Often, even just a few days after September 29, we forget about Michaelmas. But the deeper atmosphere of this festival runs throughout the year and is part of the great spiritual celebration that we are able to experience, even in these difficult times. Following on the pandemic mega-event and the outbreak of war in Europe, it’s worth taking a look at an unusual painting in Madeira.

One day, as I was walking down a narrow street of Funchal, the capital of Madeira, an island off the coast of Portugal, I happened to come across the old door of the Sacred Art Museum. At the time, I was visiting this wonderful small paradise of rocks and flowers in the middle of the Atlantic, at the suggestion of a Waldorf education pioneer. I was wondering if there was any motif of Michael and the dragon known to the inhabitants of this solitary place in the sea since the time of its discovery by the Portuguese in 1419. So, out of sheer curiosity, I searched all the rooms of the museum and found . . . nothing. After speaking with the director, I learned that the museum did have something on the subject, only not in the main rooms. I was led to the foyer, on a poorly lit landing, where an old painting, a lonely ornament, hung on the wall. I was immediately struck by several details.

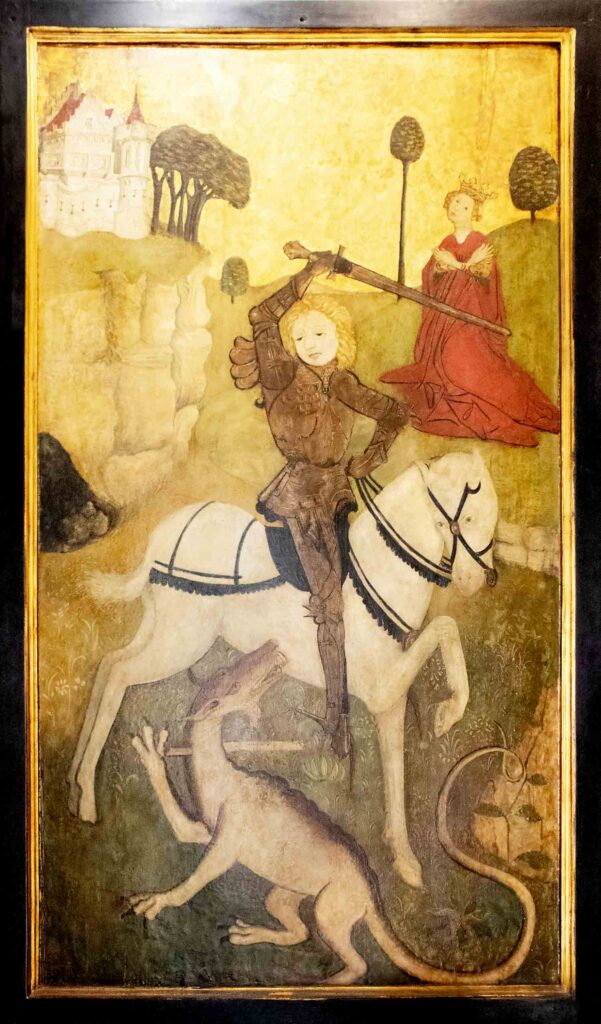

The monster made his home in a gloomy, soundproof cave under a rocky cliff—the ideal, dark dwelling place of Ahriman in his connection with the mineral world, the kingdom of nature with the most dense and inorganic substances on the planet. On top of the cliff is a strongly fortified citadel, symbolizing an ancient community of people, still sheltered within themselves and isolated from the rest of the world. The monster has left its underground lair and entered the living, green, organic outer world. A delicate female figure in the background appears to me to be a symbol of the individual soul, a human ‘I’ that has freed herself from the secluded and sleepy social milieu of the citadel. She now finds herself in inhospitable, mountainous terrain and must pass the first bitter trial of freedom: utter loneliness. The red toga that envelopes her seems to emphasize her power of will, while her arms, crossed in front of her heart, express an inner gesture of quiet and love.

Throughout the centuries, Michael has been depicted in numerous iconographic representations around the world, either as a fearless soldier in full armor, standing with his foot upon the monster itself, or else as an imposing warrior, or even as a winged superhuman figure soaring to heavenly heights, sometimes accompanied by armed angels, all fighting against the dragon together. These various archetypal representations have their origins, above all, in the Christian and Jewish traditions and, interestingly, though less known, in the “Mika’il” of Islam (Koran Sura 2:98).

Inner Stillness and Determination

Notice how in this painting (with its somewhat secret existence in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean), Michael, unlike in most emblematic representations, does not attempt to attack, overpower, injure, or kill the monster. His sword is raised but is in no way directed at the beast, and actually, in perspective, his humble weapon seems more like a spiritual shield protecting the human figure in the background. Michael rides a shining, white horse, full of vitality. The horse performs a piaffe, a complex riding step that requires extremely precise mastery and is one of the most difficult steps in horsemanship. Michael’s physiognomy does not give off the martial zeal of, say, an impetuous samurai warrior. His gaze is not even directed at his opponent. His whole face shows composure and inner stillness, accompanied by firm determination. The horse’s facial expression also, surprisingly, reflects these same characteristic features.

