A transdisciplinary colloquium brought the fields of emergency relief work, emergency pedagogy, and trauma pedagogy together at the Goetheanum.

It’s Friday the 13th. June. Hot and humid. I’m already sweating when I join the 27 people gathered this afternoon in the North Hall of the Goetheanum. They’ve come from all over the world for the symposium, “Learning in Difficult Times.” News from Tehran and Tel Aviv arrived this morning: Israel launched a major air strike on Iran; my friends, my family, and my acquaintances are sitting on pins and needles or in air-raid shelters as counterattacks follow. But I sit here—perfectly safe—where the biggest event in the sky is a kite circling above the treetops. As so often when I view the “misery of the world” from this comfortable distance, I feel a powerlessness and fear that weave a tight knot in my stomach.

When I look around, I see a hodgepodge of people alongside a few acquaintances from the Goetheanum. Mostly women of different ages, from various countries, all chatting with each other. I wonder how each person here found their work. How did they become managers, educators, therapists, and peace workers who support children and adults in their communities or in crisis and disaster areas? Do they also feel this knot inside them, or do they approach the world from a different perspective? Could it be precisely because they are all knotted up inside that they approach events in a unique way?

The symposium Learning in Difficult Times is a transdisciplinary forum organized. Participants were invited by four Sections of the Goetheanum: The Pedagogical Section, the Medical Section, the General Anthroposophical Section, and the Section for Inclusive Social Development. In her opening remarks, Constanza Kaliks of the Goetheanum Leadership Team welcomed the representatives of the various approaches and organizations and reminded the audience of the importance of transdisciplinarity and collaboration. This anthroposophical field of work has had many names as it developed over the last two decades: peace education, emergency pedagogy, emergency and disaster relief, and “Essence of Learning.” In this short period of time, so many different people have already had such intense experiences that a diverse spectrum of experts has emerged.

During the two days of the colloquium, the exchange focused on an overarching theme: learning itself. What does it mean for people to learn, and how does learning help children in difficult situations? Constanza Kaliks began her welcome address with an answer to this question: “Learning is an expression of incarnation.” So, what happens to us human beings when learning is weakened, interrupted, or made impossible?

Understanding Resilience

Beatrice Rutishauser Ramm was a Waldorf teacher who received a call from Kosovo during a sabbatical year. She was asked to help set up a kindergarten after the war had ended. Her first assignment was followed by others, and more and more kindergartens were established. She quickly realized that Waldorf education alone was not enough in a chaotic, resource-poor location like Kosovo. In 2004, she quit her job as a teacher, earned a master’s degree in global education, and devoted herself to developing minimum standards for learning and education (Essence of Learning). Her research has inspired new initiatives, some of which have also come to the Goetheanum. For almost twenty years, she has been working as a consultant for large organizations that create learning spaces for children in crisis or disaster situations. This includes, above all, training teachers who need tools to help children regain their ability to learn after experiencing trauma. “Waldorf education is designed for a stable, normal situation. That is the exact opposite of only having the minimum requirements,” she said.

Her core concern is accuracy in assessing situations and the effectiveness of the means used. An acute or traumatic situation, such as she herself experienced in 2005 during a severe earthquake in Pakistan, is something completely different from a chronic crisis, and each situation requires its own specific approach.

Schools are enormously important places for children because they are places of learning and thus represent a future. During her missions, it became increasingly clear that very few of those affected wanted to hear about trauma, especially the children; they didn’t want to feel like victims. But if they were helped to be able to return to the process of learning, children would unfold enormous resilience. When she was in Kosovo, she went to a school that was located next to a new cemetery. She was shocked at first, but then the children told her, “It’s good, Beatrice. This way, we can be with our fathers every day.” For people living in “stable, normal situations,” this may seem unimaginable, but during Beatrice’s keynote speech, it became clear to me that learning itself is an invaluable asset and marker of human health.

