Did anthroposophical doctors follow, profit from, or oppose the medicine under National Socialism and its “New German Medicine” [Neue Deutsche Heilkunde]? How did the anthroposophical medical profession position itself with regard to the guidelines and consequences of Nazi medicine—from the biological census of the entire population under the dictate of “public health” and maximum performance to the exclusion of Jewish colleagues, forced sterilizations of human beings, and killing of psychiatric patients?

If the anthroposophical medical profession was really part of a civil society resistance movement, as often emphasized by anthroposophists, why, after the ban on the Anthroposophical Society in November 1935, were they still able to continue working in practices, clinics, and individual curative education homes, with anthroposophical medicines at their disposal that Weleda and Rudolf Hauschka continued to produce? Did they belong to the regime—were they ultimately a privileged and cooperative group with ideological convergence, as critics have repeatedly claimed? Leading National Socialists like Otto Ohlendorf, along with their families, liked to receive treatment from anthroposophical practitioners. The well-known anthroposophical pediatrician Wilhelm zur Linden described his politically prominent clientele in a widely circulated autobiography. He was perhaps not the only one whose large practice was popular with high-profile National Socialists (though also with members of the opposition.) Did anthroposophic medicine fit into the National Socialists’ biopolitical concept, with its valorization of the “natural,” the ecological, and the prophylactic? The leading Nazi ideologues wanted stronger immunity, vitality, and resistance, more “health” and “vitality” for the “German people.” Was anthroposophical medicine the suitable form of “biological medicine” for them?

In 2016, these and similar topical and highly charged questions led the Academy of the Society of Anthroposophic Doctors in Germany [Akademie der Gesellschaft Anthroposophischer Ärztinnen und Ärtze in Deutschland, GAÄD] to ask the Ita Wegman Institute to conduct a study on anthroposophic medicine, pharmacy, and curative education during the era of National Socialism, in collaboration with an independent, highly qualified scientific advisory board, the Nazi medical historians Thomas Beddies and Heinz-Peter Schmiedebach, both professors at Charité, The Institute for the History of Medicine and Ethics in Medicine at the Berlin University of Medicine. The first of three volumes with over 900 pages has now been published by the renowned Schwabe publishing house (Basel/Berlin), the oldest scientific publishing house in the world (founded in 1488 as Offizin Petri [Office of Petri]). This first volume covers the relationship between anthroposophy and National Socialism (and vice versa) as well as the activities of anthroposophical medical professionals from 1933 to 1945. Volumes two and three will be published by Schwabe in 2025 on Weleda and Wala (vol. 2) and on anthroposophical psychiatry and curative education (vol. 3).

618 Medical Practitioners

Would we have accepted and taken on the task if we had been conscious in 2016 of the mountain of work we were embarking on? Hardly. The uphill climb began with the question: who was an “anthroposophical doctor” between 1933 and 1945? Who can be described as one, and whose behavior should we now describe? What is an anthroposophical doctor? The question is still not easy to answer today, and simply prescribing Weleda or Wala remedies is probably not enough to qualify as such. Unlike today, between 1933 and 1945, there was no defined training curriculum and no certificates, and there was nothing to refer to or define a specific group. “Anthroposophic doctors” were not a category in the Reich’s medical index, medical card file, or medical register. The name did not appear on descriptions of practices or letters (which, politically speaking, was a good thing since it provided protection and concealment). There was, however, a Weleda card file with nearly 4,000 interested doctors, but it must be considered lost. Still, the “interested” doctors were certainly not all anthroposophists or representatives of the medicine conceptualized by Rudolf Steiner and Ita Wegman in terms of anthroposophy and therapeutic ethics. In the end, we found a total of sixteen lists of doctors in the Ita Wegman archive and the Weleda archive, with many notable but also unknown names, many of them women. We examined them with regard to their affiliations with the Anthroposophical Society and the Medical Section at the Goetheanum, the medical department of the School of Spiritual Science in Dornach. We found 211 people who were members of both organizations, while 176 doctors were only affiliated with the Anthroposophical Society.

