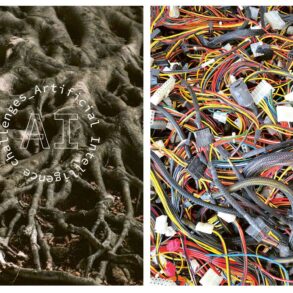

Microbes were on Earth for three billion years before any other living creature appeared. As Florianne Koechlin puts it, they invented almost everything that constitutes life. Microbes connect cells, internal metabolism, soil with plants, plants with animals, and everything with us.

Plants choose which microbes they take into their root area and which they don’t. They keep harmful pathogens out and let others in. They do all this using “aromas” to communicate with their soil microbiome. Microbes also communicate with each other. About a third of all of a bacterium’s genes are there for communication. So, even for the smallest creatures, communication is the foundation of life. Beneath our superficial differences, “We are all of us walking communities of bacteria. The world shimmers, a pointillist landscape made of tiny living beings,” said Lynn Margulis, the great biologist who helped develop the Gaia hypothesis. We are all an interlocking ecosystem, and together, we form a huge metaorganism for which Margulis coined the term holobiont. And at the beginning, there are the microbes. We host the microbes, or rather, the microbes host us. Until now we thought that humans have a gut microbiome and plants have a root microbiome. The new way of thinking is: my bacteria, my microbiome and I have evolved together. So who am I, where do I stop? We have to rethink what a genome is, what a cell is, what an individual is, what a plant is, and what the ecosystem is.

How Plants Understand Each Other

When plants are attacked, they warn their neighbors so that they can defend themselves. We now know of around 2,000 scent variants that a plant needs for communication. It uses them to attract beneficial organisms or drive away attackers. In the soil, it also communicates with its microbiome or with mycorrhizal fungi. With good mixed cultures, the mycorrhizal network can be like a dynamic underground marketplace. Plants with long roots bring water, legumes offer nitrogen, phosphate-dissolving plants provide phosphates, and plants that are particularly good at photosynthesis provide sugar compounds. Are plants maybe even more dependent on communication than we humans, because they cannot simply run away?

We could say that a plant is communication—a plant is relationship. Patrick Grof-Tisza from the University of Neuchâtel even proved that desert sage has different scent dialects. If a transplanted desert sage from southern California is attacked, desert sage plants from the north cannot understand its warning signals, and vice versa. So, plants are also individuals. I was able to observe this on the way up here. [To the Evolving Science 2024 conference.] There are two magnificent maple trees. One is already bright yellow, the other still completely green. Both healthy. They react differently—they are individuals.

Communication is equally important for animals. For example, an anthill functions because of bottom-up and top-down communication. An anthill depends on innovative, experienced ants to find new strategies when the environment changes. “One of the main characteristics of life is communication—exchanging information, building social relationships, networking. This, in turn, requires learning, making decisions, acting with intention, and having goals. This also applies to ants,” said ant researcher Olga Bogatyreva.

Plants are not finely tuned automatons. They communicate, they network, they learn, they have dialects. Ants are not pre-programmed robots that just zip around, guided by a divine entity or swarm intelligence. Bacteria are not, as I learned in my studies, simply evil pathogens—we are fundamentally dependent on the entire microbiome and the bacteria. And neither a plant nor an ant nor I am alone. We are all holobionts. We live through relationships with each other and with the environment.

A plant changes. It is a constant and endless network of relationships that flows and is constantly changing. Competition and cooperation are not always distinguishable there. I’m struck by two things: How incredibly little we actually know. And on the other hand, how incredibly much are we currently destroying.

I asked a friend, a philosopher: What does identity mean? His answer: Identity is something that is not there from the beginning—you acquire it through socialization. And it also changes. I have a different identity today than I did 40 years ago. Identity is something that flows, or as Heraclitus says: “We never step in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and we not the same human being.” He also said Panta Rhei, “everything flows.” So I, or the desert sage or the ant, always remain the same living being, but we are also always different because the world is constantly changing. Communication and building relationships are the most important foundations.

This is a shortened and lightly edited version of the talk given at the conference.

More Natural Science Section: Evolving Science 2024 | Florianne Koechlin | Plant Whispers

Translation Laura Liska

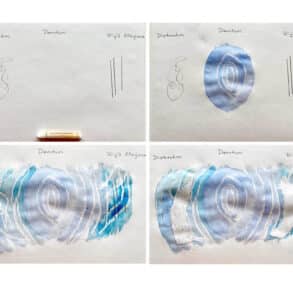

Image Diversity on Perennial Roots Farm, Photo: Stewart Lundy