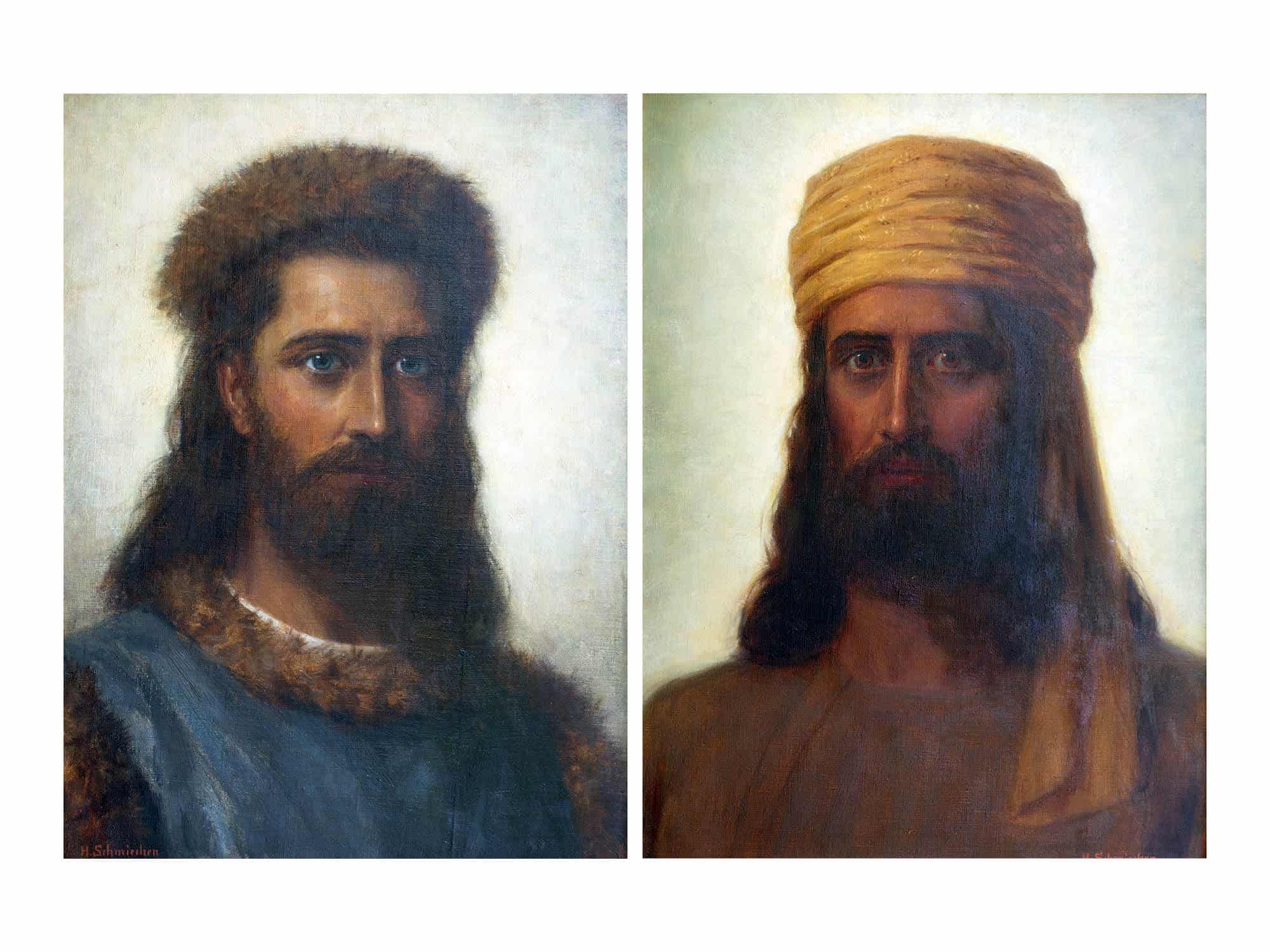

Copies of the Paintings of the Masters, often mentioned within the Theosophical Society, can be found today in the Rudolf Steiner Archive in Dornach, Switzerland. They were also important to Steiner. After the Anthroposophical and Theosophical Societies separated, the painter of the portraits committed himself to anthroposophy and remained loyal to Steiner.

Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), founder of the Theosophical Society together with Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, shares many astonishing events that he experienced as president of this Society in his Old Diary Leaves. One of these events is the creation of the so-called Portraits of the Masters or Mahatmas.1 Olcott had long wanted an image of his spiritual teacher Kuthumi (Koot Hoomi) and finally asked Blavatsky to obtain one for him, which she promised to do. First, a French artist friend, Monsieur Harrisse, made a pastel drawing by means of thought transmission. However, Olcott felt that it lacked “radiance of soul,” so he asked five friends—three of them painters—to create a better image based on Harrisse’s profile portrait.2 The German portrait painter Hermann Schmiechen succeeded in doing so. Between June 19 (one day before he became a member of the Theosophical Society) and July 9, 1884, he painted the portrait of Master Kuthumi and also that of Master Morya—the two “Masters of the East.” Olcott reports:

[Schmiechen] gave the face in full front view, and poured into the eyes such a flood of life and sense of the indwelling soul as to fairly startle the spectator. It was as clear a work of genius and proof of the fact of thought-transference as I can imagine. In the picture he has got all—the face, complexion, size, shape and expression of eyes, natural pose of head, shining aura, and majestic character. It hangs in the Picture Annexe of the Adyar Library that I had built for it with the companion portrait which Schmiechen painted of our other chief Guru, and on entering the room the visitor feels as if those grand eyes were searching their very heart. I have noticed the signs of this first impression in nearly every case, and the feeling of awe is enhanced by the way in which the two pairs of eyes follow one about the room, still seemingly reading one, no matter where one may stand. Then, again, by some trick of the artist’s brush, the shining aura about the two heads seems to be actually in a shimmery motion, just as it is in nature. No wonder the religiously-minded visitor finds themself, as it were, impressed with a sense of the holiness of the room where the two portraits hang, and meditative introspection is easier there than elsewhere. Grand as they are by day, the pictures are even more striking by night, when properly lighted, and the figures seem as if ready to step out of their frames and approach one. The artist has made two or more copies of the portraits, but they lack the life-like character of the original; he evidently lacking the stress of inspiration under which the latter were produced.3

The Origin of the Portraits of the Masters

Laura Holloway (1848–1930), a young woman who, as she herself recounts, was taken to the meeting by Blavatsky at the written request of the Master,4 describes in detail how she experienced what was probably the first painting session at Schmiechen’s:

And, at the appointed time, a number of Theosophists gathered at his studio. Chief among Mr. Schmiechen’s guests at that first sitting was H. P. B. who occupied a seat facing a platform on which was his easel. Near him on the platform sat several persons, all of them women, with one exception. About the room were grouped a number of well-known people, all equally interested in the attempt to be made by Mr. Schmiechen. The most clearly defined memory of that gathering, always in the mind of the writer, is the picture of Madame Blavatsky placidly smoking cigarettes in her easy chair and two women on the platform who were smoking also.5

Blavatsky had also asked Holloway, a non-smoker, to light a cigarette. Holloway recounts:

Strange to relate that though the amateur smoker considered herself an onlooker it was her voice which uttered the word “begin,” and the artist quickly began outlining a head. Soon the eyes of everyone present were upon him as he worked with extreme rapidity. While quiet reigned in the studio and all were eagerly interested in Mr. Schmiechen’s work, the amateur smoker on the platform saw the figure of a man outline itself beside the easel and, while the artist with head bent over his work continued his outlining, it stood by him without a sign or motion. She leaned over to her friend and whispered: “It is the Master K. H.; he is being sketched. He is standing near Mr. Schmiechen.”

“Describe his looks and dress,” called out H. P. B. And while those in the room were wondering over Madame Blavatsky’s exclamation, the woman addressed said: “He is about Mohini’s6 height; slight of build; wonderful face full of light and animation; flowing curly black hair, over which is worn a soft cap. He is a symphony in greys and blues. His dress is that of a Hindu—though it is far finer and richer than any I have ever seen before—and there is fur trimming about his costume. It is his picture that is being made, and he himself is guiding the work.”