We considered both groups together, i.e., 387 people, to be the core group of the anthroposophical medical profession. In addition, we found 231 doctors who were demonstrably proactive in promoting anthroposophic medicine between 1933 and 1945 but who had no institutional affiliation. We refer to them as the extended group. Together, therefore, we were dealing with 618 persons, 387 of whom were active in Germany during the period in question, plus 149 in countries occupied by Germany (from 1938). We investigated this group of people according to, among other things, specialist qualifications, income, further professional trainings, and publications on anthroposophic medicine; we searched for offices and clinics, for any trace in local archives, in the records of the “denazification” tribunal [Spruchkammer] after 1945, in the Federal Archives [Bundesarchiv], in many archives, everywhere. We also researched their memberships in Nazi organizations.

What Ita Wegman Foresaw

Moreover, we weren’t only concerned with the many individuals but also with their associations, including their health policies. On October 7, 1933, the Deutsches Ärzteblatt [German Doctors’ Sheet] and several other journals published an appeal to the “biological doctors” by the Reich Doctors’ Leader (Reichsärzteführer) Gerhard Wagner, the chief medical officer. Wagner claimed to want to unite doctors working with natural remedies in order to, after methodical examination, finally give non-conventional medical procedures the status they deserved in the medical landscape.

The question of whether to form an association and register with Wagner was the subject of intense and controversial debate within the anthroposophical medical profession. The Freiburg psychiatrist and clinic director Friedrich Husemann (the Wiesneck Sanatorium is now the Friedrich-Husemann-Klinik, in Germany) was unconditionally for it; Ita Wegman was radically against it. She foresaw the “synchronization” [Gleichschaltung, totalitarian coordination of all areas of German Society, i.e., Nazification], the Nazi acquisition and instrumentalization of the anthroposophical medical association. Husemann, on the other hand, hoped for greater societal recognition and effectivity—an overcoming of their isolation.

Subsequently, no more than 45 colleagues joined the association founded by Husemann, and in 1935, they became part of the Reich Working Group for a New German Medicine [Reichsarbeitsgemeinschaft für eine Neue Deutsche Heilkunde] under Gerhard Wagner. Contrary to what some critics have claimed, they played a marginal role in it, or none at all—they held back from conference contributions, publications, and influence. Also, the Reich Working Group did not exist very long, partly because the “Four Year Plan” under Hitler/Göring in 1936 was aimed at war capability and relied on the high performance of conventional medicine and the efficiency of “German documentary research” [Tatsachenforschung, i.e., research on factual cases; policy “in action.”]

Nevertheless, the internal discussions of the association, as reflected in the correspondence we found, are significant. Many of the anthroposophical doctors disagreed or quietly refused—they didn’t want to be given a status defined as a “biological” outsider group close to the regime and “folk medicine” [Volksheilkunde], they didn’t want separation from “orthodox medicine,” and did not want to accept the clause concerning Aryanism. According to its self-image, the anthroposophical medical profession was something different. It did not stand solely for “biological natural remedies,” but for a spiritual-scientific extension of medicine, and, thereby, also for humanistic medical ethics and individual patient treatment (instead of “bodies of peoples/folk” [Volkskörpers]); it stood against eugenics and selection. Friedrich Husemann also saw it this way—but, in 1933, he was still favorable towards Wagner, only soon to be proven wrong, not least by the difficult destiny of his patients in the “biopolitical” state.

