In October 2024, Zacharie Dusingizimana spoke at the international conference for Inclusive Social Development at the Goetheanum. He told of the great pain that still characterizes his home country, Rwanda, and how we learn to heal by asking the right questions.

At the heart of Rudolf Steiner’s work is the question of freedom: How do I become a free human being, able to live and act out of who I truly am? How do I find the source for what I do in the deepest core of my own being? How can I go beyond the thoughts and patterns imprinted in my body, in my habits, in the society around me, and find my true, original self? Inclusive social development is also about just that.

I am from Rwanda, in Central East Africa, and I want to tell you part of my story: What led me to be here today, as the co-founder and director of Ubumwe Community Center, and as a human being on a journey of healing others and healing myself.

Thirty years ago, I was 17 years old and coming home for the Easter holidays from the boarding school I was attending. I didn’t know that this was going to be the beginning of a new life, in a new world, and with new people. I was born into a very modest family. My father was an artist, carving wooden sculptures, and my mother was a homemaker. We were living a peaceful life, very proud and thankful for what we had. I was one of six siblings, two boys and four girls. At the time, three were living far away while the rest of us were at home, including myself.

On the morning of April 7, 1994, we heard on the radio that the President of Rwanda had been killed in an airplane that was shot down as it was landing in Kigali, the capital city. It was not very clear what was happening—the only news we could get was from the radio, and the radio only repeated the message that everyone was to stay at home. I could see our parents and neighbors gather in small groups, but could not imagine what was going on, or what would happen after that. A few days later, we started to see houses burning all around us, in all the surrounding villages, and I could hear the loud shouting of many people, running, searching for a place to hide. This is how the genocide against the Tutsi started in my village.

The three months of genocide were like dying every day and coming back to life again! The whole country lost over one million people in only 100 days. After the genocide, we were all traumatized in different ways, just like everyone else. As for myself, I became very frightened by everyone and everything. I could sense the smell of dead bodies everywhere. The next year, 1995, my family and I moved to live in Nairobi, Kenya. This felt very far from my country, with diverse cultures and people. I spent almost five years there. My wish was to forget about my country and never go back there. At the end of 1999, one of my sisters, who had stayed in Rwanda, came to visit us in Nairobi. I was completing my secondary school at that time. She explained to me that things had changed back home and invited me to come, just for a visit, and then return to Kenya. When I came to visit, of course, not everything was right, but at least I could see people together. I could see students going to school, and everyone was going after their business, to make a living. And the very important thing was that there were no gun sounds, and I did not hear voices of people shouting for help anywhere. During my visit, I started to regret that I had run away while others who had survived, had stayed, had joined the army, or were doing different kinds of work to contribute to their community and help the country recover from the genocide. I felt an emptiness inside me that I wished to fill.

The Crucial Question

I was in Gisenyi, a city on the Northern shore of Lake Kivu, with a backdrop of volcanic mountains, right on the border to the Democratic Republic of Congo. As I was walking by the side of the great lake, I crossed paths with a group of people from the US. Unexpectedly, one of them turned to me and asked: “Who are you?” Surprised and confused, I responded: “I’m fine.” But she asked again, and eventually, I understood what the question was. “Who am I?”

The group was there to support one of the orphanages outside of Gisenyi, Imbabazi, which had been founded by an American woman after the genocide. As they told me about their work, I asked if I could join them the following day, just as a volunteer. Meeting those very young kids—between the ages of 2 and 15—at the orphanage, I couldn’t stop imagining what might have happened to their families and what they must have faced during the genocide. I began to feel that the orphanage was the right place for me to make my contribution, and I started to feel like an elder brother to them. I decided to stay in Gisenyi to work with these children. Then, in 2003, I moved to the orphanage to stay with them.

The question I had been asked at the shore of Lake Kivu before I started my first job at the orphanage 24 years ago was: “Who are you?” I am still asking myself the same question: “Who am I?” Who am I, to do what I do? And who am I, to be here today, celebrating 100 years of inclusive social development? Now, I get this opportunity to ask you the same question: “Who are you?” Who are you, to be here after these 100 years? And what have you done, or are you doing, to find yourself here?

Over time, the children at the orphanage started to tell me what had happened to them and their families, as they were participating in the healing process and family tracking programs. Many of them have now been reunited with their families or relatives, and the others received care and education in other ways. Today, they are all grown up, and many have their own families.

A special person that I met on my very first day at the orphanage was Frederick, a boy who had lost both his hands during an attack by the perpetrators of the genocide who were trying to come back into the country from the DRC in 1998, to try and complete what they had started in 1994. It is from Frederick that the inspiration came to also do something to support persons with disabilities. Every time we went into town, we saw that there were many people with various disabilities, many of them genocide survivors, living on the street in very vulnerable conditions.

In 2005, we founded the Ubumwe Community Center (UCC) together to support other people with disabilities, like Frederick himself. We began in a small room that was offered to us by a local church. We invited people in, and because they saw that Frederick also had a disability, they trusted us, and they came. In the beginning, we did not know what we were doing, but we both knew how to read and write, and many of them did not, so we began by offering literacy classes. Once we started, it became clearer, step by step, what the real needs were. Over time, we developed the programs that now make up UCC, to respond to those needs. And in the process, we discovered and learned how to do that.

