When one examines the scientific nature of Anthroposophy, questions inevitably arise. Andreas Heertsch deftly weaves through the affinities and differences one encounters when comparing Anthroposophy as a spiritual science with today’s natural science.

Patzig

As a student, I attended a seminar on Spinoza’s ethics. The 17th-century optical lens grinder was so convinced of mathematics and its clarity that he delineated his ethics like a geometry textbook. In this seminar, the professor – his name was ‹Patzig› of all things and was a proponent of formal logic – asked what an axiom was. Since I had already completed a few semesters of physics and mathematics, I could not resist answering, even as a non-specialist: «An axiom is a sentence that cannot be justified any further, which is evident in itself.» To my surprise, Patzig replied with a smug smile: «Oh, we are well aware that the evidence is one of the things overcome.» Of course, this smile annoyed me, so I replied brusquely: «That can’t be: you wouldn’t talk to me if you didn’t consider what you say to be evident!» Unfortunately, he didn’t feel caught at all: «No, we just believe that what we say is true.» But then he became condescending: «Read Kring’s Handbook of Philosophical Terms – then we will continue to talk!» Meanwhile, I got so angry that I actually bought the Krings. And there you will find under ‹evidence› that this does not belong to the philosophical terms. Franz Brentano, a character revered by Rudolf Steiner, carried out the execution: evidence (precisely that immediate clarity) could not be proven because the proof would have to be evident. But this is forbidden in philosophy as a tautology: I cannot prove something (evidence) that I have already put into the proof (evidence should be evident).

Thus, evidence shows itself as the basis of all intellectual activity: it is the yardstick by which the mind tests its judgments. However, one is not in a position to examine this evidence oneself. Does all knowledge cease with this? Patzig would say here: «Yes, the world is not directly accessible. It’s not even certain that this world I’m talking about really exists. But I believe in it.»

One can only talk about intuition. It can only become evidence through the full participation of the recognizer.

In my anger, I wrote a treatise on how the world becomes real again, first referring to Brentano as the gravedigger of philosophy and then pointing out the simple fact that when I think, I know that I think – and that it would be sick if I doubted it. Perhaps I should have referred to Augustine, who argued against the contemporary skeptics (who were accustomed to questioning everything without further ado) that they could doubt everything but the fact that they doubt.

Patzig returned the tract: The remarks about Brentano were interesting, but the rest was not philosophy, but psychology! Some readers will ask: Why the noise? In fact, this is the real sticking point as to why Anthroposophy is not considered scientific.

What Anthroposophy and (Natural) Science Have in Common

Both sciences are experiential sciences that extend the ordinary experience with the help of certain aids: in the natural sciences, one speaks of measuring instruments, and in Anthroposophy, of supernatural organs. Just as instruments for new measurements (weight, voltage, speed, etc.) are designed with ever greater sensitivity, internal organs always have to be developed with new realms of experience (the living world, mental world, etc.). And just as measuring devices also begin to create chaotic noise with increasing sensitivity (they ‹measure› their self-generated disturbances), internal organs must also be educated so that they remain perceptive, even beyond their own desires and ideas. The results obtained in this way (in Anthroposophy, we speak here of inspirations and imaginations; in the natural sciences of discoveries and models) must be embedded by both sciences in the substance of evidence (called theory in natural science). If this embedding is not yet secured, it is a heuristic in natural science and Anthroposophy: perhaps able to be proven true through life.

Why Anthroposophy as a Science is so Under Attack

Thirty years after this seminar, we are doing a seminar on the perception of formative forces with Dorian Schmidt in the Goetheanum branch. We stand near a cherry tree and are asked to describe our impressions. Friends speak of all sorts of elemental impressions, which they ‹attach› to gestures of the cherry tree. While listening, I can certainly share these impressions, but at the same time, I notice my shaking head: It’s just imagination! Amazingly, Dorian Schmidt encourages these impressions. Since I have to consider him competent in this field because of his phenomenological descriptions of consciousness, suddenly my worldview trained by studying physics gets a slant: And if it were not imagination?