Systematic Separation of Anthroposophy

Through various internal correspondences, it has also become clear that many anthroposophical doctors (soon to include Husemann) had reservations about the supposedly “successful model” of biodynamic agriculture under Erhard Bartsch and his Reich Association for Biodynamic Agriculture and Horticulture [Reichsverband für biologisch-dynamische Wirtschaftsweise in Landwirtschaft und Gartenbau] including his “model farm” Marienhöhe near Bad Saarow.1 Under heavy pressure and on the verge of being banned, Bartsch and a few colleagues set about building up a network of political contacts in order to show what Demeter agriculture could mean to the “new Germany.” Well-known ministers visited his farm, and questionable liaisons developed. From 1940, the SS [Schutzstaffel, “Protection Squad,” Nazi paramilitary organization] under Himmler was interested in introducing biodynamic methods to the SS experimental farms, only with a systematic separation of anthroposophy, which was considered hostile to the state. As the biodynamic methods operated without artificial fertilizers, they seemed to Himmler to be particularly suitable for the new “living space in the East” [Lebensraum im Osten, a policy of expanding into Eastern Europe, annexing land and resources for Germany]. This is how the practices of a new form of agriculture came to the German Research Institute for Nutrition and Food [DVA, Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Ernährung und Verpflegung], including the SS medicinal herb farm at the Dachau concentration camp, the largest in Europe, with 1,000 prisoners as forced laborers and a large botanical research area.

The psychiatrist and psychotherapist Husemann, the leading head of the anthroposophical medical profession in Germany, was critical of this politicization and instrumentalization—apparently becoming more critical from year to year. His three books published during the Nazi era: Goethe and the Art of Healing: Observations on the Crisis in Medicine (1936), On the image and meaning of death: outline of a spiritual-scientifically oriented history, physiology, and psychology of the problem of death (1938, not published in English), The Image of the Human Being as the Basis of the Art of Healing: Sketch of a spiritual-scientifically oriented medicine (1941)2 are beholden only to themselves. They did not adapt to Nazi medicine, neither ideologically nor terminologically, were uncompromising and without concessions, and were the actual textbooks of anthroposophical medicine at that time. We found the same ideological continuity of topics and concerns when we analyzed the medical professional resources, including the Weleda-Nachrichten [Weleda News] (with a circulation of up to 80,000 copies) and the anthroposophical drug assessments. This does not mean, however, that all anthroposophical physicians kept a distance from Nazi organizations (though Husemann did—he did not have a single membership). Around 10% joined the NSDAP [Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, National Socialist German Workers’ Party, the Nazi party] for various reasons (compared to the nearly 40% in the mainstream German medical profession), 6.2% joined the SA [Sturmabteilung, “Storm Troopers,” Nazi paramilitary organization superseded by the SS] (compared to 26%), and 2.5% joined the SS (compared to 7.2%).

Contrary to the Idea of Völker [Peoples]

With very few exceptions, those who joined these organizations did not take on official positions or leadership roles. If their anthroposophical orientation was known, they had no chance of doing so, and after the Anthroposophical Society was banned by Reinhard Heydrich in November 1935, most of them were no longer accepted. According to National Socialism, the “international position,” the “relations with foreign Jews,” “pacifists,” “Freemasons,” and the “individualistic education” were all contrary to the idea of Völker [peoples, lit. “folk”; a collective unit based on culture and/or race], and were considered “hostile to the state” and “dangerous to the state,” as written in the official ban of the Society. This was and remained the unambiguous vote of all SS Security Service [SD, Sicherheitsdienst, security department in charge of foreign and domestic intelligence and espionage] appraisals until 1941 when almost all anthroposophy-oriented institutions that were recognizable as such were closed.3

In May 1936, a Security Service report stated: “Anthroposophy detaches the spirit from its connection with the race [Rasse] and the people [Volk] and condemns what pertains to race and folk to a lower sphere of primitiveness, to instinct, to the drive which is to be overcome by the spirit, to a prehistoric time. Thereby, it proves its entanglement with the main currents of European intellectual history to date, above all the Enlightenment, German idealism, and liberalism of the past centuries.”4 In 1941, a report by the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA, Reichssicherheitshauptamt) stated: “If the totality of ideological thought and its effect on the overall opinion and attitude of human beings is to be accepted, it cannot be doubted that the adherent of anthroposophy must inevitably become an opponent of National Socialism, or at least remain alien to National Socialism.”5

