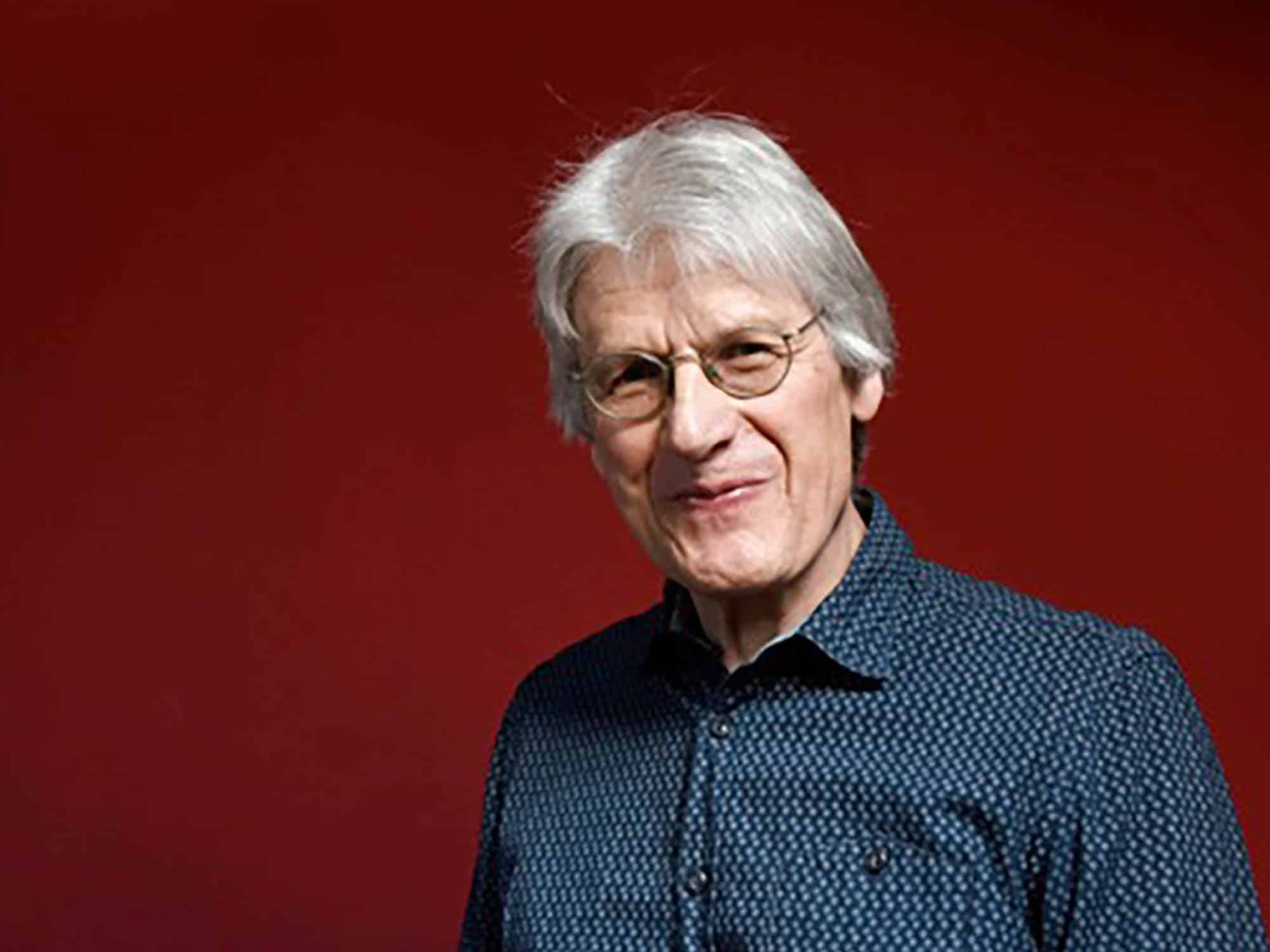

For Michael Kurtz, who crossed the threshold on April 25, 2024.

