María Corina Machado has been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “for her tireless work promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela and for her struggle to achieve a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy.”1 But critics are unnerved by her proximity to right-wing groups2 and her dedication of the prize to the US president for “his support of our cause [of freedom and democracy].”3 Rebuilding a broken Venezuela requires politics beyond ideology, so the author sets aside these criticisms to highlight Machado’s positive work.

María Corina Machado (born 1967, Caracas) grew up in a family of entrepreneurs. Her mother, Corina Parisca Pérez, a psychologist and former tennis player, and her father, Henrique Machado Zuloaga, a steel-industry businessman, embodied a philosophy of work, study, and service that inspired their daughter to pursue a public career. As an industrial engineer specializing in finance, she was selected for the Yale World Fellows program in 2009. Long before she became a national personality, she co-founded social initiatives. In 2002, she co-founded the NGO Súmate (“Join in”), a volunteer civil association dedicated to election monitoring, citizen participation, and civic education. Her commitment to a strictly civil society approach has led to court proceedings, smear campaigns, and surveillance.

She was elected to parliament in 2010, where she was able to bring her directness and debating skills to the fore. In a 2012 speech that made a lasting impression on the public, she told then-President Hugo Chávez: “expropriation… is stealing.”4 She paid a high price for this candor: physical attacks in the National Assembly (where she suffered a broken nose), travel restrictions, and administrative bans. When she was not allowed to speak as a member of parliament before the Organization of American States in 2014, she still brought forward her condemnation of abuses from the seat provided by Panama. As a result, she lost her political mandate, but she gained international visibility—at the cost of further harassment. Since then, she has emphasized that her struggle is a spiritual one—a struggle between fear and dignity, truth and lies, carried forward by belief, conscience, and civic responsibility. And she emphasizes something else: she does not speak for herself but for the movement and for the people. That is why her message is one of pluralism: it is up to us; we will make it happen. But her greatest contribution is not a slogan, it’s a method: organize, unite, persevere.

Into the Underground

In 2023, despite her exclusion, she led an opposition primary and won with an overwhelming majority of 92.35 percent of the vote, with nearly three million ballots cast. This allowed her to reorganize widely disparate forces. But the government barred her from running in 2024, so she named a replacement candidate: philosopher and professor Corina Yoris, who was already acting as leader of the citizens’ movement. The system blocked Yoris’ registration as a candidate, and so Edmundo González Urrutia appeared on the scene—an experienced diplomat with little name recognition but who was perceived as a calm and fatherly personality. During the 2024 presidential elections, hundreds of thousands of volunteers collected and digitized tens of thousands of official tallies to verify the results using the same tools as the system. According to most of the tabulations, the opposition’s count showed González Urrutia with a lead of about 70 percent of the votes, even though several million Venezuelans at home and abroad were denied their right to vote. The victory was not recognized by the regime, and the National Electoral Council did not publish any detailed results. From that point on, the repression intensified: arrests, forced exile, and deaths. Machado decided to seek safety. Since the end of 2024, she has been forced to work underground, but she has promised not to leave Venezuela until the democratic goal is achieved. Her presence at the Nobel ceremony in Oslo this December is uncertain. In January 2025, when she participated in a demonstration, she was detained for hours, forced to record a video, and released after immediate international pressure. Meanwhile, her closest collaborators are being persecuted: some are imprisoned, others have had to leave the country. In May 2025, Operation Guacamaya enabled five of her closest collaborators to be smuggled out of the Argentine embassy in Caracas, which had been heavily besieged for months.

Perseverance

One characteristic explains the Machado phenomenon especially well: perseverance. In a landscape with shifting boundaries, she sticks to the same compass: freedom in cultural and civic life, equality before the law, and practiced fellowship in action. This consistency gives her the credibility to unite the people’s will and devise strategies that seemed impossible: linking data and the streets, tabulations, and an embrace. But there’s also her femininity, not as some rallying “-ism,” but as a way of being: caring, supporting, restoring. Her message doesn’t put forward figures but reunites families. In a country that has lost nearly a quarter of its population, this image carries the weight of a civil sacrament: “embracing [each other] again”5 is not sentimental nostalgia but a program. She expresses it in her subtle gestures—listening, comforting, insisting without demeaning—and in a quiet determination that does not confuse peace with surrender. Peace requires tried and tested truth, justice without revenge, and trust in the abilities of each individual. The Sakharov Prize (European Parliament, 2024) and the Václav Havel Prize (Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, 2024) have already recognized this combination of courage and commitment, freedom of conscience, and effective defense of human rights. Machado was unable to accept them personally. Perhaps she will also be unable to travel to the Nobel Prize ceremony. But her influence is already making waves: a transnational network of Venezuelans—both inside and outside the country—that has transformed hope into volunteer work and outrage into actionable protocols.

Translation Joshua Kelberman

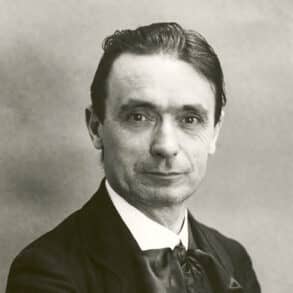

Image María Corina Machado; Photo: Bel Pedrosa (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Footnotes

- “Nobel Peace Prize 2025 – Press release,” NobelPrize.org, October 10 2025.

- In September 2025, Machado appeared at the Europa Viva conference in Madrid, organized by Patriots for Europe, the far-right faction of the European Parliament.

- María Corina Machado (@MariaCorinaYA), X post, October 10, 2025, 3:34 PM:

This recognition of the struggle of all Venezuelans is a boost to conclude our task: to conquer Freedom.

We are on the threshold of victory and today, more than ever, we count on President Trump, the people of the United States, the peoples of Latin America, and the democratic nations of the world as our principal allies to achieve Freedom and democracy.

I dedicate this prize to the suffering people of Venezuela and to President Trump for his decisive support of our cause! - Victor Mata, “The tragedy of Venezuela’s socialism,” Acton Institute Commentary, July 3, 2018.

- María Corina Machado, “Up Close and Personal: A Conversation with María Corina Machado,” Liberal International, accessed November 1, 2025.