Steiner’s writings were banned as early as 1935, anthroposophical working communities were searched, libraries confiscated, and people interrogated and arrested. The Burghalde Sanatorium near Bad Liebenzell had been closely monitored since its opening in 1935 to see whether it was possibly anthroposophically oriented. In 1941, it was explicitly forbidden to admit anthroposophically oriented patients or to employ nurses thus trained. The popular general practitioner Hermann Keiner from Dortmund, a pioneer of anthroposophic medicine in the Ruhr region with a constantly overcrowded waiting room (“if no one [keiner] heals you, Keiner heals you”), was involved in a total of six lawsuits, was imprisoned under harsh conditions, and lost his library, all his papers, and his health. He refused to accept Nazi medicine and its dictates, stood up for anthroposophy and his medical-therapeutic convictions, and was punished for it. Anthroposophical medicine as such was never up for discussion in the Nazi state; its anthroposophical premises and ethical objectives were out of the question. If anthroposophical doctors were able to continue working, it was because they were not declared as such and were not known to the authorities.

The approach taken by the Gestapo and the SS against anthroposophy itself was resolute. In the polycratic system of the Nazi regime, however, there were always individual authorities and representatives of authorities who protected anthroposophical institutions on the basis of personal interests or in an attempt to make their methods benefit the Nazi state. For example, Alfred Baeumler, professor of political education in Berlin and co-worker in the Rosenberg Office [Alfred Rosenberg’s Reich surveillance office], famously supported the didactics of Waldorf schools—“without anthroposophy”; Rudolf Hess supported biodynamic agriculture, among others, and Otto Ohlendorf’s pharmaceutical support included Rudolf Hauschka and Weleda. The circumstances under which the psychiatric clinic Wiesneck Sanatorium survived and its endangered patients were not taken away (as well as the anthroposophical curative education homes) have not yet been fully clarified. Compared to Emmendingen and Bethel, these were small, private places without any organized association; psychiatrists from all over Germany sent their patients to Wiesneck, including famous university clinicians and professors. Wiesneck was considered a comparatively safe place with a high therapeutic ethos.

A Handful of Professed National Socialists

In its final part, our study moves on to individual portraits of the followers, conformists, and collaborators, but also of those who resisted within the anthroposophical medical profession, each with increasing intensity. There were some self-professed National Socialists in the core group—a handful, perhaps, only three or four: Jaap Sierts Galjart in the Netherlands; Fritz, Sigmund, and Hanns Rascher in Germany. As the documents show, their path brought considerable alienation from the rest of the profession. The fact that Galjart collaborated with the Nazi occupying power and its Nazi health policy in the Netherlands and was actively involved in it came as a shock to his colleagues and was the major exception. Why he did it remained a mystery to everyone.

Admittedly, there were gray zones (in the sense of Primo Levi)6 in the core group and beyond. The anthroposophist Walter Pfabel, as head of the Reinickendorf health department, was also an assessor in the Berlin Hereditary Health Court [Erbgesundheitsgericht, jurisdiction over the sterilization law]; the company doctor Walter Martin supported efficient performance medicine [i.e., optimization of well-being for specific tasks] at an Austrian coal mine with the help of Weleda products, within the ideology of the German Labor Front [DAF, Deutschen Arbeitsfront, labor organization of the Nazi Party]. The extent to which he was really involved with anthroposophy or only prescribed Weleda remedies remains an open question. Martin had previously been imprisoned in Buchenwald, which does not excuse him in any way, but he may have tried to escape condemnation by proving his loyalty.

Hanns Rascher, from Munich, was the only anthroposophical doctor who collaborated with the SS Security Service and advocated the compatibility of anthroposophy with National Socialism. He was mentally unstable, prone to delusions of grandeur, wanted to become the Reich Doctors’ Leader [Reichsärzteführer], and was always in need of money. In the end, he became famous through his son Sigmund, who made a career in the SS under Himmler as an extremely brutal, experimental SS doctor in the Dachau concentration camp.

