The Sahara is particularly well-suited to questioning our ideas of boundaries and transitions, of the future, of freedom, and of resilience. Has Europe had its day? Will impulses for the future come from other parts of the world? With its focus on this great desert, the Culturescapes Festival 2023 in Basel, Switzerland, aims to add fuel to these questions.

Jurriaan Cooiman, founder of the Culturescapes festival, looks rather tired during our first Zoom call. It’s just before the festival starts, and I can imagine the work he and his team have had to do over the past months and, ultimately, years. Some of the roots for this festival lie, in fact, in Dornach. The then 19-year-old Cooiman came to the Goetheanum in 1986 as a stagehand from Holland and the Youth Section there. After studying eurythmy with Werner Barfod and a year on the stage with Else Klink, he returned to Dornach once again. He remained with the Goetheanum Stage as a eurythmist until 1997. Starting in 1995, he began to organise music festivals in Dornach in close collaboration with Michael Kurtz (Sofia Gubaidulina’s biographer and collaborator at the Section for the Performing Arts). They featured Gubaidulina, Anton Webern, György Kurtág, Béla Bartók and Johann Sebastian Bach. Some might still remember them.

Cooiman’s idea and question even back then was how to bring contemporary music and other art forms into play with each other, into inspiration. He was interested in the creative cosmos that emerges when art inspires other art reciprocally. Perhaps this is connected with the life forces, which are manifold in this big world. The Goetheanum became too cramped for the now not-quite-so-young Cooiman. He wanted to create connections in the world, which is why he started his own business as a manager in the arts and founded PASS (Performing Art Services) with Rembert Biemond.

Entirely out of his own interests, he organised the first Culturescapes festival in 2003. It started with the cultural landscape of countries on the other side of the Iron Curtain—their church architecture, their poetry, their culture—focusing first on Georgia, followed by Ukraine, then Armenia. “Strange coincidences often occurred.” For example, while Culturescapes Georgia was taking place in Basel, the Rose Revolution was going on in this country in the Caucasus. The Orange Revolution in Ukraine took place while spaces were being opened up in Basel for Ukrainian culture. It was as if history could be experienced “in the making”.

Over the past 20 years, a network of more than 50 partners from the Swiss cultural scene has emerged who help to make Culturescapes a reality. The Edith Maryon Foundation helps with the financing. Two cantons are involved. The SDC (Swiss Agency for Development Cooperation) and Hoffmann-La Roche provide support with large sums of money. Katrin Grögel, head of the cultural office of the city of Basel, Sibel Arslan, member of the board of trustees of Culturescapes, and Yarri Kamara, artistic advisor of Culturescapes Sahara, will speak at the opening. It is clear: the festival makes a cultural contribution that carries weight in Basel.

The Inner Concern

Cooiman wanted and wants to create immediacy, to dismantle narratives, to question the images we have and thus also ourselves. By way of questioning, he creates movement through encounters. His co-curator, Kateryna Botanova, has been supporting him in doing so since 2014. In this, he has remained a eurythmist, if you will. Cultural exchange, as the core activity, seeks to facilitate transformations in our habits of thought. In the garment of art, however, we are free to be moved. Initially held every year for three to four weeks, Culturescapes’ most recent “works” now last two months and take place every two years.

Cooiman uses the free cultural spaces and brings new, unknown content in them—content that is foreign to us at first. He does this in the very clear awareness that Europe has “had its day”. “Europe has become a province that should, for once, display some modesty. The belief in progress comes from Europe, but there is development everywhere” he says, and a touch of bitterness echoes in his words. Or is it, here, too, exhaustion from the fact that the idiocy around progress—believing that improvement, measured in monetary profit, while exploiting resources, is what’s best for humanity—has been raging for decades, and we are not taking responsibility for it? “Europe’s systems thinking is not compatible with planet earth. The intellectual horizon of 2023 is very different from a hundred years ago. Do we perceive this?” Culturescapes wants to show the diversity of the sources in this world. Cooiman sees being able to celebrate diversity as a peace offering. Putting ourselves in other people’s shoes is essential for solidarity. Here, the part of him that sees itself as having a political responsibility speaks.

