A plant transplanted from one bioregion to another area remains the same species, but its expression embodies its new environment. Therefore, the importance of diversity in the method underlies the production of biodynamic preparations and raises the question of what constitutes identity.

The soil is the last thing that happens, but in agriculture, it’s what we begin with. We begin with what is sense-perceptible, but what is initially obvious to the senses is a final product, like our nails and our skin—something that falls out of the living world and has crystallized into form.

At the Josephine Porter Institute, we make biodynamic preparations for most of North America and ship them around the world. But these are preparations that are made in one part of the country with a particular microbiome and a particular soil. That’s a perplexing dilemma. The environment moves into the preparations—every preparation has a signature of that land, that climate, and no two preparations will be quite the same. When I dig out horns—and at the Josephine Porter Institute, we buried about 5,000 horns last year—there’s an enormous difference in the content from horn to horn. If it is truly living, truly biodynamic, it must look different in each location because this is not a factory—we’re not copying and pasting. I’m a big proponent for people making their own preparations in their own bioregion, as much as possible. That is part of the impulse at the Josephine Porter Institute: we’re looking to decentralize preparation production, and we have regional groups working in this way.

Enhancing the Spiral of Evolutionary Development

So, we begin with substance in the soil that has a formless quality. Steiner says: “Chaos is, at the same time, the essential reason of the constant and ever present fertility in nature. …. And unless at some time or other you mingle chaos with the cosmos, further evolution is never possible.” That is the kind of chaos we want to restore into the soil. We can think of it as potential energy. Unless the soil has a reserve of formless potential, the plants cannot express themselves well. And the shape of that formlessness is different in each location—there’s a different potentiality in each place.

