It is more than just a peaceful atmosphere—indeed, something of the essence of peace itself seems to be present at the Goetheanum when Bassam Aramin and Rami Elhanan share their fates and their mission with the 500 people, including many students, in attendance.

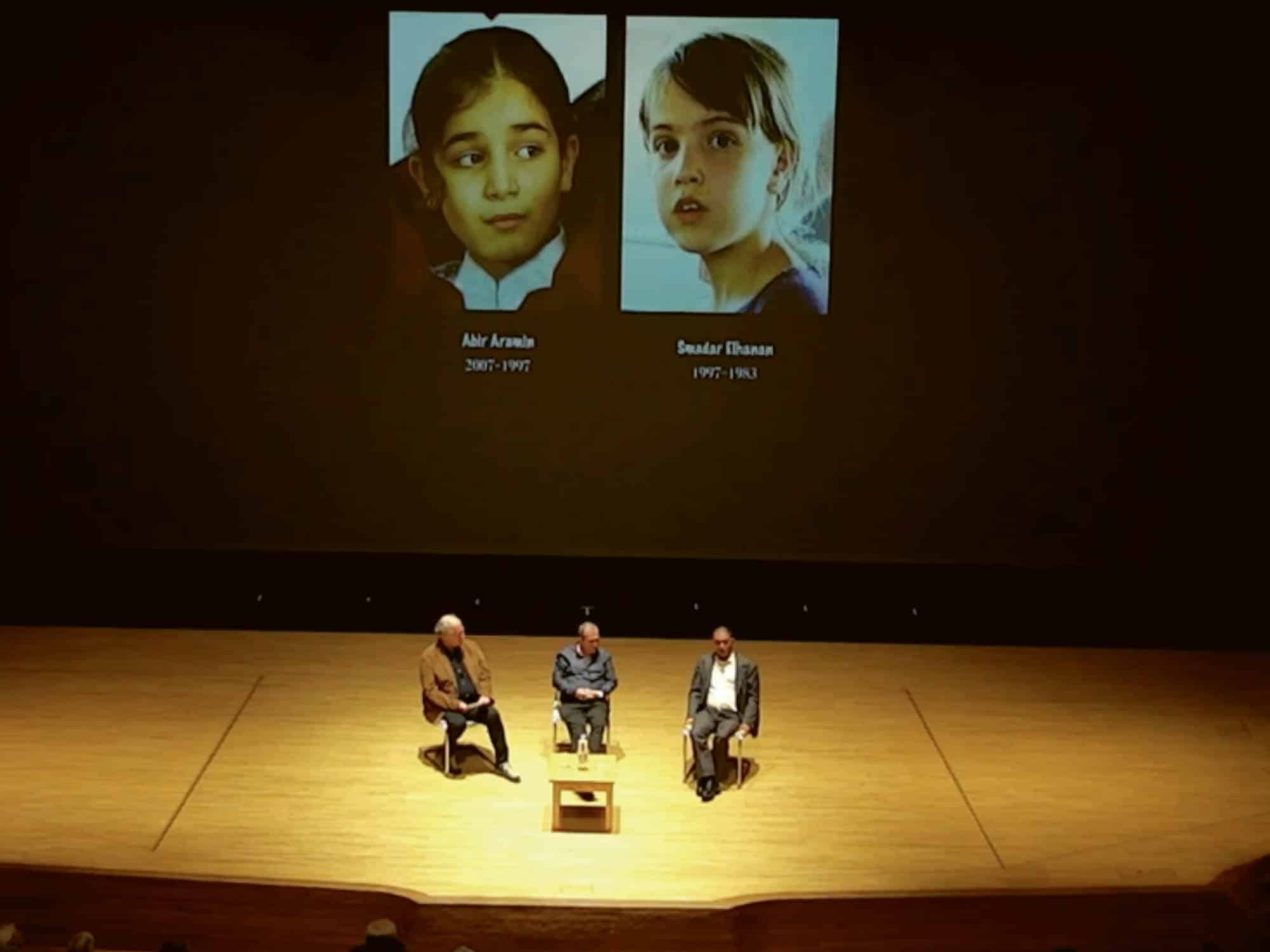

What a picture: two men, friends from opposing warring parties, are sitting on the stage, and behind them, we see the images of Smadar and Abir, their young daughters who were killed in the war—powerless and overpowering. I’m probably not the only one who feels that messages of peace like this have more staying power than revenge or war strategy, or “but-thinking,” as Udi Levy, the evening’s presenter, calls it. The power of this peacefulness is evident to me in the contradictions and the expansiveness that sweeps through the hall. A deeply affected community is formed, and, at the same time, everyone remains in conversation with their own heart and is confronted with themselves. This is what the two men talk about. They talk about the immense pain they felt when they learned of their daughters’ deaths—how that pain permeated their souls and spread over everything and how they coped with it. Their eastern humor pours into the room.