Mohini, whom all present regarded with love and respect as the gifted disciple of the revered Masters, had been walking slowly to and fro with his hands behind him, and seemed absorbed in thought.

Holloway reports that she followed Mohini’s movements with attentive glances, as she noticed “a similarity of form between the psychic figure of the Master and himself, and, as well, a striking resemblance in their manner”:

“How like the Master Mohini is,” she confided to her friend beside her; and, looking toward him she saw him watching her with an expression of much concern on his face. Smiling back an assurance to him that she would make no further revelations, she glanced toward the artist and caught the eyes of the Master, who stood beside him. The look was one she never forgot, for it conveyed to her mind the conviction that her discovery was a genuine fact, and henceforth she felt justified in believing the Mahatma K. H. and Mohini the chela, were more closely related than she had before realized. In fact, that Mohini was nearer the Master than all others in the room, not even excepting H. P. B. And, no sooner was this conviction born in her mind than she encountered a swift glance of recognition from the shadow form beside the easel, the first and only one he gave to anyone during the long sitting. H. P. B.’s heavy voice arose to admonish the artist, one of her remarks remaining distinctly in memory. It was this: “Be careful, Schmiechen: do not make the face too round; lengthen the outline, and take note of the long distance between the nose and the ears.” She sat where she could not see the easel, nor know what was on it. . . .

How many of the number of those in the studio on that first occasion recognized the Master’s presence was not known. There were psychics in the room, several of them, and the artist, Mr. Schmiechen, was a psychic, or he could not have worked out so successfully the picture that was outlined by him on that eventful day.

The painting of the portrait of the Master “M” followed the completion of the picture; both were approved by H. P. B., and the two paintings became celebrated among Theosophists the world over.

In 1891, the lawyer Clemens Driessen (1857–1941), a friend and executor of Wilhelm Hübbe-Schleiden and a student of Rudolf Steiner, noted that he had encountered Schmiechen at the home of the Christian mystic Alois Mailänder with one of the master portraits: “Mahatma picture. M. [in] m[y] o[pinion] an ideal head without any particular significance. The very bright background creates a fascinating effect; Gabele speaks of a radiance that is well rendered and actually perceptible in highly developed individuals.”7

Who Was Hermann Schmiechen?

Hermann Schmiechen (Neumarkt/Silesia, July 22, 1855 to October 8, 1923, Berlin) initially studied painting in Breslau [today, Wrocław] in 1872 and then in Düsseldorf from 1873. In 1876, he went to Paris to study at the Académie Julian. He returned to Düsseldorf and soon became a sought-after portrait painter. Recommended by his colleague August Becker, he was appointed by Queen Victoria to Kensington Palace in London in 1883 to paint portraits of her family and other English aristocrats. Shortly before moving to England, Schmiechen married Antonia Gebhard, from the Gebhard family of industrialists in Elberfeld mentioned above, who were closely associated with the Theosophical Society from early on. The Gebhards temporarily hosted Helena Petrovna Blavatsky during her stay in Germany. Hermann Schmiechen painted portraits of Blavatsky in London and Elberfeld in 1884.

At the end of 1898, the couple divorced.8 Schmiechen returned to Germany and lived in Berlin-Charlottenburg from 1901 onwards.9 There he maintained contact with Rudolf Steiner and often asked his “esteemed friend” to visit him, which apparently took place. In 1908, he made copies of the “Mahatma pictures” in oil for Rudolf Steiner, which are still present in the Rudolf Steiner Archive in Dornach today. He wrote about this on December 21:

My dear, most honored Herr Doctor! Ms. v. Sievers brought me the fee for the one Mahatma picture on Saturday afternoon; the second Mahatma picture is a gift from me to you, as are the two frames for the pictures. Now I would like to ask you to confirm that you will lend me the pictures at any time should I need them for copying. I told Ms. v. Sivers this before I handed her the pictures, and since we are good, loyal friends, there will never be any difficulties between us in this matter. Isn’t that true? When would you be able to spend a leisurely evening or a few hours with me? I would like to discuss a number of questions with you. With heartfelt regards, your especially grateful and reverent Hermann Schmiechen.