So then – hypothetically: What if these are not imaginations, but formations whose sources I have discredited so far? Immediately the whole litany of objections starts: And how are you sure that you don’t just want to see an elemental being?

Here the scientist in me says, ‹Stop›! Science is the answer to the pre-enlightenment period when superstition and witch burning were ‹scientifically justified›. At that time, all sorts of things were conjured up from the inner realms with well-known, devastating consequences. That can’t be it! In moments like these, scientists open the big drawer labeled ‹spiritualism› and do not want to get involved in any further discussion.

Today I would provoke: Cowards! Instead of disciplining their inner experiences (or, in jargon, ‹uncluttering› and ‹calibrating›), they claim: Only superstition and haunting can come out of this. The problem here is that disciplining takes on a moral character: I should be careful not to make statements about life processes if I fall in love with every beautiful woman (for whose life processes my growing sensitivity becomes more aware) that crosses my path. This kind of discipline is unusual for the scientist because suddenly, one no longer has to create order only in one’s relationship to the (figurative) outside world, but the battlefront is suddenly moved inwards. And there is a whole zoo of weird behavior at home (doppelgangers). Facing this is unpleasant, even frightening, and ignoring these hurdles (guardians of the threshold) quickly leads to social chaos. So I’d rather not! This is not always conscious, which is why all defense systems are ready for battle: This is all imagination – crazy! Scientists are virtually trained to tune their antennae to reality. The development has produced a sense of truth (evidence) in nature: Nature corrects relentlessly – the incorrectly calculated bridge actually collapses.

Why Anthroposophy Overturns Certain Basic Assumptions of Philosophy

The evidence experience described above is referred to by Anthroposophy as intuition. It goes beyond the usual methods of cognition (imagination, inspiration). In intuition, the knower and the recognized become one: In identification, empathy, and unity with the recognized, nothing separates could justify uncertainty.

A simple intuition can take place with one’s own self. You can bring it about through a small exercise: First, you disregard everything that is not (ordinary) self. Then everything you can point to (I’m the pointer) disappears, so everything you have disappears (the difference between habitual and essential). All that remains is my activity that has just been carried out, my direct knowledge that I now experience myself as the one who acts and knows the following experience.

This state of intuition is not limited to the introspection of one’s own self. It can also make itself receptive to the ‹Other.› In contemporary philosophy, this is often referred to as first-person perspective, whereby perspective is only an illustration of intuition. It is capable of the knowledge of essence because it is involved in forming one’s inner self-being based on reality.

The problem with characterizing intuition is that only you can speak about it. You can only talk about intuition, and it can only become evidence through the full participation of the recognizer – which everyone has to do themselves. This is a realization carried out in (waking) will: «Not my will – thy will be done (in my will).»

If this form of knowledge (intuition) is pursued further, research fields arise that remain hidden from the natural sciences. While science – in a sense like the Old Testament: there is a single God – searches for ever more fundamental laws that place the individual in the framework of the general, if necessary with statistics, Anthroposophy can appreciate the individual and thus open up a path to knowledge of essence. Here, less common inspirational methods, such as reading in the book of nature and life, are used in natural sciences.

What distinguishes intuition is the ability to overcome division.

What distinguishes intuition is the ability to overcome division. Thus, it can be understood tp realize the truth. But conventional epistemology is up in arms against this. It lives, as Patzig put it, in the ‹as-if.› This is the price it has to pay if it does not engage with the approach of German idealism (especially Fichte) and allows the first-person perspective as a valid method of cognition. This is where Anthroposophy comes in and further develops this approach. However, it places (rather far-reaching) demands on the recognizers, which, understandably, not everyone wants to face.

