In recent months, student protests against the Israel-Palestine War have emerged on university campuses, first in the United States, then in Europe and other countries. This wave of youth uprisings has been met with criticism, but what lies behind the division?

Seeing images of these protests, we are reminded of similar protests held against the Vietnam War and Apartheid in South Africa. The unspeakable suffering of the last eight months, beginning with the attack in Israel, erupted in one of the most contested and tense regions on Earth. These tensions, now manifesting as nightmarish death from violence, hunger, and illness, have a long history in spirit, thought, and rhetoric. Young protesters, many of whom are Jewish themselves, are calling on colleges and universities to divest from the State of Israel and the military industrial complex—specifically, to withdraw funds from endowments that have been invested in Israel—and they have subsequently been accused of antisemitism. Elders suggest that they are ignorant and naïve or that they are radicals possessed by narrow ideologies. Their critics are right in some instances, even if the criticism itself is impotent. For many young protesters, it is simply a matter of heeding the voice of their conscience as they witness how high-tech weaponry has led to the death of over ten thousand children trapped in a war zone without food, water, or shelter.

Images Without Reality

We are talking about a generation that has grown up with the internet and is moving with the velocities and influences that belong to this era. They have experienced a radical shift from text-based to image-based media. The speed with which a judgment can be communicated as an image far surpasses that of the written word. Images tend to connect more to feelings and are easier to remember, accompanied by buzzwords and slogans about antisemitism or terrorism. There is an immediacy to the mediation.

On the other hand, as intimately familiar as they are with social media and the internet, the younger generation also possesses a new discernment. The unreliability of what they experience online is a given—AI can create “realistic” images with a text prompt. However, even though young people know this and know that the internet is not trustworthy, it is difficult, since much of the digital world was designed not to enlighten or liberate but to possess—to grab and hold their attention. The ingenuity of psychologists and engineers set out to win in the “attention economy” and the financial celebrations of their successes, easily obscure the unconscionable fact that almost half of British teens currently feel that they are, indeed, addicted to social media.

In youth, idealism is a rite. Needless to say, it is intertwined with naivety. But it also comes with strengths, like the new instinctive awareness of the deceptive dimension of visual media. This can allow for more openness and less rigid polarization. The jaded stubbornness of many in the older generation might relate to their own digital naivety and an obsession with the rhetoric and logic of conflict. The natural tendency toward conservatism (not idealism) that comes with aging finds itself all too easily affirmed.

Distance is Not Enough

In the 1960s, many student movements were primarily cultural. Theodor Roszak observed, “What makes the youthful disaffiliation of our time a cultural phenomenon, rather than merely a political movement, is the fact that it strikes beyond ideology to the level of consciousness, seeking to transform our deepest sense of the self, the other, the environment.” The calls for freedom of speech, protest and assembly were not simply political. In 1970 M. C. Richards tried to present a justifiable interpretation of students demands for “self-fulfillment” for their professors: “Let us begin with the Self and its fulfillment. Self points to a dimension of being which is inclusive. It is the territory of the psyche: awake, asleep, and dreaming. Consciousness awake is art of a larger consciousness. This larger consciousness is called the unconscious, the superconscious, the psyche or the spiritual worlds … There is evidence that the territory of the psyche is objective can be researched, that the distinction formerly made between subject and object is undergoing a revision, that all experience is inner: that into all calculations must be read the calculator, into all measurements the measurer, into all scientific observations the observer.”

The youth of the 1960s experienced a field of living pictures, shot through with conscience and values, and tried to integrate them into life. This was an unparalleled awareness of the reality of the human spirit. The danger was to lose orientation on the earth. Connecting the human spirit to the spirit of the world did not achieve widespread or mature realization. Today, young people experience a field of technologically mediated moving and interactive pictures coming from without. The images can connect or they can dampen thinking and “self-expression” and its deeper moral power and potential for renewal.

As the terrible bell of the conscience tolls, not only over the Middle East, but also Ukraine, Sudan, and Haiti, young people are challenged to maintain orientation as they use the new technologies. Peace requires this. They must also find spiritual resources that can counter the powerful forces of destruction we are coming to experience in ourselves. May the sobriety they are learning as digital natives assist them in this task. The future of the Earth is linked to loyalty to the horizon that stretches between the moving images of the spirit and those of our new technologies.