Cultural Exchange is Geopolitical

There have been growth steps in the biography of Culturescapes. One of these was the decision in 2015 to see itself as biennial. Moreover, the team of curators wanted to dissolve the self-reference to Europe. Then came the orientation towards ecosystems, biospheres, and regions. That was the turn towards the geopolitical and away from nation-states. “Critical zones” interested the makers of the festival. The complex interrelationships of our human existence light up more clearly through them. The Amazon was the focus of the 2021 festival, and with it, the question of water, cycles, nature, and climate. In one of the discussions about forests and development, the SDC offered its help, whereupon an invited Yanomami shaman asked only to be “left alone for once”, Jurriaan Cooiman recalls with a smile. It was a key moment for him that showed how we think about ourselves. That can serve as a wake-up call. Afterwards, the shaman was keen to climb the Swiss mountains, so a tour by train up to the Jungfrau was organised for him, Cooiman continues. The shaman needed a moment. “You have built serpents through the earth, and I had to ask my gods for permission to pass through with my spirituality.”

Indigenous people, with their view of the world, give us an opportunity for the self-awareness of how we are ultimately destroying the earth. They do not hold it against us. “When they perceive how we are treating the planet, they want to help us get out of our predicament,” is how Cooiman sees it. Are we then not exploiting the view of the human being and the world of indigenous people for ourselves in order to heal our lack of empathy? For those who create Culturescapes, the question is: with what privileges and with what attitude are we working—do we simply take it, or do we respect it? The festival sees itself as a wedge into what is possible. “It’s not about having; it’s about being. We need a new, different togetherness. We do not look at our society in its diversity and reduce it to a binary system made by patriarchal people in power. A different future is possible. But we don’t have much time left.” It is here that Culturescapes wants to stimulate and contribute to going out of ourselves into the world and also to making the diversity in Switzerland visible.

The Desert is an Animated Land

The now seventeenth edition of Culturescapes Basel has chosen the Sahara as its region and thematic focus, but not without context. Every year, millions of tonnes of Saharan dust blow across the Atlantic to the Amazon, creating fertile soil. The great desert lives in the cycles of this planet that ignore the boundaries drawn by colonial powers. At the same time, the “route of death” runs right through it—a route where people fleeing to Europe often perish. The Sahara is a boundary at different levels of interpretation. It divides the continent in our consciousness into a north and a south.

There is no reason for this, says Cameroonian political scientist and historian Achille Mbembe. And yet, it has to be traversed, it must be overcome in order to get to Europe. The Sahara is hot, cold, harsh, barren, vast, great, and very close to the stars at night. “For the peoples of the greater Sahara-Sahel region, resistance, struggle, and survival are a way of life. Violence and suffering are a daily reality for many. The vocabulary of the global North has an appropriate word for it —resilience,” says Kateryna Botanova. However, calling something resilience that arises from difficult life circumstances trivialises the price that is paid for it. Can we endure resilience as an ambiguous term? And what would a non-resilient life, but one worth living, look like in the Sahara?

The Sahara is an entity that we in Europe do not understand a great deal about. The Tuareg, one of the nomadic peoples of the great desert, know the necessity of keeping moving. When they stop travelling, “essuf”, the great emptiness, appears. So, what are the images and visions of the Sahara? What are the things they and their people tell us if we can hear them? Does the Sahara make it easier to talk about boundaries, images of the human being, migration, and postcolonialism? The triangular relationship between Europe, Africa, and South America has a sorrowful, fateful history. Today, we have to question the narratives that have emerged from this. “We need a meta-level attentiveness as to how the general debate is going right now,” Cooiman says. Contemporary discourse has political weight and plays into the cultural sphere. That is why Cooiman makes no distinction between activism and artistic activity. He brings the term artivism into play, which has its roots in the Mexican political art scene of the late 1990s. Anyone wishing to educate themselves on this is referred to the “Basel Colonial City Tour” in the programme.

Just as the Amazon is the green lung of the earth, Africa is the spiritual lung of the world, says the Senegalese economist and humanities scholar Felwine Sarr.1 He was commissioned by Emmanuel Macron to prepare, along with Bénédicte Savoy, the return of art looted by France from Africa. Back in June, Sarr was in Basel at the Kunstmuseum, in cooperation with Culturescapes, to read from his novel. His play Traces was shown at the Neues Theatre in Dornach on November 2. On November 4, there will also be the pan-African dance competition “Africa Simply the Best”, where solo dancers will present their work.