For a long time, it was said in anthroposophical literature that Sigmund Rascher was only a transient and difficult Waldorf student with no closer connection to anthroposophy. However, he did know anthroposophy and was wholly surrounded by an anthroposophical social circle. Both his parents were anthroposophists, as were both his siblings. The family owned a house in Dornach next to the Speisehaus [local canteen/restaurant down the hill from the Goetheanum], and Sigmund worked for a time at the Scientific Research Institute at the Goetheanum in the Glashaus (1933/34), became a member of the Anthroposophical Society, and a master student of Ehrenfried Pfeiffer in the technique of so-called “sensitive crystallization,” about which he contributed two publications in the prestigious Münchner Medizinische Wochenschrift [MMW, Munich Medical Weekly], in 1936 and 1939. He did not work as a practicing anthroposophical doctor (like his father, though he sometimes stood in for him in his practice) but rather saw himself as a scientist. He finally made his “career” in Dachau, in the perversion of medicine, as head of a “military science” research group of the SS Ancestral Heritage [Ahnenerbe] organization, in the dynamics of killing, with cruel high pressure and hypothermia experiments on defenseless prisoners, many of whom died an agonizing death. He reported his father (his anthroposophical relationships and trips to Dornach) to the police and had him temporarily detained—possibly to prove his own distance from anthroposophy.

Anthroposophical ideas did not guide Sigmund Rascher’s actions; quite the opposite. He proved, however, just how far one can fall despite meeting anthroposophy—and even the suicidal hydrocyanic acid capsules used by the SS can most likely be traced back to his activities in Dachau. Quite a few of the anthroposophical doctors knew the Rascher family and Sigmund Rascher’s MMW publications; they were shocked to read about his Dachau experiments and the whole abyss in the first Nuremberg trial report by Alexander Mitscherlich and Fred Mielke in 1947. “One of us?”

The Resistance

Yet, we also provide portraits of doctors and anthroposophically-oriented medical students who were active in the resistance, starting with Josef Kalkhof, the indomitable general practitioner in Freiburg, and the Cramer-Oppen medical couple in Heidelberg, who worked intensively, and at their own risk, for Jewish patients under threat. Trude Förster protested against the “Aktion T4,” the killing of psychiatrically ill human beings. Henny van Suchtelen, in the Netherlands, refused to comply with Nazi medical policy and was sent to prison. Through oppositional literature, Felix Auler gathered a circle of pupils and students around himself. And the anthroposophical doctor Rolf Brestowsky supported a communist resistance group in Düsseldorf. There were others.

Ita Wegman, Rudolf Steiner’s closest medical colleague, lived the resistance out of anthroposophical conviction in an exemplary manner—in her clear and early awareness concerning the Nazi regime and its totalitarian character, in the escape aid she provided for Jewish colleagues and others in danger, in her approach against the application of the Sterilization Act in curative education, etc. She radically rejected National Socialism, racism, and anti-Semitism. As early as April 17, 1933, she wrote in a letter to D. N. Dunlop, the head of the British Weleda: “It will now probably be the case in Germany that freedom will no longer prevail there and perhaps commissariats will be appointed everywhere to determine things, both in political life and in spiritual life, such as the administration of schools and other things, as well as that all Jews will be put out. That is naturally our first concern now, the various friends who cannot now remain in Germany, whether because they are of Jewish origin or because they are not completely safe in Germany due to certain work that has taken place more in the social field.” On July 18, 1933, she said: “It is shocking how [in Germany] you have to discard all individuality and become absorbed in the state and how everything revolves around National Socialism.”

We also describe the commitment of the anthroposophically-oriented medical student Traute Lafrenz (Page), who, as a friend of Hans and Sophie Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, and Christoph Probst, was part of the closest core of the White Rose [Weißen Rose] resistance group and distributed leaflets inspired by Rudolf Steiner’s Philosophy of Freedom and Husemann’s book Das Bild des Menschen [The Image of the Human Being]. Having escaped the death sentence of the People’s Court [Volksgerichtshofes, jurisdiction over all crimes of treason] under Roland Freisler at the end of the war, she went to the USA, worked as an anthroposophical doctor, and ran the Esperanza day care center and school in Chicago, primarily for children and young people from poor immigrant families in need of spiritual care.