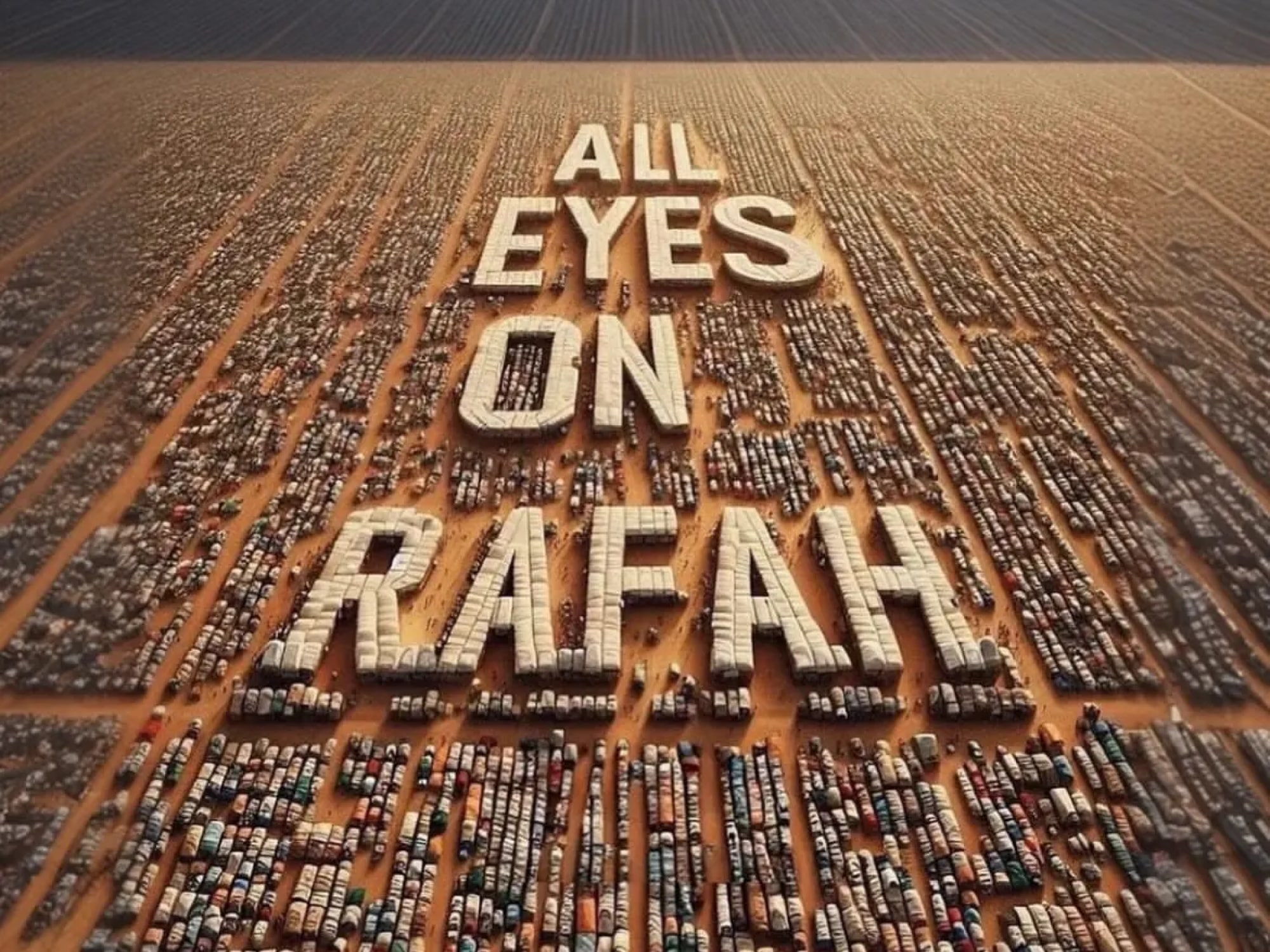

Image All Eyes on Rafah. The AI-produced image has been shared more than 40 million times on Instagram. Source: Wikimedia

One can celebrate that students are standing up for peace, and questioning the billions of dollars of weapons that the US sends to Israel. But where was the love of peace when it came to the war in Ukraine? Russia invaded because they could not accept a hostile state with military bases on their border. If Ukraine had committed to not joining NATO and to respecting the Minsk accords, there would have been no invastion. Glen Greenwald does the best reporting on US foreign policy. I believe he has pointed out that 10 or 20 times more people have died in the Ukraine war. The students should demand a Peace movement, and demand that the military and intelligence agencies stop running the country. Now we see that NATO, a military alliance, controls European foreign policy. The real problem is the power of the military industrial complex which is connected to the surveillance security complex in both Europe and the USA.

Brilliant insights into the challenges of mediated experience that is now planted on a cellular level in the rising generations. Discernment, discernment, discernment. We (however we self-define) need to recognize and cultivate a moral compass that could point us toward peace. This article is a step. The current protest movement is a powerful allergic reaction to an infected system. We certainly see the symptoms, the illness, and the resultant suffering. Intentional human sacrifice in the name of religion or country doesn’t seem like a practice from the distant past any more. Instead, aided by new media, it presents a whole new seemingly intractable problem—until we find a way to value every single life.