After separating from the Theosophical Society, he informed Rudolf Steiner on April 10, 1913: “I just wanted to let you know that, as a good friend, I will of course remain loyal to you. Hopefully we will really be able to meet again soon.” So, the painter who had painted the famous Portraits of the Masters for and with Blavatsky, who had been a member of the Theosophical Society for almost thirty years, remained loyal to Rudolf Steiner! Apparently, Steiner and the Executive Board of the Anthroposophical Society were so moved by this that they awarded him honorary membership. This is evident from Schmiechen’s letter of November 7, 1913:10

My most dearly revered Herr Doctor! I would like to express my most intimate gratitude to you and Ms. von Sivers for designating me an honorary member of the Anthroposophical Society. I fully appreciate this honor and distinction and thank you once again from the bottom of my heart. Your especially reverent friend and brother, Hermann Schmiechen.11

In the years that followed, the painter endured several illnesses and became increasingly hard of hearing, so that he was no longer able to attend Rudolf Steiner’s lectures. In addition, a nerve disorder in his head hindered him in his painting. However, he wrote on March 9, 1922: “I have almost completed a picture of ‘Christ . . . with the apostles on the way to Jerusalem.’ I gave the apostle Nathanael your features.” He also recommended his work Das Kind der Wahrheit [The child of truth], a “prophetic work” intended to show “that truth is being reborn, and that Europe and Germany are the place where the child stands, from whence truth proceeds.” But apparently, the pictures, reproduced as a copperplate print, did not sell well among anthroposophists. Schmiechen’s painting style was probably no longer in keeping with the tastes of the time.

The painter died on October 8, 1923, in Berlin. He remembered Rudolf Steiner in his will, but his family claimed that he had been too optimistic in estimating his assets and that his will was therefore invalid. Hermann Schmiechen is largely forgotten as a painter today. Only his two “Master pictures,” which were reverently preserved in the circles of the Theosophical and probably also Anthroposophical Society—often in specially made protective cases—remain popular today.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Title image Master images (Kuthumi and Morya) by Hermann Schmiechen. Here are replicas made between 1906 and 1908. Rudolf Steiner Archive.

Footnotes

- Mahatma actually means “great soul,” a concept used to describe spiritually advanced human beings; in German, the term Meister is used for this; in English, Master. In his lecture of December 23, 1904, Rudolf Steiner said, “The Masters are not usually historical personalities; they sometimes incarnate themselves in historical personalities when it is necessary; but to a certain degree it is a sacrifice. The level of their consciousness is no longer consistent with working for themselves. And working for oneself includes the preservation of one’s name.” Rudolf Steiner, The Temple Legend. Freemasonry and Related Occult Movements: From the Contents of the Esoteric School, CW 93 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2000). There are also some statements by Rudolf Steiner about Morya and Kuthumi, whom he refers to as the two Eastern Masters; see Kosmos und menschliche Evolution. Farbenlehre [Cosmic and human evolution. Color theory], GA 91 (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2018), p. 109; as well as “From the Teachings about the Masters of Wisdom and of the Harmony of Sensations and Feelings,” in From the History and Contents of the First Section of the Esoteric School: Letters, Documents, and Lectures: 1904–1914 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2010). In the early esoteric lessons, Rudolf Steiner occasionally mentions the Eastern Masters, see Esoteric Lessons 1904–1909: From the Esoteric School, CW 266/1 (Great Barrington, MA: SteinerBooks, 2007).

- One of them was Isabelle de Steiger (1836–1927), a member of the TS since 1878 and of the Golden Dawn, later of the Anthroposophical Society in Great Britain. After the Goetheanum burned down, she wrote a letter to Rudolf Steiner expressing her sympathy.