Rami Elhanan, 73, begins by speaking about his parents. His father, a survivor of Auschwitz, was seriously wounded in the war in 1948. The concern of the nurse, who later became his mother, is the reason he is sitting here today. Rami himself fought in three wars: the Yom Kippur War, the Six-Day War, and the Lebanon War. As a tank technician, he had to rescue the wounded from the tanks and witnessed every imaginable kind of suffering. Then, he talks about his daughter, Smadar. She was born in 1983—a dancer, a piano player, a girl everyone called “Princess.” Rami, a graphic designer, and his wife, a professor of education, enjoyed a happy family life in Jerusalem with their daughter and three sons.

On September 4, 1997, a Palestinian assassin blew himself up and killed 32 people. Among them was Rami’s daughter. She had been out with two friends. “It was a Thursday afternoon, the beginning of a long dark night that continues to this day. You felt the blood freezing in your veins, very slowly.” They ran between police stations and hospitals and, finally, to the forensics lab. “Then you begin to grasp that you’re about to see your dead girl. It is a sight you won’t forget for the rest of your life. The family home fills up with thousands of people who sympathize with you. Then you have to wake up and make a decision: What can I do with this unbearable burden on my shoulders, this anger that is beginning to consume me? There are only two options. The first is obvious: you pursue revenge. And that creates the never-ending spiral of violence.”

Pain Unites

Then Rami describes how he learns to explore the other option. “What can make someone so angry, so hopeless, that they are willing to blow themselves up with a 14-year-old little girl?” It took him a year. Then, he met Yitzhak Frankenthal, and that changed his life. Frankenthal’s son Arik was kidnapped and murdered by Hamas in 1994. He subsequently founded an organization in which Israelis and Palestinians who had lost their loved ones could come together. “He simply invited me to attend a meeting. I stood cynically on the sidelines. I never thought that one day I would be one of ‘them:’ people who have lost their loved ones and still stand up for peace. Then I saw something that was completely new to me, to my mind, to my eyes, to my soul. I stood there and saw bereaved Palestinians shaking my hand.” He was ashamed—it was the first time he had seen Palestinians as human beings, not as workers on the street or as terrorists. “I remember seeing an old Arab woman in a traditional black dress, and she was carrying a picture of a six-year-old child, just like my wife was.”

“I can’t really explain what happened to me back then. From that moment until now, I’ve spent my life going everywhere I can, and I talk to everyone—to people who want to listen and to people who don’t want to listen—to convey the simple message that we can change this, once and for all. We can change the endless cycle of violence, revenge, and retribution. The only way to do so is to talk to each other, to experience each other’s pain, and to walk the long road of reconciliation together.”

Rami finds a hundred formulations for this call: there are no shortcuts on this long, bumpy road. But the other way leads nowhere and has a terrible price. He and Bassam are not politicians; they don’t draw maps. Rami says, “We believe that what unites us is our pain. And the pain is caused by the abnormal situation in which one group of people dominates another—the Israeli occupation of the Palestinians—and that must be changed.” He calls pain the ally. “You can use it to bring darkness, destruction, pain, and death on people. And you can use it to bring light and warmth.”

Listening to the Pain of Others

Then Bassam Aramin takes the floor. His story is polar and identical: growing up near Hebron, he and his friends find a weapons cache. His friends throw hand grenades at an Israeli military jeep at night. No one is injured, but the group goes to prison for 14 to 22 years. Bassam was not there, but the investigators learned that he was seen in the village with the group. So, at the age of 17 and totally innocent, he is put behind bars for seven years, beaten and humiliated at a young, vulnerable age. While the other inmates take up arms again straight out of prison, Bassam seeks a different path.

He and his wife, Salva, raise six children in Anata, a small village near Jerusalem. On January 16, 2007, Bassam tells his daughter Abir to be home on time. She leaves defiantly. “She always has to get her own way,” he said to his wife. “She had a strong personality and was very independent. At the checkpoint on the way to my work in Ramallah, I got the worst phone call of my life. It was from the Anata girls’ school. On the other end of the line was Abir’s sister, Areen, calling out Abir’s name. “Abir, Abir!” A friend who was there told me that Abir had been shot in the head by soldiers. I went to the hospital with my wife. We found Abir there. I started to imagine the worst, and that’s what happened.”

Rami stayed awake with Bassam at the bedside. Rami says, “I wondered whether Bassam would keep the strength and courage needed to stay on the path of peace. I thought about how much easier it is to hate, to channel your feelings into violent channels.” You have to listen to the pain of others, Bassam and Rami say in response to the audience’s questions. “You have to discover humanity in yourself, then peace will come.

The next day, there was to be a discussion about whether Rudolf Steiner’s sculpture “The Representative of Humanity” should be put on the stage—here, two representatives of humanity were present.

Excerpted from the event at the Goetheanum on October 15, 2024, Wie aus tiefstem Schmerz Bruderschaft wird [How the deepest pain becomes brotherhood] and the film Sie alle sind unsere Kinder [They are all our children] (2010), Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg, Youtube. Photo screenshot from the recording of the event.

Translation Laura Liska