In the beginning, I was simply amazed. In 1988, a biography of the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen was published by Bärenreiter.1 The author: Michael Kurtz. I’d never heard of him. I’d studied at the Cologne University of Music, where Stockhausen taught in the late 1960s and 1970s, but there was never any talk of a Michael Kurtz. And yet, an inner voice told me, “You must read this book”—and I have not regretted it. In both biographical and technical details, Michael’s descriptions were always engaging and stimulating and, at the same time, professionally competent and instructive, without ever being patronizing or preachy. And all this in view of the highly demanding subject matter of electronic music. So I was deeply moved by Michael Kurtz’s writing as he traced the forty year historical emergence of this new type of music.

Several years later, I heard that the author was a Waldorf teacher from Bochum, Germany, who had, on various occasions, also reported about his research on contemporary music in the context of the Section for the Performing Arts at the Goetheanum. I decided to seize the opportunity and shortly thereafter, during his stays in Dornach, we spent hours talking about music but also about the visual arts and, of course, Rudolf Steiner. It was at this time, in the early 1990s, that Michael had the idea to contact contemporary composers and ask them to compose a piece that would accompany Rudolf Steiner’s chalkboard drawings as they toured renowned museums throughout the world. I was pretty skeptical at first, but when I saw Michael in conversation with the multi-award-winning Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho and later with Toshio Hosokawa (Tokyo), Frank Michael Beyer (Berlin), Eve Duncan (Melbourne) and others, I was touched and fascinated by the great respect that all these composers showed Michael Kurtz, and at the same time impressed by the light-heartedness and matter-of-factness with which they dealt with the chalkboard drawings—and so also with the contents of anthroposophy.

Master of Mediation

Michael Kurtz was a true master of mediating between these different worlds. And so some ten compositions were premiered in various museums around the world as part of the opening of exhibitions of Steiner’s chalkboard drawings. Some of them were also performed in the Carpentry Workshop at the Goetheanum, including the work “Essay 3/Steiner” for solo cello by Luca Lombardi, originally composed for the chalkboard drawing exhibition in the gallery of La Sapienza University in Rome. The theme here was “Social Threefolding,” which especially appealed to the composer. I couldn’t stop being amazed.

Michael Kurtz’s time as a Waldorf teacher, first in Ottersberg, Germany, and then as one of the founding teachers at the Widar School in Bochum-Wattenscheid, was also of great importance to him. Above all, the move to Bochum was to lead to an expansion of his musical experience as he moved closer to Jürgen Schriefer, who had taken over the leadership of the School of Uncovering the Voice [Schule der Stimmenthüllung] established by the singer Valborg Werbeck-Svärdström in 1972. Schriefer’s lectures and courses were a revelation for Michael Kurtz. At the same time, he continued to devote himself to contemporary music, held discussions with important representatives of new music, and processed all these experiences into his further publications. His biography of the Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina,2 who, together with Edison Denisov and Alfred Schnittke, formed the “musical avant-garde” in Russia, is an especially important work. His first meeting with the composer took place in 1986 and was followed by almost 80 interviews with friends, relatives, musicians, and composers in ten countries. In 2001, the biography was published in German—his chronicle ends with the Award of the Goethe Medal in Weimar (Apr. 8, 2001).

“Festival Days” in Dornach

When the knowledgeable, deeply moving biography of Karlheinz Stockhausen was published, Michael Kurtz was already on his way to Dornach to give music the place it deserves within the framework of the Section for the Performing Arts at the Goetheanum. In numerous conferences, symposia, festival events, and concerts, he gave a voice to Rudolf Steiner’s musical impulse and also to numerous musicians who have intensively engaged with this work. At the same time, Michael sought a dialog with contemporary music and staged “Festival Days” at the Goetheanum with works by Sofia Gubaidulina, who even attended the event herself.