It’s interesting to compare this with other depictions, where the confrontation between Michael and the dragon appears quite differently. In one example, Michael is shown just after an attack on the monster from a distance with a lance. The sharp spear has wounded the monster, but the piercing weapon broke and lies bloodied on the ground. Another variant shows the broken remains of the lance on the ground and Michael lunging for the decisive blow with a mighty, shining sword.

One remarkable feature of this unusual image in Madeira is that the dragon appears without its most famous attribute—there are no flames shooting from its mouth. On closer inspection, we find the reason: a thick tree branch has pierced the monster’s throat! Both ends of the branch are rough and splintered, neither having a sharp point suitable for penetration. We might consider that perhaps it was the unique and courageous work of human beings who, in collaboration with Michael, acted beforehand while the monster was still spitting flames.

In Community with Michael

This detail throws light on a still little-understood feature of the Michael imagination. Perhaps we should not imagine Michael as a being who acts alone, on his own. In order to confront the many abysses we are all currently facing around the world, each of us can take up a collaborative effort, both social and spiritual, in community with Michael—an effort that is appropriate to these new challenges. The famous flames from the dragon’s mouth could be compared with the speeches given today, pouring forth in torrents from the mouths of the media and public figures, aiming to permeate our mass consciousness. As the dictatorial spectacle of 1933 showed, words have hypnotic power. The untreated social carcinoma of 1914–1918 (as described by Rudolf Steiner) is still felt today. Its aim, among other things, is to block the cultural contribution of spiritual science, as well as the growing social fellowship of rising generations. This is reminiscent of the tyranny of the medieval church, which in 869 [at the Fourth Council of Constantinople] suppressed the idea that the spirit was an essential part of the human constitution and thereby opened the door to materialism and an irrational fear of death.

Trust in Our Own Strength

In this unusual painting, a simple tree branch was felled and purposefully employed, collaboratively, by human beings. It could be a symbol of what needs to be practiced in society today, collectively, and cultivated in the spiritual depths of each individual, in addition to their material efforts. It is a practice of trusting in our own innate powers and in the constant presence of Christ and the hierarchies, who wisely guide the great evolutionary steps of humanity. In the biography of every human being, there are moments of crisis (from the Greek [krísis] meaning “[turning point], transition to a new stage,” [ultimately, from krīnō, “decision”]) that encourage new steps forward in the development of consciousness and in the ability to work in the great university called Earth. The latest trial of barbaric wars in the heart of Europe and the Middle East, and all the unforeseeable consequences for the entire planet, is yet another opportunity for all of us to collaborate in the universal mission of Michael as an ally of Christ in his new etheric revelation.

George and Michael

Michael’s spiritual figure as an archangel (today elevated to an archai) has been known for millennia in different cultures across the world, through a variety of representations. In the course of recent history, mostly for political and ecclesiastical reasons, Michael was brought into a parallel relationship with the mythological human figure of Saint George. This was most prevalent during the colonial expansion of the British Empire, so that even today the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is awarded by King Charles to those personalities with significantly worthy merits.

We are all familiar with it, this sign which represents a supernatural being—be it Archangel Michael or Saint George—trampling upon and overcoming the dragon. This is the pictorial representation of the third Christ event: the Archangel Michael or Saint George, the later Nathanian Jesus boy, permeated by the Christ-being. Hence the archangelic figure in the spiritual worlds. And the overcoming of the dragon means the subjugation of the uncontrolled passionate nature of human beings in their thinking, feeling, and willing, which throws thinking, feeling, and willing into confusion, into disorder. 1

In the times preceding our current development of thought, there was already forming a forerunner of a picture that projects into our time, but is not yet properly understood. At the end of Atlantean times, when Christ permeated the soul who later became Jesus of Nazareth, this brought it about that a being now existed who always mastered the wild and confused storming affects, who was victor over all densified structures of thinking, feeling, and willing. Humanity represented this to itself in the picture of St. George or St. Michael, the dragon conqueror. This is a direct imaginative expression of the third forerunner of the event of Golgotha. 2

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Footnotes

- Translated from the German. See Rudolf Steiner, The Fifth Gospel: From the Akashic Record, CW 148 (Rudolf Steiner Press, 1985), lecture in Berlin on February 10, 1914.

- Translated from the German. See Rudolf Steiner, Approaching the Mystery of Golgotha, CW 152 (SteinerBooks, 2006), lecture in Munich on March 30, 1914.