Lastly, we researched and portrayed the paths of the (according to Nazi terminology) 29 “fully Jewish” colleagues in the anthroposophical medical profession (three, at least, had Jewish grandparents); almost all of them were in correspondence with Ita Wegman. They did not experience any marginalization in the anthroposophical medical profession; quite the opposite. 24 of them were able to flee Germany, often with the support of colleagues, including the 17 Germans in the group. The Berlin anthroposophical doctor Ilse Rennefeld was saved with the help of the resistance circle around Wilhelm Canaris, Hans Oster, and Hans von Dohnanyi and was able to reach Switzerland. Eva Canaris, a daughter of Admiral Canaris, was treated in anthroposophical healing centers and, at times, by Friedrich Husemann.

We have, however, also discovered that two anthroposophical doctors, one of Jewish origin, were murdered in German concentration camps: the Ukrainian doctor Henriette Ginda Fridkin (from Kharkiv) in Auschwitz-Birkenau on February 11, 1943, who had cared for the sick collaborators during the construction period of the First Goetheanum in Dornach, and the Prague doctor Erich Knapp, who arrived at the same place on October 23, 1944 on a transport from the Theresienstadt Ghetto [in German-occupied Czechoslovakia]. The reports on his therapeutic work in Theresienstadt are impressive. They can be read in the writings of survivor Helen Lewis (formerly Helene Herrmann) in A Time to Speak (Newtownards, UK: Blackstaff, 2010).

On the Spirit of Humanity

Thus, the study also became a search for specific individual human beings, their activities and life paths, and their motivations and destinies in difficult historical times. Were the anthroposophical doctors aware of the abyss of Nazi medicine, of the totality of selection and killing? Those working in psychiatry and curative education certainly were—we not only found relevant correspondence but also evidence of protective measures, at least for the children, adolescents, and adults entrusted to their care. Ita Wegman was not surprised by the dynamics of the destruction, as her legacy shows, but she was surprised by its extent.

Rudolf Steiner had already warned urgently after the First International Eugenics Congress (July 1912, organized by the British Eugenics Education Society) of the societal consequences of social Darwinist, eugenic, and “racial hygiene” concepts, including the instrumentalization of medicine for state and economic purposes. In 1920, he read the book by Professors Binding and Hoche, who called for Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life.7 “And the first half of this century will hardly come to an end without something terrible happening in these fields,” he said in Berlin on March 27, 1917.8 He was no Nostradamus, but he saw the trends and forces of development. He was aware of the “dictate of contempt for humanity” that Mitscherlich and Mielke spoke of in 1947. “It is . . . a matter of making the whole human being present in medicine”—Steiner would certainly have signed off on this sentence by Alexander Mitscherlich (1948).9

The comparatively small group of anthroposophical doctors were only able to oppose the catastrophic developments between 1933 and 1945 to a very limited extent. Nevertheless, the 1,500 surviving patient files from the Wiesneck Sanatorium during the same period sound a clear message, as do the reports from anthroposophical curative education. They bear witness to the spirit of a different medicine and humanity. Still, by no means were all anthroposophical doctors in the resistance—and the spectrum between Ita Wegman and Traute Lafrenz on the one hand and Sigmund Rascher on the other was vast, in person and deeds, judgments, and morality. “As long as a teaching remains just a teaching, no difficulties arise,” wrote Ita Wegman on January 16, 1935, in one of her astute letters.10 Living the teaching of the Study of Man in the time of its total obscuration is challenging.11