What Makes Our Existence Substantial

But, Michael Kurtz’s most important work is probably his nearly 600-page study Rudolf Steiner und die Musik: Biografisches, Geisteswissenschaftliche Forschung, Zukunftsimpulse [Rudolf Steiner and music: biographical, spiritual-scientific research, impulses for the future].3 The starting point was the publication of issue no. 26 of Nachrichten der Rudolf Steiner Nachlassverwaltung [News from the Rudolf Steiner estate administration] (later, Beiträge zur Rudolf Steiner Gesamtausgabe [Contributions to Rudolf Steiner’ Complete Works]) in 1969 under the title “Wortlaute von Rudolf Steiner über Musik” [Words from Rudolf Steiner about music] edited by Helmut von Wartburg, music teacher at the Rudolf Steiner School in Zurich.4 As Michael Kurtz had repeatedly come across passages relating to music in Rudolf Steiner’s lectures that were not included in von Wartburg’s overview, he finally approached the archive to ask whether an expanded new edition would be published in the foreseeable future. Unfortunately, we archivists had to say no, but this triggered intensive research and a lively exchange about further sources. At that time, Michael Kurtz deepened his biographical studies on Rudolf Steiner and music: Steiner and Anton Bruckner, Steiner and Richard Wagner, Steiner and Nietzsche. Kurtz paints a picture here that could not be more colorful and exciting. One of the highlights is Chapter V: “Rudolf Steiners Mysteriendramen als Gesamtkunstwerk und drei Werkutopien von Arnold Schönberg, Alexander Skrjabin, und Charles Ives” [Rudolf Steiner’s Mystery Dramas as a total-work-of-art and three utopian works by Arnold Schoenberg, Alexander Scriabin, and Charles Ives]. Such a chapter title does not simply fall from the sky but is the result of listening and devotion to that which makes our existence substantial. It has indeed become an astounding book that teaches us many things, but above all, it teaches us to be amazed.

On April 25, 2024, Michael Kurtz took his leave of Earth after a short, severe illness. Still, the connection remains because, according to Rudolf Steiner (in the Kassel lecture of May 10, 1914): “Those who have passed through the gate of death look at me; they enliven me; they are with me; their forces radiate down upon me.”5—I’m looking forward to that. Thank you, dear Michael! Walter Kugler

A Thank You to Michael Kurtz, 1948–2024

“We human beings of the present need the right hearing for the morning call of the spirit!” Michael Kurtz courageously led the way in not being afraid of new sounds. Time and again, he gave us hope, encouragement, and courageous implementation.

In 1993, the Goetheanum published a 40-page supplement by Michael Kurtz on “Music in the second half of the century” [Musik der zweiten Jahrhunderthälfte].6 Three questions were put to important living musicians. This breviary had an impact, drew attention, uncovered something, and had a powerful effect. This “supplement” significantly exhibited decades of faithful engagement with and indications of current musical developments, testifying to Michael Kurtz’s pedagogical and enlightening ethos.

Always acting against the background that Rudolf Steiner’s indications regarding such questions were also at hand, Michael Kurtz was one of the few who handled these indications in such an extremely integrated way that all the while, was open to the future. Others used them to form “Berlin Walls” in the face of any development beyond Bruckner and ideologically hid themselves within. This latter approach led to a complete alienation between the events of contemporary music and the majority of artists and composers based on Rudolf Steiner. Michael Kurtz, on the other hand, acted as a mercurial mediator and defender of the important future-oriented impulse, namely, by listening to the musical morning calls to us human beings of the present.

In his crucial publications on Stockhausen (1988),[1] Gubaidulina (2001),[2] Saariaho, Hosokawa, and many others,7 Michael Kurtz has set incisive accents for the times. With his 600-page work on Rudolf Steiner und die Musik [Rudolf Steiner and Music],[3] he put his foot in the door in terms of rescuing and rehabilitating the fascinating seeds of an open future in musical development. What in most other cases turned into a rather reactionary and restorative appropriation, Michael Kurtz countered in a sympathetic tone and set the record straight, opened it up, preparing Rudolf Steiner’s musical impulses for future generations as living, germinating ideas. We owe Michael Kurtz many an eye- and ear-opener in musical matters. For the anthroposophically oriented artists, who indeed move primarily in the pictorial and imaginative and are content with that, he has decidedly dared to take the step into the uncomfortable, ever-moving musical and inspirational and thereby built a gateway for the future and of the future.