Learning to Walk in Each Other’s Shoes

The orphanage closed in 2012, and yet we still meet once a year to remember the woman who founded it. After my time at the orphanage, I have continued working with the mission of UCC until now. And now, I am here, and you are all here. This inclusive spirit of Rudolf Steiner has been chasing us all around the world, forcing us to find each other and trying to bring all of us together because we are one!

Let me share with you one more story from the world that I am in every day at UCC. A few years ago, a woman entered my office, followed by a friendly-looking young boy. I had not met the woman before, but I recognized the boy because he had been part of our community for some time. I offered them a seat, but before even greeting me, the woman immediately asked the question that had brought her to me: “Where would my son be if I died?” I was surprised—I had not expected such a greeting! Because I did not know exactly where this kind of introduction would lead us, I assured her that nobody was going to die. She paused, and we looked at each other for some time; then, she began to talk about what had happened to her and her son.

The mother was a survivor of the genocide against the Tutsi. I sat, listening to her as she told me how she had survived, how she had seen her husband and three children murdered in front of her eyes, and how her entire family of more than 15 members had all been killed. She was the only one in her family to survive. After the genocide, with scars all over her body, she was traumatized like many others. Starting over was not easy because she was hurt physically and emotionally. A few years later, she decided to remarry so that she could build a new family. Her firstborn in that new family was this boy with Down syndrome, who was now with her in my office. After all she had been through, she started yet another journey of stigmatization and exclusion from the community. Some close friends advised her to get rid of the boy. They were marginalized to the point where even her new husband left them. So, it was just her and the boy. However, the mother did not give up, as she really loved her son. She did what she could to raise him until he turned 16. Then, she decided to sell a part of her land so that she could move close to our center, where the boy could get an education because other schools would not accept him. They moved to our town, and the boy started in our special needs program. When he came, he did not speak, but now he has started to talk a bit, and he seems to enjoy being with others.

And now, she had come to my office to ask me: “Where would my son be if I died?” What had brought her to ask that question?

The money she had received, when she had sold her land, had run out. She had used it to rent a house near our center. Now, she was struggling to pay the rent, and even getting daily food was becoming complicated. And so, she had decided to kill herself, together with the boy. She had made a plan to go to one of the biggest rivers in Rwanda, the Akagera River, which is the source of the Nile. Together with the boy, she took the bus from Gisenyi to the river. Lake Kivu was near their house, but she did not want their bodies to be found. She had chosen the big river so that their bodies would be taken far away. When they reached the river, she told her son that they were going down to the water, just to wash their hands and faces. But the boy refused to go. She spent hours, unable to convince him to go down with her, to the river. He did not move. They were on a main road, and there were traffic police who had been observing them from a distance. When it was getting dark, the policemen approached them to ask why they were there, and what they were doing. The mother told them that they were waiting for someone to pick them up, but that the person had not shown up and they didn’t have bus fees to go back home. The police officers gave them some money and helped them get on a bus back to Gisenyi.

Two days after they had survived this dark moment, they came to me, and now she was here, greeting me with her question: “Where will my son be if I die?” Before I answered, I asked myself again: “Who am I? Who am I, to answer such questions?” Without hesitating, I assured the woman that she was not going to die, and that if it did happen for any reason, other than suicide, the boy will be ours. Then, she began to cry. I felt confused and did not know what to make of this, but I remained calm and simply waited to see what would happen next. When she had collected herself and could speak again, she explained that she was crying, because she was so relieved and happy to hear that her son would have a place to be. After a pause, she added that she had not felt this happy and assured in almost 26 years of suffering. “Who am I?” Who am I, to have answered this question? Right now, we are trying to support her with what we can to keep her and the boy safe.

Rudolf Steiner spoke about how we find our way to each other when we are seeking the spirit with a shared purpose. He also emphasized the importance of learning to learn for the whole of our lives. My life after the genocide and my experiences at the orphanage have shaped me into who I am now, through a progressive healing of myself, while healing others, who do not have anyone else to do so. Meeting this mother and listening to her journey of 26 years made me forget all my worries and challenges because mine seemed insignificant compared to hers. She contributed silently to my healing while looking for someone to support and heal her. Having met her, I found the resolve never to complain anymore and just to act in a positive way. I also learned that one of the most important educational methods in our domain of intervention is to be “listening and listening again.” By doing so, we understand; we forget ourselves and put ourselves in the shoes of the other person, who is seeking our help. And in doing this, we learn to learn, for the rest of our lives.

This is who I think I am now. And who are you?

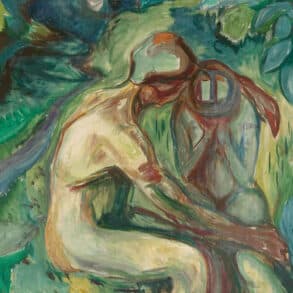

Images Impressions from the Ubumwe Community Center in Gisenyi, Rwanda

I feel the need to comment again and ask the question – what in Anthroposophy has ever been exclusive to anybody in the world? Why the need today to bring in the word “inclusive” in any official context? It implies exclusivity or the need to change something that used to be exclusive to what we now proudly announce will be inclusive! In times when words must be used ever more cautiously and with thought, this is standing out for me and bringing up the whole question of integrity in our day and time of so much division and false propagandist slogans. Language is being seriously eroded to change the meaning of words or make them interchangeable, devoid of any real meaning or even to weaponize language. In such an environment we as anthroposophists must be acutely aware of our own use of words and do our best to maintain the integrity of language and meaning. This is why the naming of this section rang alarm bells for me.

This question has taken on new dimensions in me, after reading these lines! Thank you!