Barbara Schiller, Executive Board member and founding member of stART International, spoke the following morning, following on from Beatrice Rutishauser Ramm. Beatrice’s first concept for Waldorf-inspired emergency pedagogy from 2006 already contained the basic principles of much of what defines the field today. That concept included the idea of a “social seed” for children in great need. In view of polycrisis, polarization, and collective powerlessness, this idea has become central to stART International. It’s no longer just a question of “children learning in difficult times,” but rather the social question of “living together in challenging times.” This requires the ability to move together in an unstable environment. The focus is on human dignity. Barbara views her field of work as a training that is becoming increasingly relevant to more people. For this reason, the association makes as much knowledge and educational and therapeutic tools as possible freely available.

In particular, the aspect of “creativity” stood out to me in Barbara’s description. After all, a dignified life has to go beyond basic needs—creativity means feeling an abundance as well as opportunities for development. I see “living” and “learning” as linked together: learning is an active, creative process that I must have the capacity for, but learning itself is the greatest resource for a resilient life.

Jan Göschel, co-leader of the Section for Inclusive Social Development, also addressed the question of resilience. From the perspective of social transformation, he asked what conditions are necessary for resilience and how we should shape a shared future. Other life processes show that resilience is linked to diversity and connectedness on many levels and that resilient systems are always characterized by an abundance, i.e., more than the minimal necessary forces. Without resorting to social romanticism or seeking to gloss over disasters or chronic crises, we can say that it is a sign of resilient human communities that they not only survive challenges but even grow from them.

Can adversity actually reveal certain human capacities that are otherwise overlooked? Are the “social seeds” of the future part of the forces that will break through the established system? Such a thought quickly leads to contradiction, because it can be seen as presumptuous, relativizing, or unsympathetic. But I’m reminded of all the reports from disaster situations where human beings displayed their humanity profoundly. Perhaps these are simply individuals who rise to greatness under pressure, but it also seems to me that they are definitely seeds for the future sense of community. We are probably all aware of the sense of heightened alertness and sensitivity when experiencing a stroke of destiny. It seems to depend on having an inner space. If we have it, we can stay alert. If we don’t, we cannot open ourselves up through the experience of pain—we shut down to protect ourselves.

Encountering Trauma

Melanie Reveriego, chairwoman and principal of the Parzival-Zentrum [Parzival center] in Karlsruhe, reported on the work at her school, where special attention is paid to children and young people who have little “space” to live. She told of an adolescent who sank deeper and deeper into a traumatic vortex and couldn’t find his way out. He later told a judge that the only place where people believed in him was at school. It’s a story that was painful to hear, but it also shows that these are not all stories of miracles. In some cases, people do lose themselves completely, and one good environment among many destructive ones is not enough. Trauma is a social reality, even if we see the effects more clearly in individuals themselves.

Melanie described the fourfold human being, as presented by Rudolf Steiner, and how trauma affects each level: In the physical body, it’s a wound; at the level of the life forces, it can manifest as rhythm and memory disorders, for example; and, in the astral body, as relationship and resonance disorders, lack of impulse control, or depression. In the ‘I’, there comes a lack of strength needed to organize the forces of the other bodies and the soul forces (thinking, feeling, willing), which then leads to a lack of self-efficacy. This is where we need to start. The Parzival Center attaches great importance (among other things) to ensuring that the school is a safe environment, introducing rhythm into daily school life, establishing reliable and trusting relationships, and helping teachers become aware of their inner disposition. This understanding makes Waldorf education an ideal approach for children with special challenges in life.

Philipp Reubke, co-leader of the Pedagogical Section, suggested that the inner disposition of adult caregivers creates a soul environment for children, which has a very strong influence upon them. This was complemented in a conversation with a Ukrainian colleague who reported that it was not only her outward actions that had an effect on the children, but especially her own feelings. She had observed that her anger about the war had a very negative effect on her everyday work as a teacher. If you really want to help children in difficult times, you have to start with yourself. It takes a lot to distance yourself from hysteria and keep yourself together when in shock, so that you can be a source of support for those who are even more in need.