Presentation

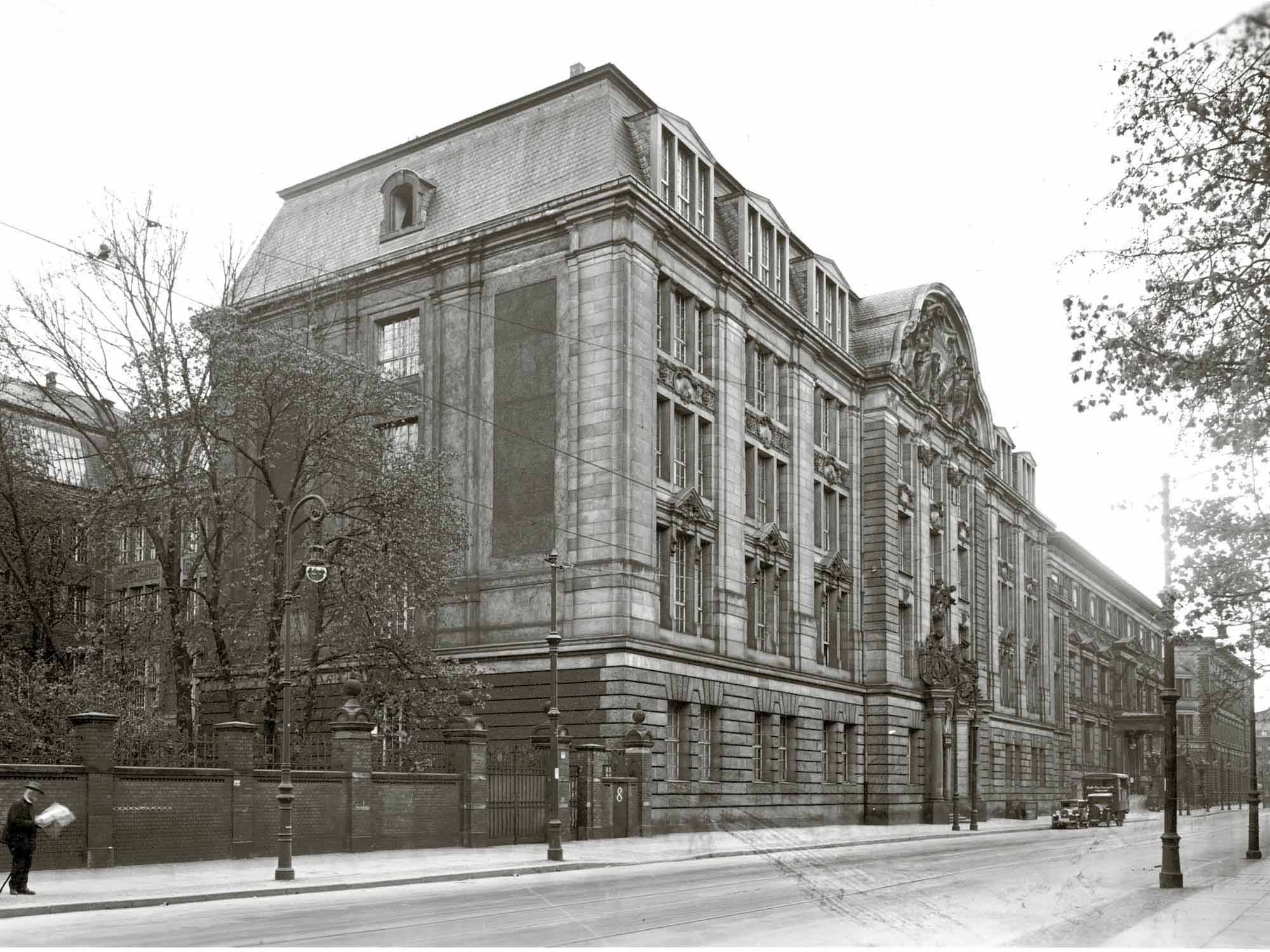

The first volume of our study was presented to the press, along with a scientific panel, on May 23, 2024, in Berlin in the medical history lecture hall of the Charité, Rudolf Virchow’s old place of work.