- Henry Steel Olcott, Old Diary Leaves: The Only Authentic History of the Theosophical Society, vol. 3, 1883–1887 (London: The Theosophical Publishing Society, 1904), p. 156 f; on the subject of portraits of the Masters, see also the very informative outline: Massimo Introvigne, “Painting the Masters: The Mystery of Hermann Schmiechen” (Turin, Italy: n. pub., n.d.).

- “Take her with you to Schmiechen and tell her to see. Yes, she is good and pure and chela-like; only terribly flabby in kindness of heart. Say to Schmiechen that he will be helped. I myself will guide his hands with brush for K.’s portrait.—From K. H.” L. C. L. (Laura Holloway), “The Mahatmas and Their Instruments,” The Word 15, no. 2 and 4 (May and July 1912): 69–76, 200–206 (quote from p. 203).

- Ibid., p. 204. Schmiechen had also made copies of the original paintings of the Masters sent to Adyar for the Gebhard family, in whose house the Germania Theosophical Society, the first branch of the Theosophical Society in Germany, had been founded in 1884. The Swedish Countess Constance Wachtmeister writes about these copies:

These duplicates were given to Madame Mary Gebhard. The copies were so much like the originals that it was often disputed which were which. Only H. P. B., Olcott, and Mr. Schmiechen were never in doubt; and in order to stop these doubts one evening H. P. B. said: “Just wait, now leave those pictures alone!” at the same time evidently concentrating all her powers on them. Not many seconds afterwards she said: “Now turn them round.” We did so, and found on the back of each portrait the well-known corresponding signatures of the Masters, one in blue, the other in red.

Source: Constance Wachtmeister, Reminiscences of H. P. B. and The Secret Doctrine (London: Theosophical Publishing Society, 1893), p. 111.

- Mohini Mohun Chatterji (1858–1936), Bengali lawyer and scholar, member of the Theosophical Society from 1882 to 1887, private secretary to Olcott for a time.

- Quoted in Wilhelm Hübbe-Schleiden, Indisches Tagebuch [[Indian Diary] 1894/1896 (Göttingen: Norbert Klatt, 2009), p. 17. Hermann Schmiechen was also a student of Alois Mailänder for a time and went by the name “Jeremias.” Nikolaus Gabele was Mailänder’s closest friend and brother-in-law. For more details, see Martina Maria Sam, “Der ‘Bund der Verheissung’ um Alois Mailänder und seine Bedeutung für die frühe theosophische Bewegung in Deutschland” [The “Union of Promise” around Alois Mailänder and its significance for the early theosophical movement in Germany], Archivmagazin. Beiträge aus dem Rudolf Steiner Archiv [Archive Magazine: Contributions from the Rudolf Steiner Archive], no. 11 (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2021).

- The couple had four children—Herbert, Elsa, Wilfried, and Gerald Schmiechen—some of whom were raised in Darmstadt.

- In 1909, he was commissioned to paint a portrait of Emperor Wilhelm II.

- Letters from Rudolf Steiner to Hermann Schmiechen in Rudolf Steiner Archiv, Dornach.

- In his lecture on March 28, 1916, Rudolf Steiner even addresses him directly:

In 1909 in Budapest, I had something very specific to say to Mrs. Besant, which was as follows. It was in 1909, when Mrs. Besant began all sorts of nonsense—at that time, they wanted to make a compromise with me, because the intention was to appoint this Alcyone as the bearer of Christ. Well, isn’t it true that they wanted to make a compromise with me?—I believe it will be especially interesting for you, who have experienced such things, when I tell you about them, my dear Mr. Schmiechen.—They wanted to make a compromise with me, they wanted to appoint me as the reincarnated John the Evangelist, and then they would have recognized me as such. That would have become dogma there if I had gone along with all these various deceptions.

Source: Rudolf Steiner, Gegenwärtiges und Vergangenes im Menschengeiste [The present and the past in the human spirit], GA 167, 3rd edn (Basel: Rudolf Steiner Verlag, 2023), p. 88; omitted in all previous German editions and thus not present in the English translations, The Human Spirit: Past and Present. Occult Fraternities and the Mystery of Golgotha, CW 167 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2015).