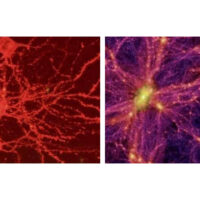

Karin Michael, co-leader of the Medical Section, brought the idea of warmth into the conversation. “Warmth is the element that can penetrate, transform, and bring all the other elements into a flow, to a flexible and fluid state. Warmth loosens hardness and rigidity. Warmth rises upwards, counteracting gravity.” This can be applied to the different levels of the human being and can also be implemented in different ways in education during different stages of development. Most importantly, warmth incarnates; it enables the body, soul, and spirit to be present as an integrated unity within the earthly realm. Trauma arises when this integration disappears. For children who are just beginning their development, trauma can even prevent incarnation. Ultimately, though, all development is healing; every human being is in need of healing; they take a step to develop themselves and thus take a step in healing. This is where the disciplines come together. “Healing” through warmth is a motif common to both anthroposophic medicine and Waldorf education and aims to make future development possible.

Just how shocking life can suddenly be was evident when Ida Oberman and Rosa Balderrama talked about the reGeneration Education initiative. The two women came from California. They founded a project focusing on two schools. Ida reported that it was Rudolf Steiner who brought the ancient motif of “education is healing” back into modern pedagogy. It’s therefore a special moment that this circle has now gathered at the Goetheanum to weave a network for the future. In California, they founded both the Pasadena Waldorf School and the Community School for Creative Education in Oakland. The latter is a place that supports learning for children in difficult life circumstances. The Waldorf School in Pasadena was completely destroyed by the devastating LA fires in January 2025. Rosa, who worked as an emergency educator after the hurricane in Nashville, Tennessee, is now on the receiving end of emergency aid herself. She lost not only her job but also her home in the fire. She was visibly moved when she talked about it. Her colleague Stepha Weinstein was also sitting in the circle; her house burned down, too.

Rosa said that her work as a Waldorf kindergarten teacher helped her; it had all the important elements: movement, rhythm, stories, music. In this day and age, more training is needed for trauma-informed education. It’s immensely important, though, that the adults affected by trauma also experience a sense of community, to grieve together and to feel accepted. The principles of “focus on the whole child, focus on the whole school, focus on the whole community” are therefore central to the two different schools.

Feeling accepted comes from the relationships we build with each other. It’s part of our fragile human nature that we’re social creatures who make life possible for each other, but we can also make it impossible. “To really see the other person is what really heals. Not the methodology,” Stefanie Allon told me during the break. She came from Israel, where she’s worked for decades as a Waldorf kindergarten teacher and teacher trainer with a tireless commitment to peace. What applies to healing also applies to crisis. We are all part of that, too. No one stands outside the world; we are part of the difficulties. Stefanie opened the discussion with an interesting image: the strong Vanya comes to a swamp where the witch Baba Yaga lives. She tries to pull him into the swamp, and a tug-of-war ensues. We are all connected in this tug-of-war with the forces that want to remain in the swamp. It takes a lot, perhaps from this inner struggle with Baba Yaga as well, to emerge upright and courageous like Vanya. Stefanie’s words make it clear to me that it cannot be about the idea of inside and outside, but that a relationship is something much more essential. I am the whole, and the whole is me. The “misery of the world” is my own misery; the abysses we encounter are part of ourselves. Perhaps my perceived “knot” is only the beginning of an umbilical cord to the world.

Finding Each Other

In the concluding round of discussions, Fiona Bay, head of emergency pedagogy for the Friends of Waldorf Education [Freunde der Erziehungskunst], raised an interesting point: anyone who wants to work in emergency pedagogy or in highly traumatic situations must ask themselves, “Why?” What motivates someone to want to throw themselves into these kinds of situations? She talked about how important it is to really live in the moment, to really participate in the world, to respond to a call from contemporary society. But it seems to me that, without being able to elaborate further, she also wanted to say that helpers are a part of what is happening, that they not only need to know themselves well but need to explore their motives for helping. Does the obvious need to want to get involved, to help and support, also need purification?