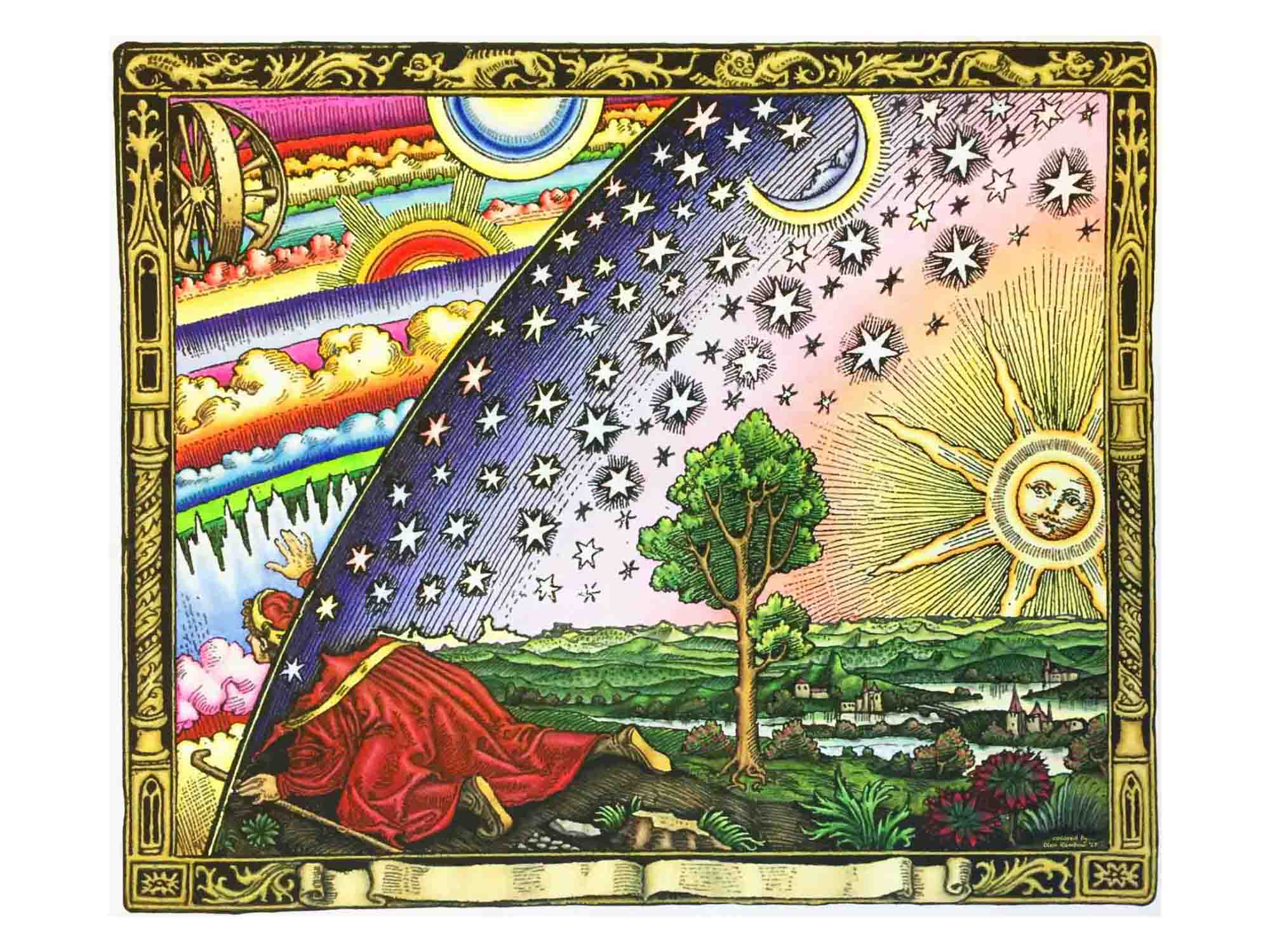

Image Flammarion’s wood engraving or wanderer at the edge of the world, origin unknown, first published in 1888. Colorful modern version. Source: Wikimedia/Houston Physicist, CC BY-SA 4.0. – Translation: Monika Werner