Book Peter Selg, Susanne H. Gross, Matthias Mochner, Antroposophie und Nationalsozialismus: Die anthroposophische Ärzteschaft [Anthroposophy and National Socialism. The anthroposophical medical profession] (Basel: Schwabe, 2024).

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Title image Secret State Police Office (later Reich Security Main Office), 1933, Berlin, Prinz-Albrecht-Straße 8. Source: Federal Archives.

Footnotes

- Cf. Jens Ebert, Susanne zur Nieden, and Meggi Pieschel, Die biodynamische Bewegung und Demeter in der NS-Zeit: Akteure, Verbindungen, Haltungen [The biodynamic movement and Demeter during the time of National Socialism: participants, connections, and approaches]. (Berlin: Metropol-Verlag, 2024); see also Demeter, Biodynamic Federation Demeter International, Section for Agriculture, “The Biodynamic Movement and Demeter in the Time of National Socialism,” Goetheanum Weekly (October 31, 2024); Marienhöhe farm continues to exist today and is claimed as the oldest biodynamic farm in Germany (since 1928), see Hof Marienhöhe.

- Friedrich Husemann, Goethe und die Heilkunst: Betrachtungen zur Krise in der Medizin (Dornach: Philosophisch-Anthroposophischer Verlag, 1936), published in English as Goethe and the Art of Healing: A Commentary on the Crisis in Medicine (London: Rudolf Steiner Publishing, 1938); Vom Bild und Sinn des Todes: Entwurf einer geisteswissenschaftlich orientierten Geschichte, Physiologie, und Psychologie des Todesproblems [On the image and meaning of death: a sketch of a spiritual-scientifically oriented history, physiology, and psychology of the problem of death] (1938), not yet available in English; Das Bild des Menschen als Grundlage der Heilkunst: Entwurf einer geisteswissenschaftlich orientierten Medizin [The image of the human being as the basis of the art of healing: a sketch of a spiritual-scientifically oriented medicine] (1941), published (in part) in English as The Anthroposophical Approach to Medicine. Vol. 1: An Outline of a Spiritual Scientifically Oriented Medicine (Hudson, NY: SteinerBooks, 1983, rev.).

- Cf. U. Werner, Anthroposophen in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (1933–1945) [Anthroposophists in the time of National Socialism] (Munich: R. Oldenbourg, 1999).

- P. Selg, S. H. Gross, M. Mochner, Anthroposophie und Nationalsozialismus. Die anthroposophische Ärzteschaft [Anthroposophy and National Socialism. The anthroposophical medical profession] (Basel: Schwabe, 2024), p. 304.

- Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter-Partei. Schutzstaffel. Reichssicherheitshauptamt [National Socialist German Workers’ Part. Protection Squad. Reich Security Main Office], Die Anthroposophie und ihre Zweckverbände: Bericht ünter Verwendung von Ergebnissen der Aktion gegen Geheimlehren und sogenannte Geheimwissenschaften vom 5. Juni 1941 [Anthroposophy and its special-purpose associations: report using the results of the action against secret doctrines and so-called secret sciences of June 5, 1941] (Berlin: Reichssicherheitshauptamt, 1941).

- Primo Levi, “The Gray Zone,” in The Drowned and the Saved (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017); originally published in Italian in 1986.

- Karl Binding and Alfred Hoche, Allowing the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Life: Its Measure and Form (Greenwood, WI: Suzeteo Enterprises, 2012).

- Rudolf Steiner, Building Stones for an Understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha: Human Life in a Cosmic Context, CW 175 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2015), lecture in Berlin on March 27, 1917.

- Alexander Mitscherlich, Gesammelte Schriften [Collected Writings], vol. 7 (Frankfurt a. M.: Suhrkamp, 1983), p. 426.

- To Franz Löffler on January 16, 1935, Ita Wegman Archive, Arlesheim, Switzerland.

- Rudolf Steiner, Study of Man: General Education Course, CW 293 (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 1995), “The First Waldorf Teacher’s Course,” in Stuttgart from Aug. 20–Sep. 5, 1919.