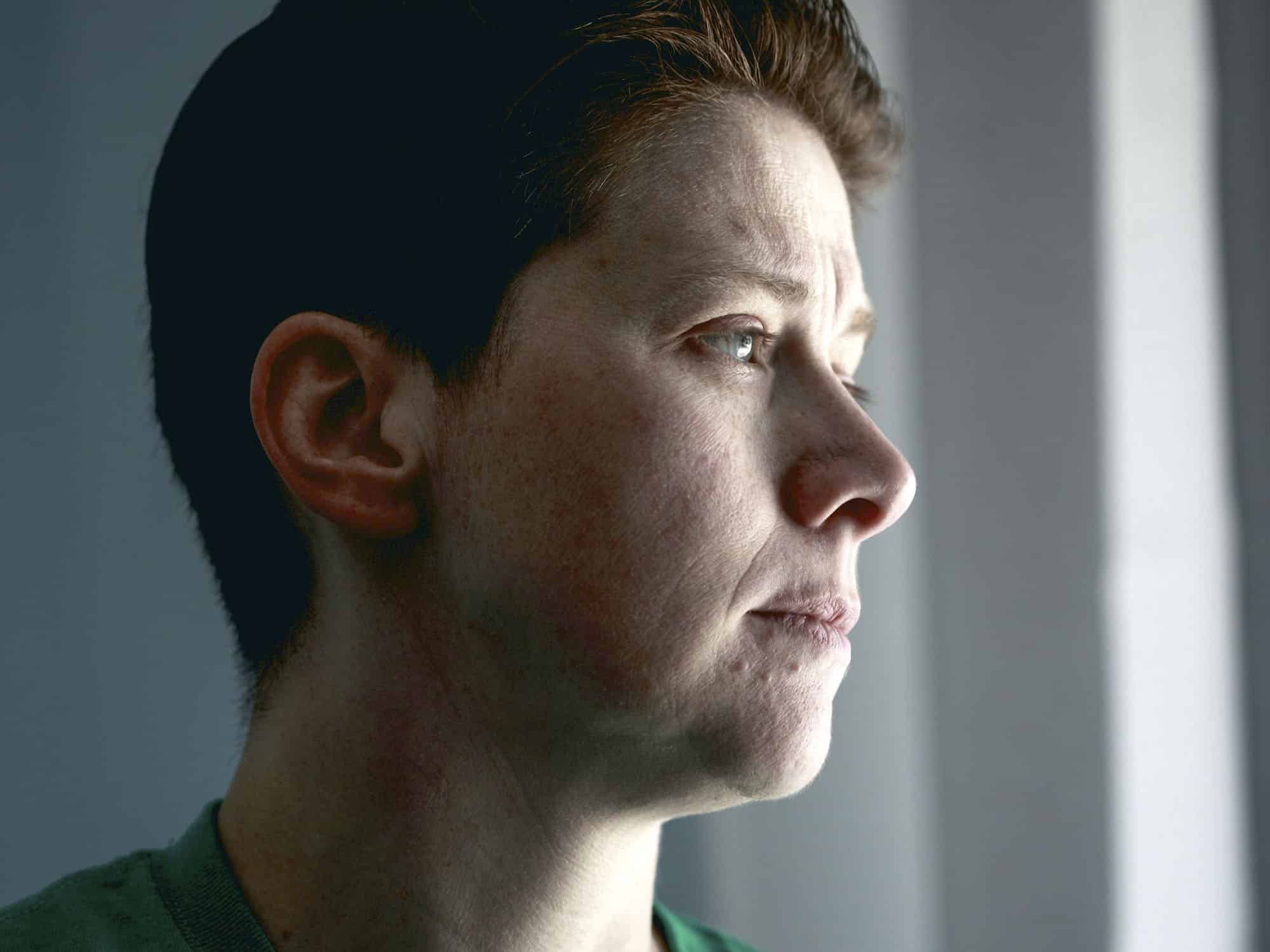

Photo Alexander Grey, unsplash

Footnotes

- Conversation with Imogena Doderer “Der Mensch als Brandstifter” [The Human being as arsonist], ORF 2 [Austrian public television channel], Kulturredaktion [Culture editorial office].

- Ivan Krastev interview with David Precht: “Zerrissene Welt: Zwischen Werten und Interessen” [A world torn apart: between values and interests] ZDFheute [German public television show].

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Maxims and Reflections, translated from the German by Elisabeth Stopp (New York: Penguin, 1998), maxim no. 806.