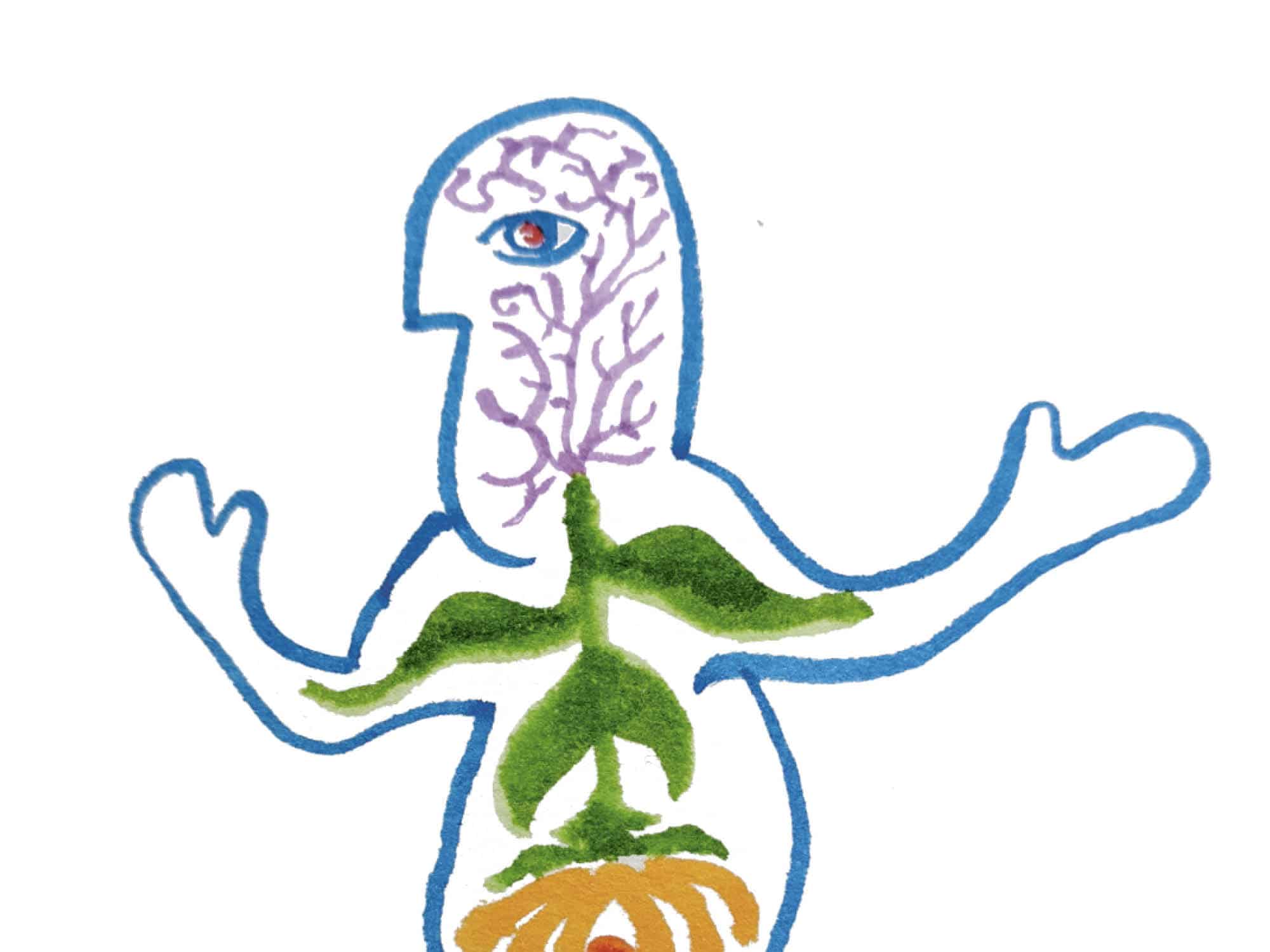

Everything that streams in from the cosmos streams back out, but by a slightly different route. Every plant is sort of a throttling, a limiting, and a re-directing back to the cosmos. It never returns in the same form. If it were just to go out to the cosmos and then return, we would just end up with dead repetition and no particular development. But because it returns and changes, we end up with an expanding spiral of development. This is evolution. It happens every time that I bury preparations on the farm because the soil was treated, the cows ate the grass that has been treated—the nutrient density of the grass is better, the cows are healthier—I collect that manure, and it all becomes a building bioreactor of fertility.

For the silica preparation, made with quartz, I offer a quote from John Ruskin: “A flower is to the vegetable substance what a crystal is to the mineral.” From the chaotic, formless world of dust, we get something crystalline that is transparent to light. Steiner says: “In crystals, we find the transition of the formless mineral world to the living capacity of the plant kingdom to produce forms.” For me, most of the preparations have a floral impulse: they belong with the metabolic bud of the human being. We collect flowers, which are full of aromatic oils that would like to diffuse—these oils are light, they’re volatile, and they like to go back to the cosmos. How do we get that into the soil? Well, we have to settle it down, contain it, and introduce it to the root. We take this reproductive quality, this libidinous floral impulse, and introduce it to the head of the plant. We contain the outward diffusing energy and bring it down to the root, which then helps the upward cosmic stream and makes proud, beautifully colored plants. So we collect Yarrow flowers, something that never produces a sweet, edible fruit the way that an apple or a plum does, we contain it in a suitable sheath, and allow it to ripen. We hang it in the sunlight, but it’s sunlight only half of every day, so it’s actually a rhythmic warming and then cooling—a breathing process that is imbued into each preparation that we hang.

The Importance of a Rich Context

On our farm, we always intersperse aromatic herbs alongside everything else just to have that context. Having pollinator plants near your plants helps enhance the astrality around them. However, it’s not just the aromatic quality but the fact that pollinators, bees, butterflies, and everything else that is flying around are dynamizing the air. It’s like drying herbs: if we put them in a dark room, they will dry. But if we put a gentle fan breeze on them, they will dry in a more auspicious way. If we watch all the lines of force as bees and insects are swarming around the garden, we see they are causing the air to move in ways that it would not by itself.

Each biodynamic preparation sheath is selected as an animal membrane, or an astral context, that contains the process that each specific herb is intended to influence. I like to grow the herbs and use the membranes from animals on the same farm, so they all belong together. I find that even when I eat food from my farm, from my garden, I need less of it because it resonates. When I eat food from all across the globe, it introduces an element of chaos. The principle that I’ve experienced within my own body, I believe, applies also to the preparations.

It’s not a dogma, saying we can only use a particular species. It’s a question: how can we get as close to the ideal as possible in each given situation? We have to think about the geology, the history, the kind of plants and what they overcame in a given climate, and the adaptivity and health of the animal. And those stack together in making that unique preparation. Then we have to consider the effect of the human being doing the work, which further complicates it to a point that we can ask if any two preparations are really the same species anymore. If we, as individuals, are our own genus and species, then the work that we’re doing, the creative work involved is also something of that magnitude. I hope what I’ve done today is complicate the image enough that we feel a little more how different these preparations are when made, even to very high standard in distinct locations, and how much that brings into play. Thank you.

This is a shortened and lightly edited version of the talk given at the conference.

More Natural Science Section: Evolving Science 2024 | Perennial Roots Farm | Josephine Porter Institute

Images Drawings by Stewart Lundy