Concrete Art

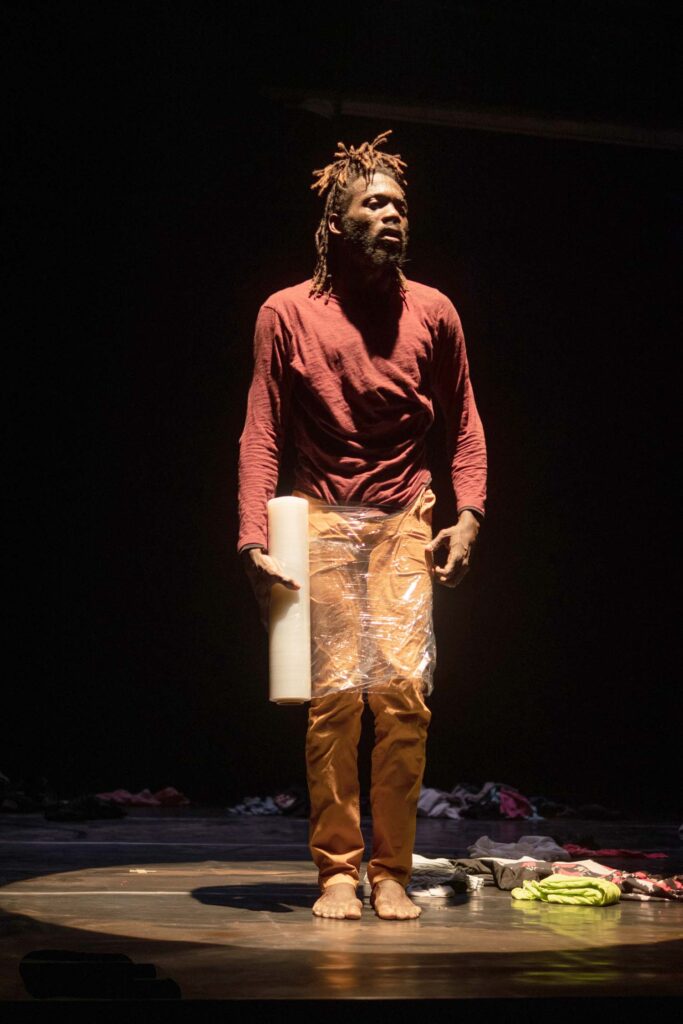

For the opening on October 1, the Burkinabe-Belgian choreographer and dancer Serge Aimé Coulibaly presented his dance piece, C la vie: a wild physical frenzy of movement, driven by drum rhythms and leading almost into ecstasy, on the rather small stage of the Schauspielhaus Basel. Africa gets up close and personal. The breath and sweat of the eight dancers are heard and seen, perhaps even felt in the front rows. I think of possession rituals in West Africa. Here, a completely different force tells of life, compared to the eurythmy ensemble’s performance of the Foundation Stone verse that I saw recently at the Goetheanum World Conference. My statement has nothing whatsoever to do with being judgemental. I see that the movements of some of the African dancers are not brought quite cleanly to completion, as I am used to seeing in eurythmy, for example. And I see that I see it that way—a little shocked but also happy about this self-awareness. I note that this dance creation is generated from other sources—it has not been wrapped into the perfect form to the same extent. And I ask myself why I expect that from art. We look first for the familiar. The unfamiliar can show itself when the familiar is not deemed to be universally valid. Then I really do start to behold differently. I would like to know how the choreographer Coulibaly worked with the dancers. Does Africa’s life, and therefore also its creation of art, perhaps connect much more strongly with the forces of the earth, of momentum, of constant flow, of giving birth, and the power of fire? Or does that point of view also stem from my Eurocentrism?

A rich, first-rate and sophisticated programme can be found on the Culturescapes website. In film, dance, performance, music, literature, lectures, discussions, guided tours, and even master symposia, the Sahara region serves this year to encourage movement. Almost eighty artists are involved. Nothing folkloristic seeks to sweetly entwine and lure us into the dollhouse of other cultures that, after all, only exists in our own minds. Every cultural exchange, in the sense of beholding, is a profoundly serious matter. This is where people meet, at best, in the awareness of their diversity. The future can arise from encounters because change is possible. “There is not just one future,” Cooiman says. “There are many options, and there are different futures depending on where I was born. This may also mean that other regions will take on the leading role for the further development of humanity while Europe ages.” The question as to the future also relates to new epistemological models. Broadening our view, not only looking from a rational perspective, will help us to outgrow our own bubble.

In 2025, the Sahara will once again be the focus of Culturescape—that is something Cooiman and Botanova already know. The team of curators wants to delve deeper. It is not, therefore, about delivering a product that sells well for one season. It is about bringing the “Black Continent” with its secrets and creative powers, its images and world questions, a little closer to us.

More Culturescapes

Performances «Traces – Discours aux Nations Africaines» and Laureates of Africa Simply the Best

Translation Christian von Arnim

All images are from performances by the artists appearing at this year’s Culturscapes festival in Basel. Left: Bibata Ibrahim Maïga, Esprit Bavard Performance 2021. below: Tchinatadi Ndjidda, photo: © Jacob Londry Bonkian