Peter Selg, co-leader of the General Anthroposophical Section, spoke a few hours before Fiona, shining a light on our inner light by focusing on spiritual training. Esoteric training can only flourish if we change ourselves. Those who only have ideas about spiritual content but don’t change themselves are not able to bring the light to others. One must be able to see one’s own thinking, feel one’s own feelings, and recognize one’s own will, to prevent them from casting shadows. Those who succeed in doing this will do what needs to be done. Inner training purifies thinking and kindles a new fire, a different courage to shape the world. In this way, we can ultimately learn to stand “above the abyss.”

At the end of the gathering, the jigsaw puzzle of contributions formed a clear image in my mind, which, if we take it seriously, can bring a real future to everyone. Through emergencies and chronic crises, this small group is developing an awareness of the interconnectedness of the world, looking at itself and at what is needed in each moment. From the deep impressions of their experiences in this work, everyone in the group has learned about their own susceptibility to crisis and has been strengthened in the art of connecting with one another again and again. This will also enable them to watch over the beacons that every adult will need to navigate in the future. As we become increasingly aware of the complexity of the world, we need more and more space to hold this complicated “inner experience,” and more and more “space holders” who are rich in experience and know how to get there.

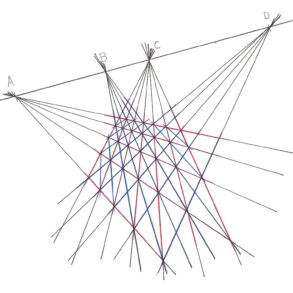

Jorge Schaffer is a member of the Executive Board of International Emergency Pedagogy Without Borders [Notfallpädagogik ohne Grenzen international] in Karlsruhe. He came to the colloquium directly from his assignment following a school shooting in Graz, Austria. He described the participants of the gathering as the trunk of a tree. Their roots are grounded in the transdisciplinary fields of education, therapy, medicine, art, and other related fields. The “nourishment” from this network passes through them—the active participants—reaching the crown, enriching and further developing different fields, right up to the outer tips, where politics and legislators integrate the fruits. The tree is an ecosystem that changes dynamically and interacts constantly. The active participants aren’t isolated from each other; they form a network. Based on this consciousness, I imagine that those gathered together will not only collaborate more but that they could become a resilient “life process”: people who understand and share resilience, diversity, and abundance, like the tree, which isn’t one single thing but many things, which does many things. The deeper its roots, the thicker its branches, the more beneficial the habitat and shade it provides.

Links

- Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE)

- stART International

- Parzival Zentrum

- reGeneration Education

- Friends of Waldorf Education – Emergency Pedagogy (Newsletter subscription on this topic available)

- Notfallpädagogik ohne Grenzen [Emergency pedagogy without borders]

Further training in this field can be requested from stART International or Notfallpädagogik ohne Grenzen [Emergency Education Without Borders]. The emergency education department of the Freunde der Erziehungskunst Rudolf Steiners [Friends of Rudolf Steiner’s art of education] focuses its training on the people affected on the ground.

Recommended reading:

- Bernd Ruf, Educating Traumatized Children. Waldorf Education in Crisis Intervention (Great Barrington, MA: Lindisfarne, 2013).

- stART international, Kinder stärken—Zukunft gestalten. Pädagogisch-therapeutisches Praxisbuch zu Trauma, Widerstandskraft, Kunst und sozialer Beweglichkeit [Empowering children—shaping the future. An educational and therapeutic practical guide to trauma, resilience, art, and social mobility], 3rd edn. (Stuttgart: Verlag Freies Geistesleben, 2023); English forthcoming.

- Friends of Waldorf Education, Trauma Pedagogy: Guidelines for pedagogical first aid (Karlsruhe: Freunde der Erziehungskunst Rudolf Steiners e.V., 2015).

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Title image Initial reception center for refugees, mainly Ukrainian refugees, in Heidelsheim near Bruchsal. Photo: Notfallpädagogik ohne Grenzen