Recently, a rumor spread that Noam Chomsky, who was hospitalized in Brazil, had died.1 It turned out to be false, but it provides us an opportunity to remember the work of this 96-year-old intellectual at a time when the world is experiencing great turmoil on the international stage.

Noam Chomsky is considered by many to be the father of modern linguistics, an activist of the twentieth century, and the most quoted living author.

“Propaganda is to a democracy what the bludgeon is to a totalitarian state,”2 wrote Chomsky. The book Manufacturing Consent3 is probably his best-selling and most influential work. In it, he shows how the mass media in democratic societies, instead of objectively informing the public, function as a propaganda system that creates consent for the policies of the ruling elite and powerful corporate interests. They do this by distorting reality and limiting the spectrum of acceptable debate, even when lively debate is allowed within that spectrum. Even when there is no formal censorship, individual journalists are selected through a hiring process that filters out those who do not conform to the interests of the media conglomerates and internalize the assumptions of those in power. So there is no formal censorship but rather self-censorship by journalists and editors who instinctively follow the propaganda model. Unpatriotic reporting is increasingly punished with various more or less draconian methods. “An ideological structure, to be useful for some ruling class, must conceal the exercise of power by this class either by denying the facts, or more simply ignoring them—or by representing the special interests of this class as universal interests, so that it is seen as only natural that representatives of this class should determine social policy, in the general interest.”4

The Secrets of Words

In his latest book, The Secret of Words,5 Chomsky, along with his colleague Andrea Moro, offers a warning against artificial intelligence. In the form of a dialogue, the conversation begins with a critical examination of what Chomsky sees as misplaced euphoria in connection with artificial intelligence: its heavy reliance on statistical techniques and the analysis of large amounts of data to find patterns is unlikely to lead to true understanding. By emphasizing the complexity of human intelligence and the unique ability to understand and generate speech, Chomsky indicates that AI is not yet close to being able to replicate these distinctly human characteristics. Furthermore, while statistical AI may have practical applications, it is fundamentally insufficient as a scientific approach to really understand the nature of intelligent beings and cognition.

The subsequent detailed discussion of Moro’s ideas about so-called impossible languages—his specialty—indicates the existence of underlying structures in the brain that determine our ability to understand and use language and points to the possibility of innate grammatical structures as proposed by Chomsky’s theory of universal grammar.

Hope for Change

Few thinkers have been as critical of the intelligentsia as Chomsky: “If you are working 50 hours a week in a factory, you don’t have time to read 10 newspapers a day and go back to declassified government archives. But such people may have far-reaching insights into the way the world works.”6

Chomsky recognized that “as soon as questions of will or decision or reason or choice of action arise, human science is at a loss.”7 This sharp perspective has made the anarchist thinker one of the most outspoken political activists. “The intellectual tradition is one of servility to power, and if I didn’t betray it I’d be ashamed of myself.”8 Chomsky’s opposition to the Vietnam War and his criticism of US interventions in Latin America and the Middle East have made him a prominent figure in the anti-war, nuclear disarmament, environmental, and human rights movements.

As an Orthodox Jew and anti-apartheid campaigner growing up in South Africa, I was gripped by Chomsky’s ideas, especially on the politics of Israel. South Africa needed black labor, while Zionist Israel (my relatives there included) neither wanted nor needed Palestinians. Chomsky, therefore, argues that “In the Occupied Territories, what Israel is doing is much worse than apartheid. To call it apartheid is a gift to Israel, at least if by ‘apartheid’ you mean South African-style apartheid.”9 But it was not only this aspect of Chomsky that influenced me. He shed light on the often murky darkness of prejudice and bigotry and helped me to find words and ideas that allowed me to really explore the sources of injustice.

“If you assume that there’s no hope, you guarantee there will be no hope. If you assume that there is an instinct for freedom, there are opportunities to change things.”10

Translation Joshua Kelberman

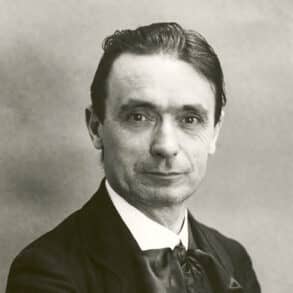

Photo Noam Chomsky in Massachusetts, 2017. Photo Source: Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Footnotes

- Since Chomsky suffered a severe stroke in June 2023, his wife has provided reports on his current state of health.

- Noam Chomsky, “On Propaganda,” WBAI, January 1992, last accessed Sept. 7, 2024.

- E. S. Herman and N. Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (New York: Pantheon, 1988, 2002).

- N. Chomsky, “Scholarship and Ideology: American Historians as ‘Experts in Legitimation’,” Social Scientist 1, no. 7 (Feb., 1973): 20–37; also in N. Chomsky, Towards a New Cold War: U.S. Foreign Policy from Vietnam to Reagan (New York: The New Press, 1982, 2003), 113.

- N. Chomsky and A. Moro, The Secrets of Words (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022).

- N. Chomsky, “The Professorial Provocateur,” New York Times (Nov. 2, 2003), last accessed Sept. 7, 2024.

- N. Chomsky, The Listener (April 6, 1978).

- Noam Chomsky interviewed by John Pilger, The Late Show, BBC (November 25, 1992).

- Noam Chomsky interviewed by Amy Goodman, Democracy Now! (Aug. 8, 2014), last accessed Sept. 7, 2024.

- Noam Chomsky interviewed by Fred Brankman, HotWired (Feb. 1997), last accessed Sept. 7, 2024.