It is with great gratitude that I pay tribute to Michael Kurtz, express my high esteem, and salute him in the spiritual world. May his milestones continue to inspire, encourage, and open the eyes and ears of future generations! Stephan Ronner

More See Rudolf Steiner, Music: Mystery, Art, and the Human Being, edited and introduced by Michael Kurtz (Forest Row, East Sussex: Rudolf Steiner Press, 2016).

Translation Joshua Kelberman

Photo: Michael Kurtz; Photo Credit: Anna Krygier

Footnotes

- Micheal Kurtz, Stockhausen: A Biography: (London: Faber and Faber, 1992); first published as Stockhausen: Eine Biographie (Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1988).

- Michael Kurtz, Sofia Gubaidulina: A Biography (Bloomington, IN: Indiana Univ. Press, 2007); first published as Sofia Gubaidulina: Eine Biographie (Stuttgart: Urachhaus, 2001).

- Michael Kurtz, Rudolf Steiner und die Musik: Biografisches, Geisteswissenschaftliche Forschung, Zukunftsimpulse [Rudolf Steiner and music: biographical, spiritual-scientific research, impulses for the future] (Dornach: Verlag am Goetheanum, 2015).

- Helmut von Wartburg, ed., “Wortlaute von Rudolf Steiner über Musik” [Words from Rudolf Steiner about Music] in Nachrichten der Rudolf Steiner Nachlassverwaltung [News from the Rudolf Steiner estate administration], no. 26 (Summer 1969): 6–34.

- Rudolf Steiner, Our Dead: Memorial, Funeral, and Cremation Addresses 1906–1924, CW 261 (Hudson, NY: SteinerBooks, 2011), includes a lecture in Kassel on May 10, 1914.

- Michael Kurtz, “Musik der zweiten Jahrhunderthälfte: Darstellungen, Fragen und ein Blick auf die Entwicklung durch das 20. Jahrhundert.” [Music in the second half of the century: presentations, questions and a look at the development through the 20th century], Das Goetheanum 72, no. 50, Musikbeilage [Music supplement] (1993).

- See, among others, Michael Kurtz, “Kaija Saariaho: Synästhetische Wahrnehmungen” [Kaija Saariaho: synaesthetic perceptions], Die Drei 76, no. 6 (2006); “Toshio Hosokawa: Ein japanischer Komponist zwischen Ost und West” [Toshio Hosokawa: A Japanese composer between East and West], Die Drei 73, no. 3 (2003); “’Und diese Tiefe der Zeit möchte ich erreichen.’ Ost-West-Musik- und Kulturfesttage Interview mit Toshio Hosokawa” [“And I want to reach this depth of Time.” East-West music and culture festival onterview with Toshio Hosokawa], Das Goetheanum 81, no. 5 (2002).

Thank you for this nice little gem of an essay.

While I haven’t read Kurtz’ biography of Stockhausen, I share the authors’ observation of the split that exists between contemporary art music on the one hand and anthroposophically-oriented music on the other. The former tends to shun away from anything spiritual while the latter is often not open to anything new (e.g. electronic music). Stockhausen, like Steiner, was highly sensitive to spiritual realities, and while Steiner gave them presence mostly in his words, Stockhausen let them resonate in his music. I hope that the efforts of Kurtz and of the authors as well as my own efforts as a composer of electronic music and a writer (see for example my publication on Das Goetheanum “On Earthly and Cosmic Music”, https://dasgoetheanum.com/en/on-earthly-and-cosmic-music/) will bring people to consider these issues more attentively.

It would be very interesting to find a complete list of the works and composers that Kurtz inspired to compose based on Steiner’s chalkboard drawings. Does anyone have any more information on this project?